Great Women Artists: A Visual, Historical, and Overdue Artistic Journey

Great Women Artists, a massive yellow-tinted book, is an extensive collection of art spanning over 500 years and featuring over 400 passionate, diverse artists—and they’re all women. The artists are from over 50 countries, each with their own backgrounds, cultures, and histories, and encompass various mediums, from painting and sculpture, to photography and video installations. The collection promotes art created by every type of woman, and reflects on an era when art made by women, for women, is more prominent than ever. ” Great Women Artists is the most extensive fully illustrated book of women artists ever published,” said Laurent Claquin, head of Kering Americas. “I think that’s very exciting. It also holds great significance and inspiration for women in the arts today.” The cover of the book suggests a strike through the word “women”— hinting at the lack of appreciation for art created by women and its impact across history. The title was a deliberate choice and an immediate response to an essay by art historian, Linda Nochlin, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists.” In her essay, the art historian delivers an extensive look into female creativity throughout time and how it is still influential today. Much like this mesmerizing compilation of art by great artists, the essay uplifts and glorifies women who’ve been under-appreciated and undervalued for way too long by the art world. Below are a few of the works and incredible artists featured in Great Women Artists. In the words of Pat Steir, “What makes a great artist? Great art….”

———

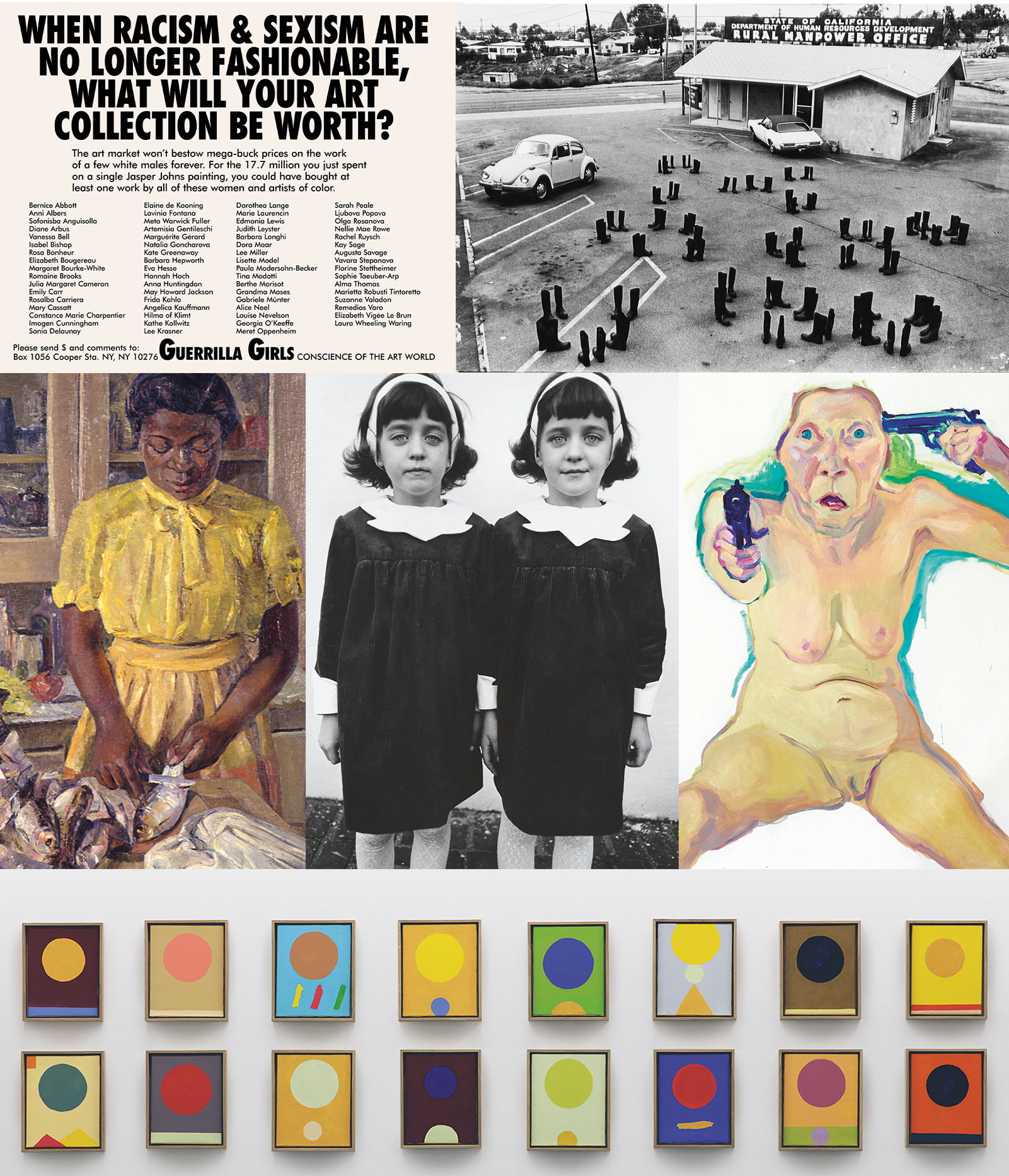

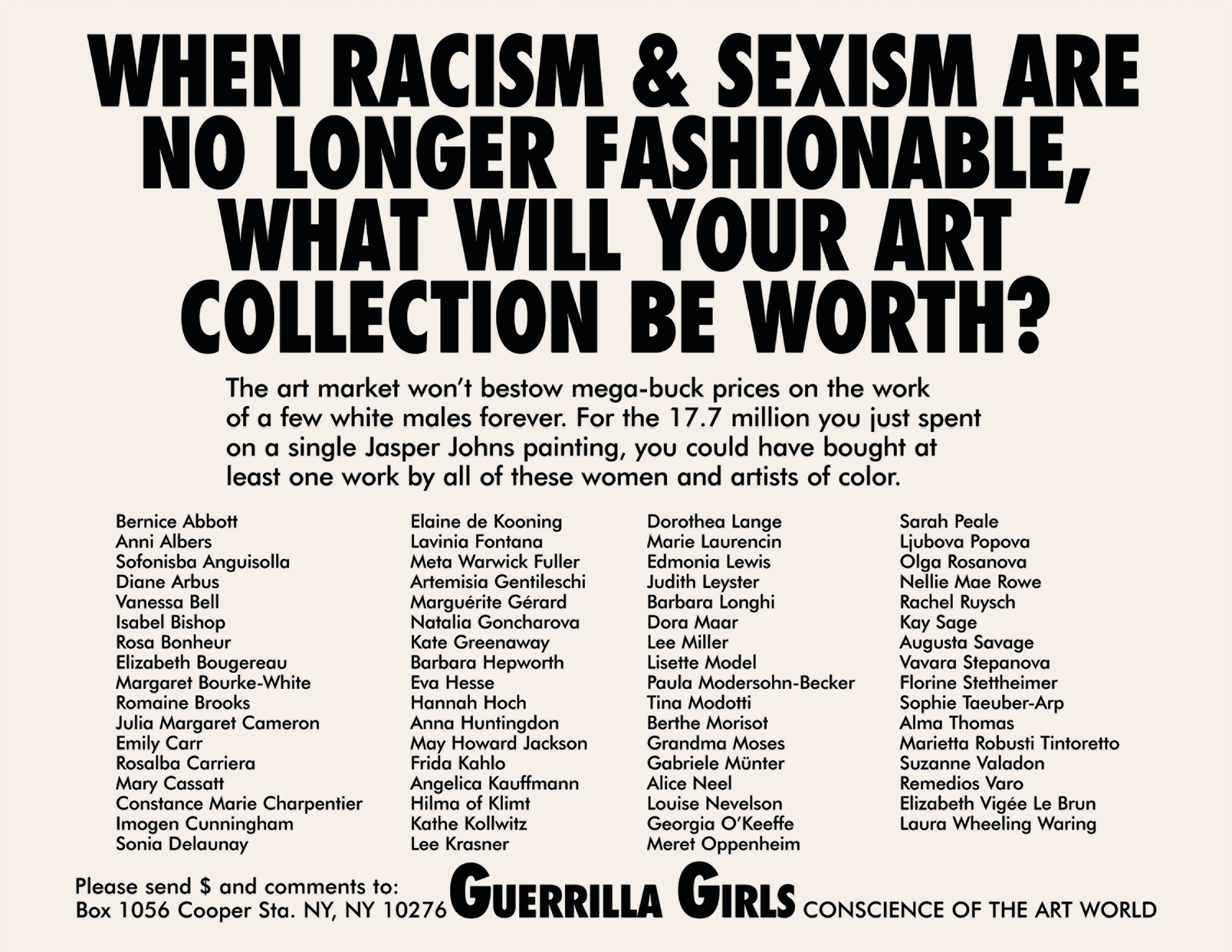

When Racism And Sexism Are No Longer Fashionable, What Will Your Art Collection Be Worth? by Guerrilla Girls, 1989

Guerrilla Girls (active from 1985), When Racism & Sexism Are No Longer Fashionable, What Will Your Art Collection Be Worth? 1989, offset lithograph on paper, 43.2 × 55.9 cm (17 × 22 in). Picture credit: © Guerrilla Girls. Courtesy guerrillagirls.com. (page 165)

The Guerrilla Girls are a group of women and art activists who use historic women’s artists names and masks to stay anonymous, working to expose sexual and racial discrimination in the art world. The group originated in 1985, after protesting at New York’s Museum of Modern Art exhibition An International Survey of Recent Painting and Sculpture, for their lack of representation of women and people of color. There most recognizable work, titled Do Women Have to be Naked to Get into the Met Museum? features the work of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, in which they applied their famous mask to an image of a nude woman in La Grande Odalisque. Under the image is a statistic, “Less than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female.”

———

Du Oder Ich (You Or Me) by Maria Lassnig, 2005

Maria Lassnig (born 1919, Kappel am Krappfeld, Austria, died 2014, Vienna), Du Oder Ich (You Or Me), 2005, oil on canvas, 203 × 155 cm (79 ⅞ × 61 in), private collection. Picture credit: © Maria Lassnig Foundation, Courtesy Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Stefan Altenburger Photography Zürich (page 232)

This self-portrait features Maria Lassnig’s method of “body-awareness-painting” a term she coined when painting bodies and ‘”external realities” in an effort to paint bodily sensations. With a combination of terror, horror, and vulnerability, this piece challenges the representation and use of the nude female body in art. At the time of this painting, Lassnig had been professionally painting for over 70 years, although largely unrecognized until later in her life. She lived and painted in various places, including Paris and New York, only to return to her home of Vienna, Austria to teach at the University of Applied Arts.

———

Jennie by Loïs Mailou Jones, 1943

Loïs Mailou Jones (born 1905, Boston, died 1998, Washington DC), Jennie 1943, oil on canvas, 90.8 × 73 cm (35 ¾ × 28 ¾ in), Howard University Gallery of Art, Washington DC. Picture credit: Courtesy of Loïs Mailou Jones Pierre-Noel Trust. (page 204)

Loïs Mailou Jones began her career as a textile designer in Boston in the 1920’s, but became involved in the fine arts after studying at Boston’s School of the Museum of Fine Arts and eventually, Howard University. In 1937, Jones left for Paris to study painting at The Académie Julian, in which she introduced African motifs into her work, and found France to be much more “racially tolerant” than America at the time. Her subjects were some of the first paintings by an African-American artist to extend beyond portraiture. Upon returning to the U.S., Jones met Alain Locke, esteemed philosopher and leading figure of the Harlem Renaissance. Locke encouraged the artist to concentrate on black subjects, much like the piece above, influenced by African and Caribbean culture.

———

The Weight Of The World 1–20 by Etel Adnan, 2016

Etel Adnan (born 1925, Beirut), The Weight Of The World 1–20, 2016, oil on canvas, each 30 × 24 cm (11 ¾ × 9 ½ in), installation view, ‘Etel Adnan: The Weight of the World’, Serpentine Sackler Gallery, London, 2016. Picture credit: © the artist / Courtesy Galerie Lelong, Paris. Photo © Jerry Hardman-Jones. (pages 22-23)

The Lebanese-American artist Etel Adnan is known internationally for her poetry, prose, and essays. Her writing incorporates surrealist imagery, and addresses political, social, and gender-based injustice. Adnan moved to Paris in 1977 after the Lebanese civil war began, where she wrote the novel Sitt Marie Rose, which won the France-Pays Arabes Award. Her art is inspired by the natural world, as well as by her own experiences and culture. The Weight of the World features 20 canvases, all in different sizes, shapes, and colors, which she created when she was 91-years-old.

———

Identical Twins by Diane Arbus, 1966

Diane Arbus (born Diane Nemerov, 1923, New York, died 1971, New York), Identical Twins, Roselle, N.J., 1966, 1966, printed between 1967 and 1970, gelatin-silver print, image, sheet and aluminum mount, 36.2 × 36.2 cm (14 ¼ × 14 ¼ in). Picture credit: © The estate of Diane Arbus (page 39)

Diane Arbus got her first camera in 1941. After studying for quite some time, she became “fascinated by the uncanny within the every day.” Throughout her career, she photographed nudists, circus performers, giants, and of course, identical twins. In the photo above, the twins are seen shoulder-to-shoulder against a white wall, riffing off the “mystical and psychic connection” between identical twins.

———

100 Boots Looking For a Job, San Clemente, California by Eleanor Antin, 1972

Eleanor Antin (born Eleanor Fineman, 1935, New York), 100 Boots Looking For a Job, San Clemente, California, 1972, vintage gelatin silver print mounted on board, 31.8 × 47.8 cm (12 ½ × 18 ¾ in). Picture credit: © the Artist. Courtesy of Richard Saltoun Gallery (page 36)

Antin moved to San Diego in 1969, where she explored themes of identity, feminism, and history in her photos and films. Antin often used props in her work to suggest human presence, like the photo above, in which she took 100 black rubber boots across the country for over two years, photographing the props doing everyday tasks along the way. After questioning the essence of the artwork, the photos were finally exhibited in 1973, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, alongside the black boots. She produced 51 photographs in total.

———