Brad Ogbonna

I think of the “art world” as sectioned off. The term triggers an imaginary place with high-walls, glass ceilings, and the impossibility of citizenship. I can recognize that this world is an imaginary construct—a figment of my mind. When I look at the word “art” in and of itself, the scope feels infinitely expansive and immediately engaging. And so I’m here, partially writing about art—but also partially testing the strength of its world’s borders.

In the normal world, I have no business writing about visual art. My discipline is music. I make music professionally and when I read about art—music included—and witness how people engage in writing about art, it only seems to deepen the divide between those in the know and everyone else. The traditional art world narrative reinforces the age-old myth that writers have specialized knowledge and that art is a far removed thing to behold. But I’m writing for the same reason I make music. As I see it, everything is art and specialized knowledge is unimportant.

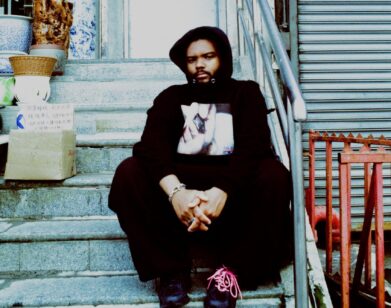

Recently, I spoke with Brad Ogbonna, a self-trained, Nigerian-American photographer who has worked with the likes of Adidas, The FADER, and the painter Kehinde Wiley. It was a conversation to learn and share Brad’s story, but also to help me figure out where I stand in proximity to him and his work.

I feel a closeness to Brad. He is a visual artist from Minnesota who lives in New York City. I am a sound and recording artist from New York City, living in Minnesota. He and I met via social media some years ago. Since then, we’ve maintained an ongoing conversation about art, music, politics, location, duality, and our respective disciplines. We are co-disciples, often studying the same cultural topics and openly sharing opinions and ideas.

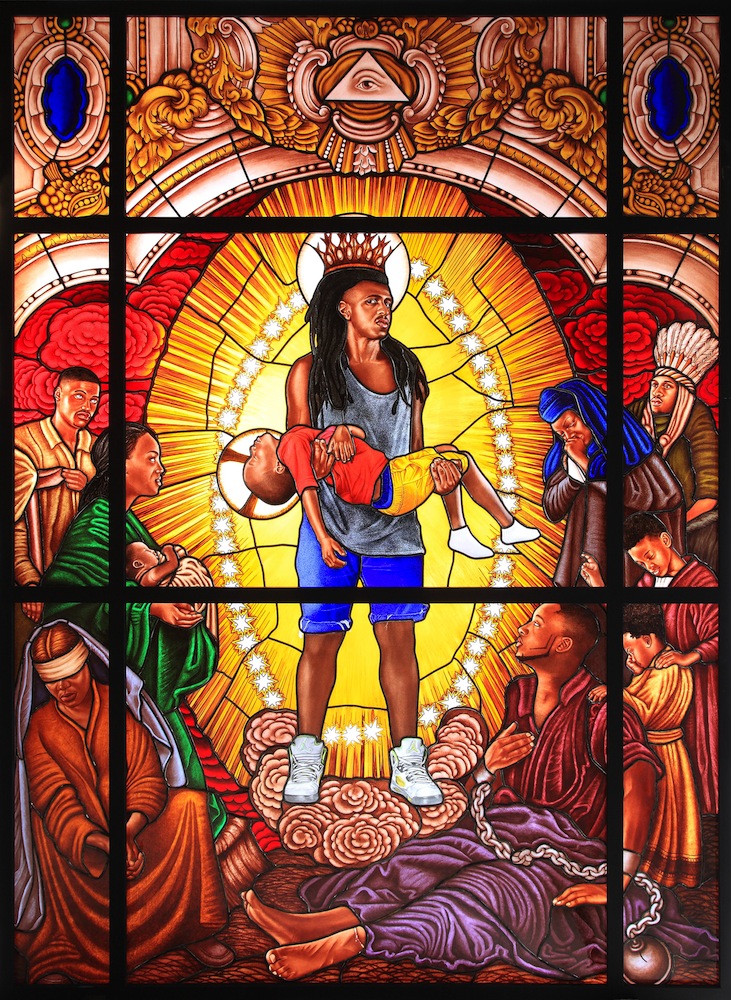

This fall an image of Brad Ogbonna appeared in my feed. It featured Brad in vibrant Dutch-wax rich colors, wearing a golden crown, denim cut-offs, and a pair of Jordans, painted in the characteristic workmanship of Kehinde Wiley. Flocked by a community of lamenting, black-skinned onlookers, Brad stood tall with a young, limp, black body lying horizontally across his arms.

Stained into a glass window in the style of a European gothic cathedral, this rendering is one of 10 images in “Lamentation,” Wiley’s first solo show in Paris at the Petite Palais. It borrows iconic signifiers of minted U.S. dollar notes, complete with the Eye of Providence, Native American feathers, circular seal shapes, and a representation of Themis (the blindfolded Greek goddess of Justice). The juxtaposing imagery makes a compelling narrative on capitalism, values and the worth of black lives; a wiley take on black lives matter. As a whole, the exhibition feels like an overdue coronation of a man who has been art royalty for many years and, in turn, a personal coronation for Brad.

WILL JOHNSON: I’m thinking of the silent, nameless black models in the Dutch “old master” paintings and here we are, 2016. How does it feel to be involved in a major art exhibit by a major contemporary artist?

BRAD OGBONNA: It’s really exciting. It just feels timeless and it’s not something that’s been done before on this level. I feel like a Paris museum is thought of as the upper echelon of what’s considered the art world. And then, having a Nigerian who’s from South Central, L.A., is huge and just the subject matter … I’m wearing a crown adorning a French museum façade. That’s pretty crazy. It’s something I’m proud to be a part of.

JOHNSON: Could you tell me the story of how you met Kehinde and also how you got approached to be a subject in “Lamentation”?

OGBONNA: I got introduced to Kehinde via a friend of mine who works with his studio. He mentioned that they were looking for a media guy to work on photo stuff and video projects. He told me all this at a party, so it was sort of like, “Okay, yeah. Sure.” Then I heard back from Kehinde’s manager, and she told me that Kehinde saw my work and that he liked it and I should come by Brooklyn Museum to meet him and take some photos of behind the scenes stuff. I did that, met him briefly—for maybe less than two minutes—and took photos and was part of that whole experience at the museum. A week later, after not hearing back, I got a call out of nowhere: “Do you have a passport? Are you able to travel for a project?” That was our first project together. We’ve done a couple international trips and whenever he feels inspired, he’ll call me and ask me to come in. It’s a real arbitrary thing; just get a call—”let’s work”—whenever.

JOHNSON: Word. How does that turn into you becoming a model for one of his paintings?

OGBONNA: I’d been working with him for a year and a half as a photographer and he mentioned something like how I never really have a mustache. I was like, “Yeah, I don’t really grow facial hair like that,” and he said, “Well, the moment you grow facial hair, I’ll put you in a painting.” I just laughed it off; I still wasn’t in a rush to grow a mustache. For me, I need seven to 10 days of solitude to grow a mustache peacefully without looking crazy. But then I finally grew one and he was like, “Perfect.” We were shooting a project and we had a couple kids by in the studio—couple of guys—and they threw me in it. I was there working, but they asked me to jump in for that.

JOHNSON: When you say you work with Kehinde as a photographer, what does that mean exactly?

OGBONNA: It’s his vision. When I’m working with him, it’s really more of me helping to bring his idea and his mood to life. He has a very specific way of doing things, so working with him as a photographer is a big part learning his language and how to take photographs with specific lighting and shadows and highlights that will translate to his painting.

JOHNSON: You’re a photographer and you’re used to being behind the camera. Then, all of a sudden, for this piece, you’re front-and-center of the camera and the image. One thing that’s really dope to me is that, in Kehinde using you as a model for his work, there’s this conversation about subject, object, and gaze. It almost feels like he’s projecting his own artistry onto your artistry—the artist as the art. It made me curious about how you feel being behind the camera and how you see your approach as similar or different than Kehinde’s?

OGBONNA: For me, when I approach it, it’s like I’m catching people at all stages—their most vulnerable, their most dark, their most happy … I’m not one to place much direction on people too often. I feel like for him, he’s shooting from a very specific angle, literally and figuratively. The way we shoot a person is always specific and intentional. We’re really mindful of angles—photographing to capture the most regal, strong, and proud parts. We’re not catching people at their most vulnerable, and that always feels intentional because a lot of the people in his imagery are coming from the margins. The work is about the strength of these people. My work is different in that it’s showing different sides of that. But I guess that was more so before I met him. I was showing the vulnerable, the human nature of people for personal work, but now I feel like the way I shoot people has changed a little bit. He’s had an influence on the way I think about direction and position.

JOHNSON: You feel like you can be more mindful of how the body language of proud vs. vulnerable reads in imagery?

OGBONNA: Right. exactly.

JOHNSON: How do you think of a Brad Ogbonna photograph? What visual language is at work?

OGBONNA: I want it to feel real—genuine, not too contrived. I try to get real emotions out of people and real experiences. I try not to dress it up too much. I’m not someone who’s going to be on Photoshop all day.

JOHNSON: Looking at the images where you’re modeling as a subject vs. the images that you’ve taken as a photographer, I feel like there’s no point in distinguishing the difference between being a photographer and just being a human who’s trying to live artistically. When I think about your work, you have a really specific style. I think about this with music; most of what I focus on when I’m making music is just what my unique experience is and making sure I’m true to that. That’s all that style is. If I’m being aware of that, it’s going to come across no matter if I’m being a musician, a writer, a visual artist, a brother, a boyfriend, when I’m cooking dinner, whatever … it’s all the same thing for me.

OGBONNA: Definitely. I don’t have any formal training in photography so everything is self-taught. I’m just a product of the internet. Looking shit up, being inspired by what my peers are up to on the internet. I feel like there’s no real rules to things. When I think of Kehinde, I don’t think of him as a painter anymore, I think of him as a multi-disciplinary artist. He does all kinds of things—videos, photography… I get to see him as a painter mostly because I see him paint all the time, but it’s a bigger idea.

JOHNSON: It’s funny, because when I think of his work, if you’re focusing too much on the painting, you’re missing a lot of other stuff that’s happening. The first piece I saw was the Napoleon [Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps, 2005] piece at Brooklyn Museum. It was me and my homeboy Ahmad from the Bronx—and he’s a dude that loves art and cares about art, but is maybe not specifically invested in “fine art.” We would go to the Brooklyn Museum and be finding new things in that piece every time we saw it. For me, there’s always a conversation about black male intimacy in his work and connecting communities. I’m always curious about the subjects of his paintings—like, what is the Napoleon dude up to these days?

OGBONNA: [laughs] I can’t say, but just from the time I’ve been working with him in the last year or two, a lot of projects that he’s been doing in the last 10 years, he’s still in contact with these same people. Even a lot of the people from the stained glass window project, they’d been in his other paintings, like, eight years ago. There’s a couple people from this video—Smile—we redid it this past year and we still had people from the original video come back, so that was cool to see. I think of Kehinde as a real gateway, a bridge, a connector for so many people—people of color especially—who are often shunned from the opportunity to view and identify themselves in modern art.

JOHNSON: It almost seems like working with Kehinde could be a weird form of learning the business art and the art world as well. You’re not just learning about lighting, shading, and color theory, but also the trade of the art business, and that there’s actually a really cut-and-dry way to be successful. Has your perspective changed about this?

OGBONNA: Prior to working with him, I knew nothing about the art world or like galleries or museums or how that world moves in general. The fine art side of photography, I wasn’t accustomed to that. So I’ve seen him and seen how work is made and purchased and distributed and all the moving pieces of it—that does seems like a different school of thought.

JOHNSON: Does that world seem more intimidating now or less?

OGBONNA: I guess it seems less so because, when I’m ready to jump into that world, now I know that world is not that closed off.

JOHNSON: Or at least you know how the gates look. [laughs]

OGBONNA: And that there’s no rules.

WILL JOHNSON IS A MINNESOTA-BASED MUSICIAN AND SOUND ARTIST WHO CURRENTLY RECORDS UNDER THE NAME WILLS. KEHINDE WILEY’S “LAMENTATION” IS ON VIEW AT THE PETIT PALAIS IN PARIS THROUGH JANUARY 15, 2017. FOR MORE ON BRAG OGBONNA’S WORK, VISIT HIS WEBSITE.