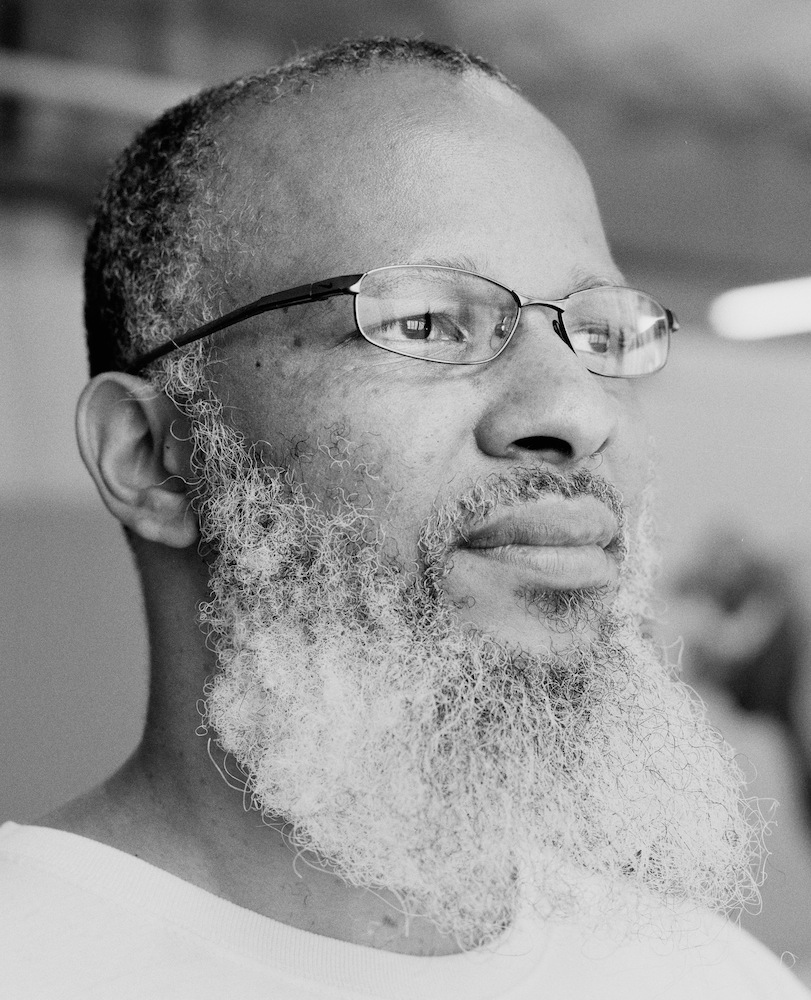

Artists at Work: Meleko Mokgosi

MELEKO MOKGOSI IN BROOKLYN, NEW YORK, AUGUST 2016. PHOTOS: MARK DAVIS.

This summer, during group shows and ahead of fall exhibition openings, we’re visiting New York-based artists in their studios.

Meleko Mokgosi paints his subjects at just above life size. It’s an artistic sleight of hand that makes the figures seem poised to step off the canvas and into the room—or, rather, float off into space. His paintings take on a dream-like quality: they are meticulously rendered, fragmentary (some appear unfinished), imbued with magic and portent, and full of symbols, animals, faces obscured by darkness.

Mokgosi is less interested in dreams, though, than he is in looking to the past. He was born in Botswana in 1981 and moved to the United States to study art at Williams College. He received an MFA from UCLA in the Interdisciplinary Studio program, and now teaches full-time at New York University. Though he claims that he is “no academic, just a painter,” he combs through the past like a historian, looking to form a clearer picture of the present. A voracious collector and reader (of topics like postcolonial and gender theory), it is only after months of research that his brush touches the canvas. And when it does, everything is brought into dazzlingly high relief.

In September, Jack Shainman Gallery will present Mokgosi’s first solo show in New York at both of its Chelsea locations. The show focuses on two chapters of an ongoing project that Mokgosi calls “Democratic Intuition.” Its first iteration was shown in 2015 at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston.

MATT MULLEN: It’s less than a month until your show. How have you been feeling?

MELEKO MOKGOSI: It’s really terrifying. I’ve been living here for five years, but this is my first New York solo exhibition.

MULLEN: That’s a big deal!

MOKGOSI: Some would say so. You know, New York bills itself as the cultural capital. Obviously we know that’s not true, but we still feel it. So I’m nervous. I’ve been here for a while. It’s where my institution [NYU] is. It’s like sharing your backyard. I think the most important thing for me is if one or two people can see what I’m trying to do and find the ideas interesting, then I’ll be happy.

MULLEN: Can you tell me about those ideas?

MOKGOSI: This project began in 2014. It’s called “Democratic Intuition.” My previous project was about the idea of nationalism; it was basically trying to understand things like xenophobia. Things like why people, at a certain time or period, become so nationalistic. I tried to really pose these questions but not come up with any big theory or answers. It just came from this place of, “What is going on? I can’t understand this.” And after that project I was stuck. I thought, “What the hell am I going to do?” Slowly I started thinking about democracy. How can we—without majorly philosophizing it and making it an academic thing—how do ordinary people understand this thing of democracy? How do we have access to it? Who has access to it and who doesn’t? That also came through [Indian scholar] Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s work and how she’s trying to understand democracy. She’s a superstar intellectual and the first person to translate Derrida into English, actually. So she’s kind of a big theory person—a theorist, a feminist. And at the same time, Axel Honneth, who’s a German theorist, he also wrote a book on the idea of democracy. I’m always looking at theory and history.

At its most basic, the project is about how do normal people understand, reciprocate, have access to, and not have access to the ideas of democracy and the democratic … I’m thinking about things like education, things like gender, sexuality, ethnicity, nationality. And even just the nation state—who has access to the nation state and who doesn’t? If you’re an illegal immigrant and you live in New York, you don’t have access to the state. You don’t know how to use the state. You can’t vote. And that means already that you’re outside of understanding of the democratic, right? That’s long-winded, but that’s basically it.

MULLEN: What I like is that it ultimately all goes back to this really simple idea, or seemingly simple idea: democracy. It’s accessible.

MOKGOSI: I hope so! I’m not interested in making it into some academic nonsense, but instead bring in things like love, things like emotion, progress, and group identity. My challenge is how to, in a not so cliché way, represent the complexities and complications of the idea of love.

MULLEN: That’s even more ambitious than tackling democracy.

MOKGOSI: [laughs] Right—especially if you’re from Southern Africa. You think of all the cliché and stereotypical ways that love is represented in relation to the African continent and, oh my god. So I’ve been thinking about this for a while, researching it.

MULLEN: What is your research process like?

MOKGOSI: All the stuff I’ve been talking about is the research phase, where I spend as long as I can—anywhere between a year or year and a half or eight months—just reading and researching, trying to think things through. And I travel; I go to Botswana and I take a lot of pictures. That, for me, is definitely research: going somewhere, looking, and spending a lot of time trying to figure out what I want to do aesthetically. I also go through a lot of publications, a lot of magazines, a lot of newspapers. I used to collect music. And I would collect sand samples, because the sand is so, so particular. Some sand that has clay in it that is red, but some sand is very grayish. Some sand is obviously yellowish. But then I was like, “You know what, I can’t keep smuggling sand into the country.” And it’s heavy. So, the research this time around was really trying to give myself enough time and space to think, to read, to look, to listen, to speak to people. And really just understand—or try, as much as I can, to understand—what I think I’m trying to articulate.

For me, thinking is slow. At least good thinking is slow. So I try to take my time. And then, as I’m doing it, I actually create the paintings titles. I work from the research, create the titles, and then each project so far, like this is my third one, has a title—a general title—and then I have chapters and all those chapters have titles. So this project, again, has eight chapters, and all those chapters have titles. And after those titles, I start the actual storyboard. Which, as you can see, is a series of line drawings arranged in order.

MULLEN: Going back to the idea of democracy and nationalism, I have to ask about the current U.S. presidential election. Has that been informing your work at all? Even in a more abstract way, like tapping into some sort of energy?

MOKGOSI: I don’t know. I mean, it’s hard for it to inform the paintings because all of them come from the storyboard. And like I said, once the storyboard is done, I am not going to change it, because what I try to do is build safeguards. As artists, as human beings, you live, you experience things, you’re affected by things, and sometimes we feel very strongly about something and it affects the work. But I don’t want to let it affect it, because it’s too reactionary. So if I’m going to take a year to research this stuff, and I take six months to do the storyboard, and it takes, like, another year to paint the thing … I don’t want to compromise the decisions I made a year ago with something that’s happening in this moment. I think that’s what makes me a very boring artist, because my work, I try to distance it, so that it doesn’t get too affected by the contemporary, because I’m dealing with other questions about history, about postcolonial theory, about xenophobia, about race. I try not to let it get tied too much into the contemporary.

MULLEN: Let’s turn to the paintings. The first thing that strikes me about them is their scale. They’re so big.

MOKGOSI: These are still small!

MULLEN: Well, true! They’re not even that big. But something about them … I don’t know if it’s the use of space or the shapes of the canvas, but they suck the energy of the room right into them. Can you talk about why you gravitate towards bigger canvasses?

MOKGOSI: When I first started to think about these questions of history and so forth, I settled on the ideas of history painting and also the cinematic. They fit perfectly together, mostly because history painting began as kind of the grand European genre of championing the nation state. Using this format, using this method, is a way to kind of unsettle what is going into this system of representation.

I have also been taught to understand that in art, two things become really important: the material and the scale. The materiality and scale, as you just showed, position how the viewer has the first emotional response. How do you, as a human being, respond to an object in space? That has everything to do with scale and material. So, as artists, that’s one of the first things in the equation. To do things that are always at life-size or just above life-size, it’s important to me. It gives the viewer and the painting a one-to-one relation.

MULLEN: The figures seem so alive, is that why?

MOKGOSI: Yes, but also it’s because I don’t use a white ground. Usually how you’re trained in painting is to have three to five layers of gesso, and then you sand in between layers. It gives the painting luminosity, but—more importantly—it gives you room for error. Because you can paint over things. But I don’t do that; if I screw it up, the painting is done. You know, I can’t paint over it.

MULLEN: Why not give yourself the room for error?

MOKGOSI: It’s a level of commitment. It’s not to show that I know how to paint, but to say, this is the commitment to this representation, or this thing. It takes a certain amount of time and energy and looking and resources, and understanding. But the viewer can see decisions came first and which came last. So what if I did screw that up?

Anyway, back to the figures. When you’re painting skin tone, there’s a big difference between white skin and black skin, obviously. Black skin really depends on shadows and white skin depends on layering of highlights. So I’ve found using this surface is the best surface to render black skin. But the way it has to be done, it’s reductive. I put paint on and then I remove it, to build volume. It’s important to me because ultimately, this is what I am interested in painting: black skin.

FOR MORE ON MELEKO MOKGOSI, VISIT HIS WEBSITE. HIS SOLO SHOW AT JACK SHAINMAN GALLERY OPENS ON SEPTEMBER 8, 2016.