OPENING

Artist Amy Bravo Takes Us Inside Her Cabinet of Curios

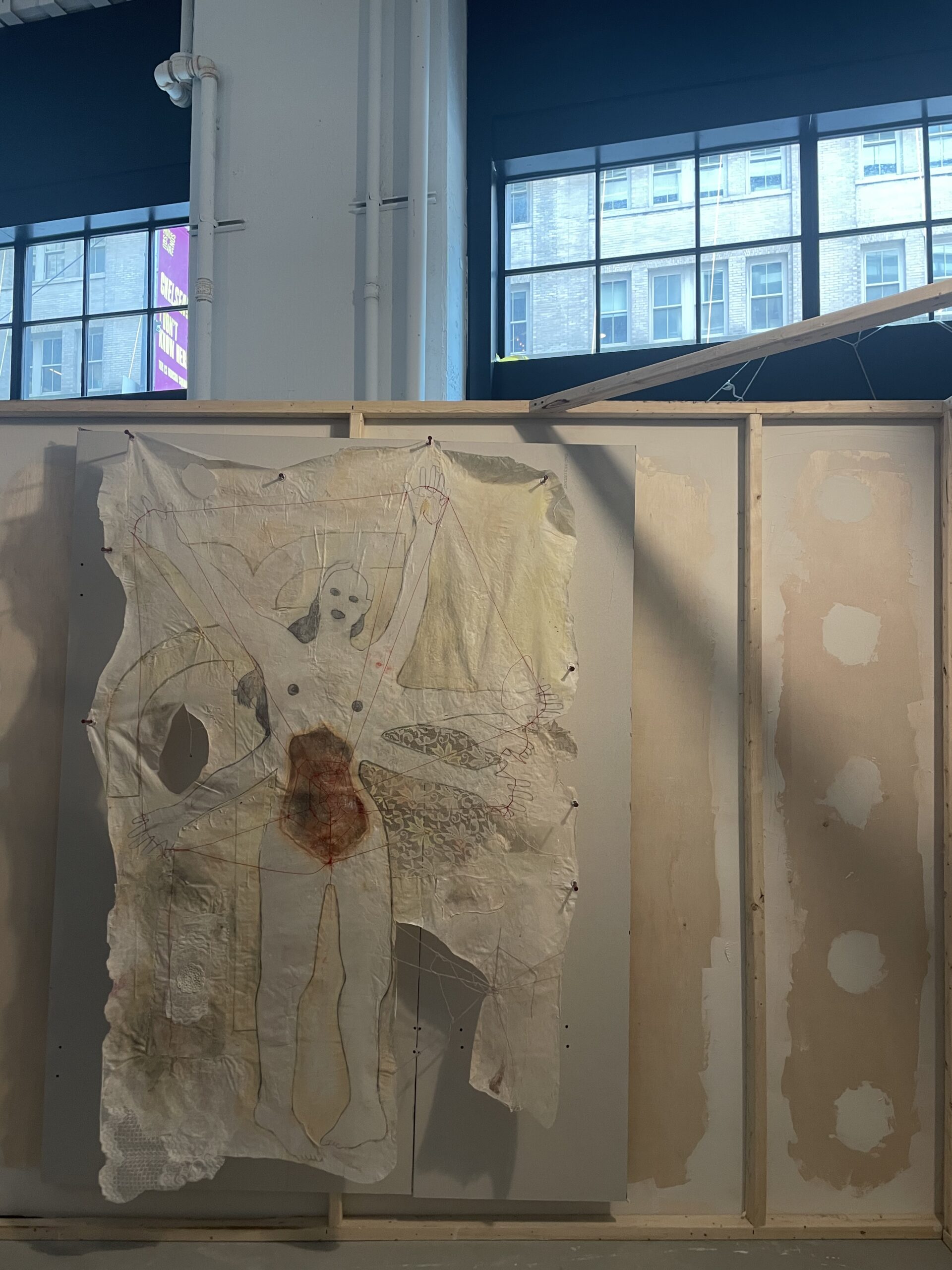

“Every artist is a collector,” Amy Bravo remarks as she points to a curio cabinet replete with boxing gloves, synthetic hair, cow bones, and a palm tree. For her solo show TransmogrificationNOW!, now on view at Swivel Gallery’s temporary new Tribeca location, the Brooklyn-based, Italian-Cuban artist flexes a rich, visceral language that repurposes family keepsakes and found objects to create a world that reflects her own family mythology and queer experiences. “I’m more interested in pulling the cracks of the family history open and creating something new inside of it” she said. Ahead of the opening, we caught up with Bravo to chat about how her mother crocheted spider webs for her show, the reality TV shows she binges while working, and a secret society of queer Cubans.

———

LILY KWAK: I heard you’re from Jersey.

BRAVO: I am from Jersey.

KWAK: Do you identify as a Jersey girl?

BRAVO: Now I do, the longer I spend away from there. Because I’ve been in New York almost 10 years. It’s funnier to be from Jersey the longer you don’t have to be there.

KWAK: Truest thing I’ve heard. So you’re a mixed-media artist and your works actively engage with space in a way that’s reminiscent of Belkis Ayón Pa’que me quieras por siempre (To make you love me forever). How does this particular space lend itself to the viewing of your work?

BRAVO: I mean, when I think about Belkis Ayón, it was that intervention of the work coming off the wall and being something you had to move through. It becomes like a play set. I was always obsessed with that ideal, engaging in the space and bringing the viewer into it in a totally new way. In my MFA, I was making paintings and sculptures alongside each other, but I didn’t put them together so much. Ever since I saw [Ayón’s] work, I started to make Franken-paintings that were growing out of the wall. I wanted it to feel like the paintings were trying really hard to become real, but they couldn’t. When the painting and the sculpture feel related to the point where that line gets blurred, that’s where I’m most excited. I don’t like to just put a painting on a wall and call it a day.

KWAK: I want to ask about Silk Tosser. I don’t know if you have that one here.

BRAVO: Yeah, it’s right over here.

KWAK: I love the lil itty-bitty spider hanging from the armpit.

BRAVO: The fly? This is the first piece from the show and it sort of prompted the whole body of work. I made it almost a year ago now. I had been going through a very hard summer and thinking about how I was moving through the world, feeling really tiny and crushable. I wanted to feel super dangerous, I wanted to feel stronger, and I started to get really obsessed with spiders. This idea of a little thing that’s dangerous but also crushable. It sustains itself with its craft, and it makes its home wherever it is and it uses what’s around it to weave a world. I felt very much like that was what I was doing. I was using my resources to create something that allowed me to be much stronger than I physically was. It’s like the web of artwork, the storytelling of artwork, is a tool that allows me as the little spider walking around on it to be stronger, to take bigger strides, to collect things, to kill things that need to be killed, and to sustain myself.

KWAK: Is weaving a practice in your family?

BRAVO: I have a huge seamstress background in my family. My grandmothers on both sides worked in sweatshops for their whole lives basically. They were always working with textiles, and I brought that into my work when I started painting because I wanted to honor what they had done. Like, how ridiculous that they had to bust their asses all day for years of their lives so I could sit here and make a painting? But it does feel like I’m in conversation with them when I’m embroidering or using fabric. I always regret that they never taught me how to sew properly, so there’s an embarrassing sort of hand-sewn quality to everything.

KWAK: It feels like the set of a play, which makes so much sense because you’re piecing together family lore, material ephemera, and using nostalgia and imagination to materialize a speculative future. You’ve mentioned it’s a sort of imaginary afterlife utopia in the vague shape of Cuba, right?

BRAVO: Yeah. My interest in immersive shows began before I even started showing my artwork professionally. Coming out of an illustration background, everything was small, on a screen. Everybody was working on an iPad. I realized halfway through my undergraduate degree at Pratt that that was not the way I worked. I was lucky to have a couple professors who were really encouraging me to start painting. I knew that they had a drawing installation course at Pratt, and I wanted to finish my program doing that: transforming a space, doing sculpture, video, painting, full scale. My first painting was 70×100.

KWAK: Wow.

BRAVO: I wanted to shift the way I was working because I was so unhappy trying to illustrate. So from that point on, I had six months of access to a really disgusting basement in the bottom of Pratt, fighting bugs constantly. I transformed it into a sort of tribute to generational objects and home altar-making. From that point on, it was like, “Okay, these two things, painting and sculpture, have to live together.” Separating it always felt like I was trying to draw with my left hand. But there’s a lot of pressure in the market now to not do super immersive things.

KWAK: Yeah, the collectors are whores for paintings. I’m curious about the transmission of knowledge in regards to your family lore. Was it something that was important for your parents or grandparents to pass down to you, or was it something you had to inquire and probe for?

BRAVO: I have to search for it, for sure. I mean, my dad tells me stories. But he only has a limited knowledge. And both my grandparents died when I was in high school, so their stories kind of died with them. A lot of the history of their town and their lives, I’ve had to search for myself. And I’ve sort of taken responsibility for retelling it. But it’s not just a one-to-one retelling of my family history. It’s more a way of working out our differences by imagining a new familial mythology; maybe I will get to be the star this time.

KWAK: Tell me more about how the curio cabinet functions as a metaphor.

BRAVO: I grew up with a curio cabinet in my house. I would wake up early in the morning, go downstairs and play inside of it, and I would move all the little things around and make a little world. It was such an early introduction for me to my relation to objects and putting a lot of attachment onto them. It’s things you’ve decided need to be saved, but it’s not necessarily an archive because it’s not perfect. It’s like a collection of strange things that in some way can tell your story, what you care about, what’s important to you. I’ve always used curio cabinets in my sculptures, and this one in particular is a tribute to my dad, who was a boxer when he was in high school because he was the only Hispanic kid in town. He had to learn how to fight because people were going to beat him up if he didn’t do it first. But now my dad is much older, and he’s a little lazier, a little more complacent. He sits in his chair all day. He doesn’t have that temper that he used to have. It’s like he’s hung up the boxing gloves, so to speak. The figure inside is more representative of me, and she’s kind of tapping into that temper. The rage of the bull is coming through her, I guess, as I sort of mature into that age when he was that kind of guy. So much of this show is about the idea that it’s inevitable that you turn into your family members. But you don’t have to be horrified by it.

KWAK: In the past, you’ve had more of an adversarial relationship to the figures in your works, but now you’ve come to embrace them. What changed?

BRAVO: There’s generational conflict that’s really specific to Cuban-Americans. My grandparents left Cuba before the revolution. They were poor. They lived in the countryside. They had no money. They just needed to get to America, where everybody was going. They didn’t know all the Cubans were going to go to Miami, so they went to New York. Over time, their family started coming over during the revolution, and then other wealthy Cubans came over during the revolution. The rhetoric around the Cuban Revolution became very pointed in America. I think that gave them ideas about what was going on in their home. And now, it’s challenging to reckon with their beliefs as someone with a much more revolutionary mindset than them. In the old work, I felt frustrated because I was like, “You guys were the people that the Revolution was trying to help.” But I understand it now. You can’t blame them, they were a product of their environment and where they ended up. Instead of trying to fight against who they were or what they may have thought, you just have to accept it and move on because they’re gone.

KWAK: Who are these powerful figures that recur in your work? They remind me of the Amazons.

BRAVO: When I tried to start painting, I wanted to make people that felt like imaginary family members, but maybe imaginary family members that I would get along with better. And then over time, they just started getting closer and closer to looking like weird avatars of me. It’s like the video game version of yourself that’s cooler and has more powers. It’s sort of how I would want to move through the world. She’s feminine, but masculine at the same time. She’s strong, she can turn into anything she wants to, and she’s in cahoots with her little tribe of other girlies. They’re projections. They’re something that I want to be. They have this blank stare. None of them have eyes because I want it to be very clear that they’ve never actually been alive or they couldn’t live in any real way.

KWAK: Beyond your family, are there any writers or poets or musicians who’ve served as role models to you?

BRAVO: I was such an indie music kid in high school. I was a Tumblrina. I was obsessed with Sufjan Stevens. He wasn’t afraid to try anything. And it meant a lot to me that he was able to use something so personal to communicate something so universal. Everybody’s always like, “He’s so sad. His life is so sad.” But I think he’s figuring it out. If you make something from it, you can heal it. And then I got really inspired after I read Reinaldo Arenas’ memoir Before Night Falls. He was a Cuban writer who left during the revolution and he had this really interesting perspective on the feeling that being queer in Cuba was in itself a secret society, but everybody was doing it. He lived out in the farmland when he was younger, which is where my family’s from, and he was like, “There was not a man in that area that did not have sex with another man, but none of them would say they were gay.” There were definitely members of my family that were involved, but there’s no trace of it. It gets erased by what we’re supposed to keep as the family history, the “good” parts. I’m more interested in pulling the cracks of the family history open and creating something new inside of it. What don’t we know? What could grow from that?

KWAK: I heard you watch reality TV sometimes when you work.

BRAVO: I do. I watch it exclusively. I’ve watched all of Survivor twice, which is psychotic behavior. There’s like, 45 seasons. And then I grew up watching Real Housewives, so pretty much all of that is fair game.

KWAK: Are you keeping up with Love Island?

BRAVO: Oh, yeah. I just finished Love Island.

KWAK: Do you have a favorite couple from the show?

BRAVO: Bruh. Well, my favorite couple just broke up: Molly Mae and Tommy. From Love Island US, JaNa and Kenny.

KWAK: Obsessed. Is your family coming to the opening?

BRAVO: Yeah, they’re coming. My mom, she crocheted these spider webs.

KWAK: Oh, wow.

BRAVO: I asked her if she could make me a spiderweb for the show. She made me four. She became obsessed. She wanted to be an artist, so she gets really excited by everything I do. It’s a weird line for me to walk where I’m making work that’s very personal about the family, but I’m also trying to be protective of people’s personal information. There’s conflict, but I don’t want to be so explicit about what it is all the time. But more than anything, it’s still a way of honoring our family as a unit. And that comes with conflict, that comes with a great deal of love, and I wouldn’t have half these generational objects if people didn’t love me and save them for me. So I think they’re proud of it.

KWAK: I hope you’re proud of your show. This is so awesome.

BRAVO: I feel proud of this one. Yeah, I do.