Ari Marcopoulos

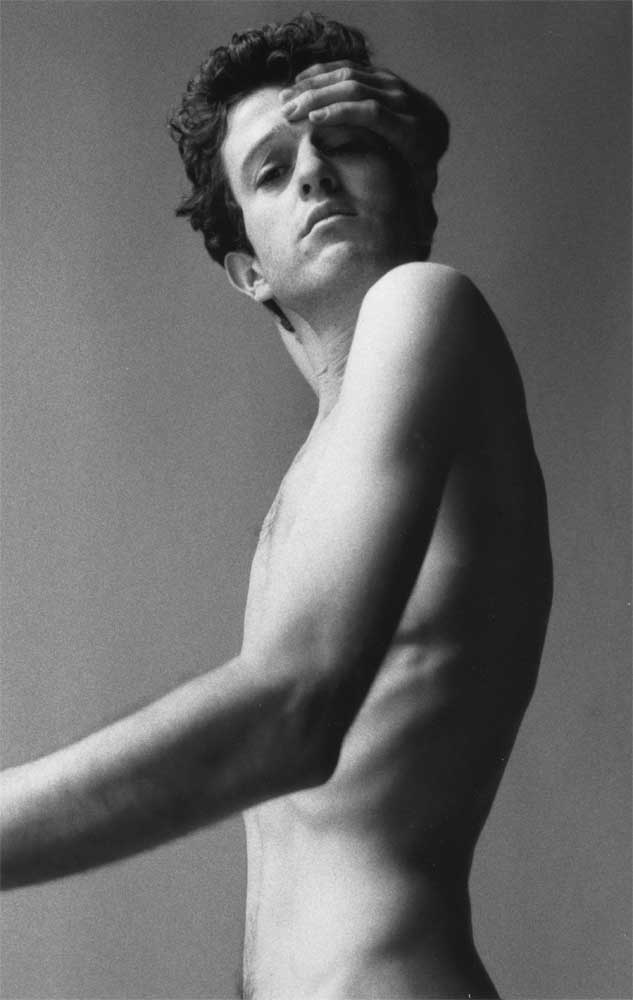

Dutch photographer Ari Marcopoulos moved to New York in 1980 in his early twenties and wasted no time in becoming one of the key artistic documentarians of American culture for the next three decades. His work doesn’t follow mainstream enthusiasms. Rather, Marcopoulos’s photographs have routinely—and sometimes at great risk to the man—slipped into the subversive, hardtoreach pockets of American life, from the burgeoning hiphop and downtown art scenes of New York in the 1980s to the nomadic snowboard circuit of the 1990s and even the closertohand studies that Marcopoulos has made of his own family in Northern California throughout the ’00s. The 52yearold Marcopoulos is an inimitable artist who has as much charm and personality as he does the rare ability to see a jarring photograph in places the rest of us might overlook. This fall, he is the subject of a midcareer survey—“Within Arm’s Reach,” at the University of California, Berkeley Art Museum—which will include everything from early blackandwhite street shots to his latest videos, such as one filmed earlier this year in Detroit of two young kids making beats. Here, Marcopoulos talks to his friend the Los Angeles–based painter Dave Muller about how he got into photography and how he almost got himself killed pretending to know how to snowboard.

DAVE MULLER: You’re in New York right now. How’s the weather?

ARI MARCOPOULOS: It’s gray, which for me is ideal. I love flat light. It’s a good day for taking pictures.

MULLER: Do you remember the weather when you first moved to New York?

MARCOPOULOS: No, because something way more traumatic happened right after I arrived.

MULLER: What?

MARCOPOULOS: When I woke up the next morning, there was the headline that John Lennon had been shot and killed.

MULLER: It was December 1980. I remember being in junior high school and they told us at lunchtime.

MARCOPOULOS: In New York, unlike Holland, there are newspaper stands on every corner. That was a big headline all over the city. So the weather those days sort of escapes me . . .

MULLER: Why did you move to New York in the first place?

MARCOPOULOS: Because, in Holland, things were pretty stale for me. Even though there were a lot of good influences and a certain openness to music and art and literature, I just wanted to go somewhere less familiar—somewhere bigger. Holland is a fairly small country, and in a weird way, somewhat conservative. That might surprise people because it is a very tolerant place, but it’s also a somewhat Calvinist country. There isn’t much flexibility in changing people’s perspectives. I was living in a suburb of Amsterdam, so I could have moved to Amsterdam, or Paris, or London . . . I ended up in New York because it was far more attractive to me. Weirdly enough, one reason was because I was interested in sports like basketball and baseball. I had visited New York before, at age 12, and I loved the big buildings and the swarms of people. At 23, I decided to try it. I was going to go for six months, and I ended up living there for 18 years before I moved to California, so I am living the American Dream.

MULLER: Your work seems like a process of thinking quickly on your feet. Like it involves having to figure out something and take advantage fast. If you sat there and ruminated, you’d miss it.

MARCOPOULOS: Often, that is true. A lot of my work comes through accidents or circumstances that just happen to present themselves. I have to realize that something is presenting itself. Otherwise it slips right by. But sometimes there is more involvement with setup—maybe more in my video work than in my photo work. In any case, I use my personality. I’m a very curious person. And most people are charmed by curiosity—especially if you are curious about them or what they are doing . . . unless they are breaking into a car or something.

MULLER: Then you have to act quickly and run like hell.

MARCOPOULOS: [laughs] I think I’m predominantly known for my portraits. Obviously in my work there are landscape or stilllife elements, but mainly my work is people . . . be it my children or friends or whomever. And I don’t try to impose myself on them. I don’t really get too much into asking people to put on different clothes or force them into a different space. For about the last 10 years, I’ve really been working with my kids and making them the subject of my photographs, which has become more of a collaboration, like shooting my sons when they’re kicking it around the house or going for hikes in the woods. But, you know, my photography has really always been about what I feel I’m getting out of it. What people on the outside get doesn’t concern me.

MULLER: Yeah, the old Ian Curtis thing. We do it for ourselves. If other people like it, that’s okay.

MARCOPOULOS: Exactly. And we do it because we don’t know what else to do.

MULLER: That’s true. My wife was saying just today, “I don’t know what else Dave would be doing if he weren’t painting. This is the only thing he knows how to do.”

MARCOPOULOS: I know. I always thought that I was lazy because I could never tell if I was working or not. I was making things, which doesn’t seem like work. But whenever I told people that, they’d say, “Are you crazy? You have a huge output. So many books, zines, videos. So many things . . . ”

MULLER: In the ’90s, you concentrated on a group of snowboarders, following them around and taking some intimate images. How did you fall into the snowboarding circuit?

MARCOPOULOS: Around 1995, Burton Snowboards contacted me to see if I wanted to do their campaign for them. I lied and said that I knew how to get around in the snow. I had no idea how to ski or snowboard. I ended up on a glacier in the Alps. The first day I went out with this crew of snowboarders, I had a big backpack on with my cameras in it. The second we stepped on the snow, I fell down and couldn’t get up because my backpack was so heavy. The guys were all in shock, but in the end I earned a lot of respect from them because they were amazed I said yes. Terje Haakonsen, who was the best snowboarder at that time, was particularly welcoming. He really let me into the club. Within a year, I was getting out of helicopters in Alaska, snowboarding right along with these guys. I spent six years following them, making it into my project.

MULLER: Have you ever considered what you do as being more of an ethnographer than an artist? You know, going around and bringing back documents from different places.

MARCOPOULOS: I do feel a kinship with anthropology or ethnography, although when you hear those terms you think of something exotic. Generally, photographic anthropology has that taste of the faraway or undiscovered place. But my anthropology has more to do with what’s in my reach.

MULLER: So instead of the final frontier, it’s more like the inner frontier?

MARCOPOULOS: Yes. That’s a good way to put it. Sometimes when people look at the work I’ve done with my family, they think it’s autobiographical. But it really isn’t. It’s more about the idea of family.

MULLER: More archetypes of family.

MARCOPOULOS: When you say you remember falling off your bike and getting stitches in your head, I think, I have photographs that tap into that collective memory. I also think that another interesting element is that as my sons went into teenagehood, they started to look like some of the groups of people that I had photographed previously. They started to become like my old subjects. As if, as a photographer, you come around to the same visual points. I’m pretty solitary when I take pictures, you know. Even when I take pictures of people, I just go about my own way of doing it. When you’re with people that are aware of the fact that you’re a photographer, they’ll say, “Oh, look at that! That’s something to take a picture of!” That’s almost a sure sign that you shouldn’t do it.

MULLER: What’s the oldest piece you’re going to have in the show at Berkeley?

MARCOPOULOS: That might be the portrait of Alan Vega. It stems from around 1981, I think. I purposely chose not to show earlier pictures, say, from the Netherlands. Coming to New York and being in New York is when I really started to develop where I was going with my work. But you know, even then I never went out saying, I’m going to photograph all the hiphop people in New York. It wasn’t like that. It’s just that I noticed one thing going on—the hiphop style translated into sneakers with fat laces and Lee jeans. I was fascinated by it, so I photographed some of that on the streets, most of the time being intimidated by what was around me. But I would run into the Fat Boys by accident and photograph them. And then somebody asked me to shoot Public Enemy, and I got picked up in a Jeep by Hank Shocklee, their producer, and he drove me to Roosevelt, Long Island, where they’re from. They were all waiting for me in a parking lot. But I didn’t cross Public Enemy off my hiphop list afterward and go to the next one. It wasn’t like that. Whenever I lecture at a school about my work, I say, “I liken myself to lying in a stream and just sort of going with that flow, you know, letting the current take you where it takes you.” That’s not to say I don’t let things influence me.

MULLER: You shot portraits of a lot of heroes in the ’80s—Warhol, Mapplethorpe, Basquiat. How did that iconic photograph of Basquiat in his bathtub happen?

MARCOPOULOS: That one was taken at his place on Crosby Street in 1983. We were hanging out all night, and he had to split the next morning to Tokyo for a show. He just stuffed all his clothes, sketchbooks, and oilsticks into a duffel bag, and before he left, he took a bath. I just stayed with the program and took some photos. I was excited when he was washing his hair. It reminded me of the Man Ray portrait of Duchamp.

MULLER: Was it tricky to put together a survey of all your work?

MARCOPOULOS: Yeah. I’m also learning now what a survey is. You can’t just go and do your own installation. A survey is how a museum looks at your work. It’s like an archaeological dig by a curator. At first I treated it like an installation, and then, of course, lately I’ve been quite minimal. But it is a collaboration, and I’m excited about it. It’s going in the right direction, and I want to leave some room for unexpected possibilities. I mean, lately I keep working because I read that when Bruce Nauman had his midcareer survey, he did nothing for the next four years!

MULLER: [laughs] Don’t let that happen to you, Ari! What would four years of nothing be like?

MARCOPOULOS: I’m getting scared!

Click here to see more work by Ari Marcopoulos.

Dave Muller is a Los Angeles–based artist and musician