Adrian Tomine and Tavi Gevinson on Turning Anguish Into Art: “Someday, This Will Be Good Material”

Adrian Tomine’s new book opens with a quote from Daniel Clowes about being one of the world’s most famous cartoonists: “That’s like being the most famous badminton player.” Such is the tone set by Tomine before we’re even introduced to him in The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist, a graphic memoir that begins in Fresno in 1982, when a young Tomine, on his first day at a new school, tells the class about his career aspirations. “Oh, a famous cartoonist!” his teacher says. “Like Walt Disney?” “No,” Tomine replies while the other students snicker at his response. “Like John Romita.”

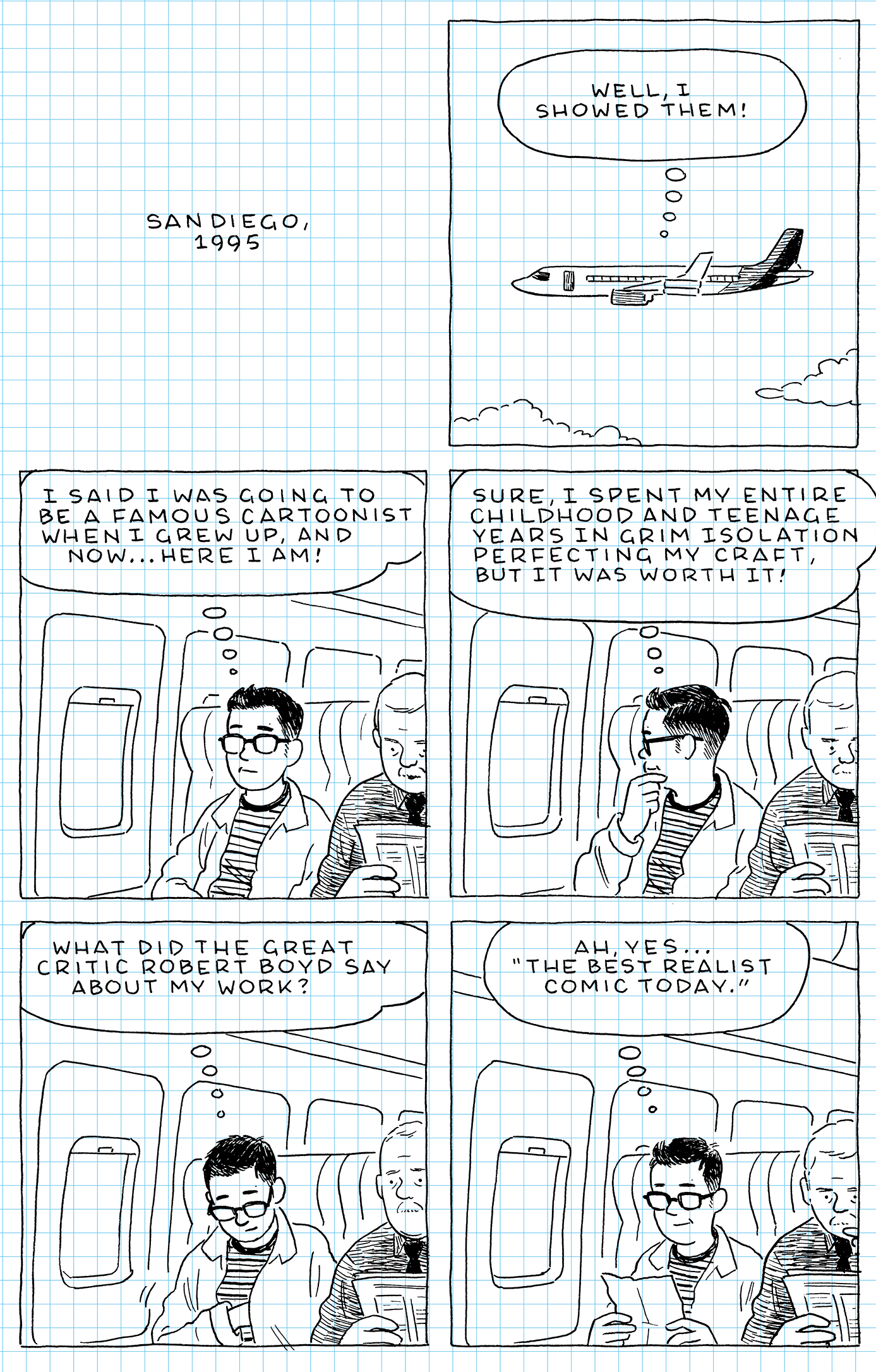

Fast-forward to 1995. Tomine, now an exciting new voice in comics, is on a plane to San Diego. To kickstart his confidence for Comic-Con, he takes from his jacket pocket some of his more favorable press clippings, including one by Clowes himself, who said, “Drawn and Quarterly [the Canadian imprint that publishes Tomine’s work] keep their perfect record intact by signing up the boy wonder of mini-comics.” But where there’s a balloon, there is a needle to pop it. Later that night, back at his hotel room, we find Tomine curled into a fetal position obsessing over a more recent review: “Haven’t we seen a little too much of the hip, muted, fragmented, overly-short short stories that this moron is trying to pass off as fresh and original?”

The rest of these vignettes, sort of spiritual cousins to the HBO series The Comeback, careen between triumph and gut-plunging embarrassment, sometimes all within the same little square box. But the culmination of these cross-stitched memories offers the reader so much more than the sum of its parts. Near the end of the book, when a medical issue forces Tomine to consider his own mortality, he writes a goodbye letter to his daughters, Nora and May. The act of writing it is hilarious (Tomine’s condition turns out to be a combination of anxiety and acid reflux), and yet, what he has written, as with much of The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist, is heartbreaking.

On an afternoon in late June from her home in New York, the writer and actor Tavi Gevinson called Tomine to talk about survival, success, and finding the funny in life’s little pains. —NICK HARAMIS

———

TAVI GEVINSON: There’s so much that I want to talk to you about.

ADRIAN TOMINE: Oh, thank you.

GEVINSON: I want to know if since social distancing started you thought a memoir called The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist would resonate differently.

TOMINE: It does feel weird to promote a book that was conceived before the whole world and my life changed completely. It’s almost nostalgic looking at this book now, even though it hasn’t even come out yet. Looking back at an easier time or something. Since I was a kid, I’ve spent a big chunk of almost every day of my life sitting alone in a room writing or drawing. And so, for the last four months I’ve had very little of that and it’s been such a weird adjustment. And I think the book is a bit dismissive or critical of my career and the weird life that I’ve built for myself, and now I’m sort of thinking, “Gosh, I really miss that. That was an awesome life that I had.”

GEVINSON: That’s natural. Everything looks different now. I miss things I didn’t expect to miss. Why do your first full-length memoir now?

TOMINE: It’s partially because I have this ongoing voice in the back of my head that’s telling me that there’s always a clock ticking, that whatever readership I might have built, it’s just a matter of time before they get sick of me and my work. I’ve wanted to forestall that as much as possible, to try and make each new book at least somewhat different from the previous one. Every book is a reaction to the one that came before it, and since the book before this one was fiction—short stories and mostly full color—I wanted to try not to repeat that. I will admit that there some part of my brain was probably thinking, “I bet people are interested in looking behind the curtain.”

GEVINSON: We’ve talked before about readers thinking your stories were autobiographical anyways. Was it freeing in any way to be like, “It’s just going to be about me”?

TOMINE: This was the easiest book I’ve ever written. I didn’t have to invent plot elements or anything like that. I didn’t have to think about what comes next. In the past, I would go through this arduous process of handwriting things and typing things up on the computer so I could edit it and then sketch it out. For this, I was able to just basically write each story in my head and then put it down onto paper pretty quickly. But emotionally or psychologically, I feel a lot freer writing fiction than when I’m drawing myself and having to think about how this is going to resonate with real people in my life, and being worried about my daughters growing up and reading it when they’re older.

GEVINSON: In our last interview, you talked about developing a connection with the characters you draw, and I thought about that reading this book, because you draw yourself, but also your family. What was that experience like?

TOMINE: Developing the intimacy with myself of drawing myself? [Laughs.] Drawing myself has been second nature for so long that I didn’t really think about it. For the most part, I didn’t worry about the depiction of myself, but it was more about other people from real life that I depicted in the book. I was surprised to find that my older daughter ended up being the first reader of any of this material because she would come into my room and read the pages as they were in progress. I thought that at a certain point she would just get bored with it, but of course as the book progresses, it comes closer to her appearance in the narrative. So she got more interested, and at a certain point, I walked into my room and she was sitting there and had actually found the notebook where I had the rough draft of the book, and was reading ahead into the rough draft to see where it went before I’d even finished drawing the real pages.

GEVINSON: What were her reactions like?

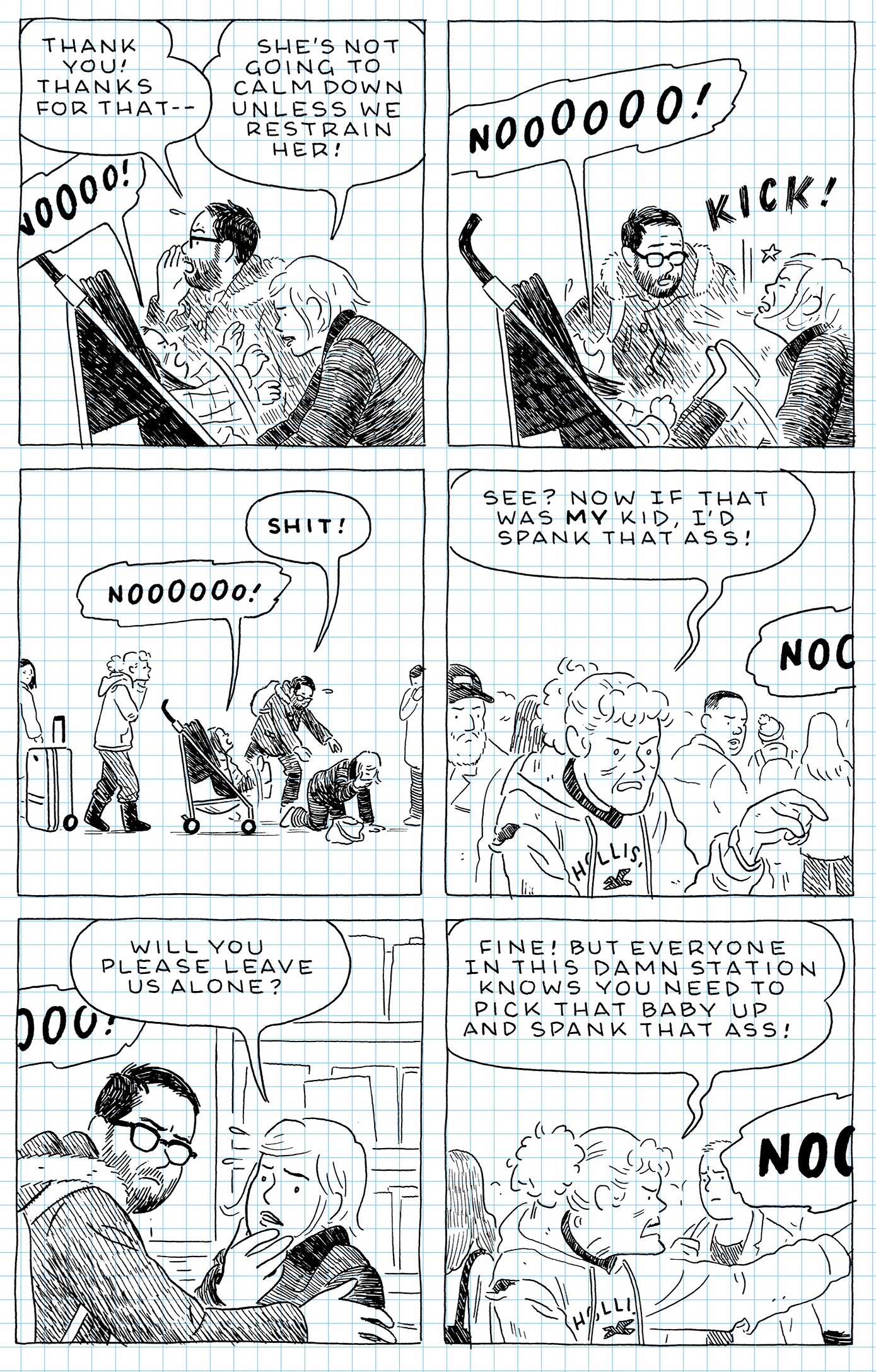

TOMINE: She would get a little technical about the chronology. Talk about a lie detector, she’d absolutely point out any distortion or slight fictionalization I did to material that she had been privy to, even things I know she’s too young to actually remember, but she’s heard us recount enough times that she could fact-check my comic version of it. The one where she has a tantrum in Penn Station, there are a few elements that are a bit changed from real life, and she instantly caught them, and was put off by the fact that her dad was lying, basically.

GEVINSON: I know of an actress who, when she works on her lines at home, her son will yell out, “Real, fake, real.”

TOMINE: Amazing, amazing, amazing. Yeah, like right now I’m working on a cover for The New Yorker, and I get plenty of feedback from the people at the magazine, but I’m living in terror of Nora coming into the room, because she won’t actually criticize anything, but she does have a way of asking a question innocently that completely fucks up my progress, because it’s like, “Oh, you’re right, that is really confusing,” or, “That’s true, that doesn’t make sense.” And for a minute, I get mad at her, and I think that she’s not getting it, but then I realize she is getting it and that I need to think about it. It’s just good to have sort of that unfiltered gut response from someone.

GEVINSON: And May is too young to read it?

TOMINE: She’s too young, but I’ve been working on this book as long as her memory is active. One time she said kids at school were talking about what their parents do. And just out of curiosity, I asked her what my job was, and she said, “You draw pictures of yourself.”

GEVINSON: A lot of the stories feel like the kind that you might retell a lot, socially, that change as you learn to make them more entertaining. I wonder if you discovered anything new about them once you wrote them down.

TOMINE: I did. The versions of the stories that are in the book have completely overwritten actual history in my mind, and at this point, I honestly believe that some of the slight distortion is reality. It’s probably a good thing that this is coming out at a time of no socializing, because I could totally imagine being at a party with Sarah, and me telling one of these stories, and her being able to tell that I’m telling the fake version of it. And I could just imagine her thinking what a self-involved phony she’s married to now: “He’s not only retelling these same anecdotes, but now they’re revised in a way that he thought would make them funnier.”

GEVINSON: Well, to be fair, what reason is there to tell a story at a party if not to entertain?

TOMINE: Fortunately she’s from an Irish family from Brooklyn, so she’s very understanding of distorting facts to arrive at a better story, especially in service of humor.

GEVINSON: One thing I love about the book, or that’s surprising and different about it, is that a lot of stories about young artists, especially memoirs, are about how they found their voice. When it starts, it feels like the you who’s on the page is already a cartoonist. It’s about you finding new ways for non-work life to inform your work and also be meaningful on its own.

TOMINE: I think that’s right. I wasn’t consciously rebelling against that tradition, but I think I was sort of doing a bit of a bait-and-switch with the title and what it looks like. I think people will come to it thinking, “I’m going to learn how he became a cartoonist,” and it really, to me, ended up reflecting this weird aspect of my life, which is that I didn’t have to struggle to become an artist at all. That was the part that came very naturally to me. The long struggle for me was about things that come more naturally to other people—how to be an adult, how to be a parent, and how to be generous with people—things that are more second nature to some people, in the way that making comics was second nature to me. When you were asking the question, I was wondering what your arc was like.

GEVINSON: I feel like that’s sort of what I’m talking around, is that it’s about how, when you devote a lot of your time to developing in certain ways, you don’t develop in other ways. And also, the ability to communicate to an audience is not the same as being socialized.

TOMINE: Yeah. I feel like I could not have arrived at this point that I’m at, in my career, if I hadn’t started when I was so young and devoted so much time to it and everything. But at the same time, I have this vision of what an alternate path might’ve looked like if I had been more engaged with the world, and spent less time sitting in a room by myself, at a drawing table, throughout my whole life. And I was hoping that I would finish the book and I would arrive at a strong stance on that, but I kind of have equally balanced, mixed feelings about it. And like I say in the book, at this point, as a parent, I definitely would not recommend the life that I had to my children.

GEVINSON: Right. But I also think you can’t really entertain an alternate universe, where like…

TOMINE: Oh, I always do. I’m constantly entertaining an alternate universe.

GEVINSON: [Laughs] You can, you literally can. But I think maybe you would have just been wishing you were inside all the time.

TOMINE: Yeah. And of course, the truth is it wasn’t like there was ever a point in my life where I had two equivalent paths available to me.

GEVINSON: The book reminded me again of our last interview where I asked you some question that a reader had sent in about sticking with something like cartooning if they’re afraid of rejection, and you were kind of like, “Oh, you just have to have low expectations and know that all of that is part of it.” The book helps make all of those little pains funny.

TOMINE: Well, I love that we’re getting to sort of revisit that old interview and update it. I think maybe what I said was the responsible, parental thing to say, which is to keep your expectations modest and just do it for the love of the work. I still stand by it, but I think if I’m honest with myself, I’ve sort of promoted this narrative of being this humble nebbish guy who’s just doing the work cause he loved it, but I also think maybe it’s useful to be transparent and say that when I was a kid, I would spend more time designing back covers of hypothetical books of mine, and writing blurbs by actual famous people praising my work. And I would create these things without ever actually having created the book that it was supposedly attached to, so there was definitely some disgusting part of my brain, even as a child, that was like, I want to be published and I want to get praise from people who are more well known than me, and I think that might have been part of what propelled that artistic motivation. And you would hate to go to an art school right now and say to a bunch of freshmen, “You know what you can do? You design the back cover of your book and you write quotes from all your heroes.” But I feel like this whole book is me trying to be kind of honest about how I evolved as an artist, and as a person, and that’s one of those kind of cringe-y memories that’s been popping up in my head lately.

GEVINSON: I think to be making art with the intention of sharing it, you need some sort of ego. Was it a conscious decision for the book to not be about craft? Or do you see it as being about craft?

TOMINE: No, it’s not, and I feel bad that some people might be going to it looking for that. There are certain things that I’ve even mentioned in interviews that I skipped over completely in the book. One of the big things is that there’s no doubt in my mind that I had some incredible mentorship experiences from other artists who probably would never want to take credit for that, or would never think that they had done that for me, but they definitely did. And that gets kind of glossed over in the book because I was trying not to expose much about anyone else besides myself. I honestly think that all the stuff about being a cartoonist is just kind of the enticement to get people to read it and see these funny gags, but to me, it’s the last part of the book that is really the heart of it for me.

GEVINSON: And even though it’s not about craft, exactly, I think that part is where the work gets a new meaning, after seeming meaningless for a bit. I wanted to ask—there are the stories about your stalker or you quoting a bad review. I would be too proud to include stuff like that, or I would develop some other game in my head where I win by not including those things.

TOMINE: Well, this is a game, and it’s a very long game, too, because when those things happened to me, the only consolation I had in the pits of my despair was the totally corny thought that, “Well, maybe someday this will all be good material.” It’s almost like I told myself that so many times that I actually had to create this book so that, in hindsight, I wouldn’t have this litany of horrible memories.

GEVINSON: Right.

TOMINE: To be honest, it’s much easier for me to quote an over-the-top negative review, because it’s almost like I’m pointing out how absurd it was. What was harder for me to write was the story where Sarah and I go to a Japanese restaurant in Brooklyn, and at the table next to us was a young couple, and the minute we sat down they began discussing one of my old books. The guy in the couple was such an eloquent and insightful critic of my work, and he just eviscerated it in a way that every single thing he said was like a dagger in my heart. It seemed to be speaking for what the general public was thinking, but was too afraid to say, and maybe even what Sarah had thought when she first read my book, but was too polite to say. To recreate that dialogue was actually a lot more painful for me.

GEVINSON: I’m writing a book, and I reread some stuff I’ve written over the past year, my fear is that I’m not creating anything of substance and I’m just airing my grievances. Reading your book, I was like, “How do I make these stories of being embarrassed or ashamed or burned have meaning beyond my venting?”

TOMINE: I don’t know that they’re mutually exclusive, the idea of you venting or settling a score, or something like that, and creating something of substance. I’ve read this book of interviews that Orson Welles did with Peter Bogdanovich right before he died [This Is Orson Welles] that, to me, is the best book about Orson Welles. There are more artful biographies of him, and there’s critical analysis of his work, but that book of interviews is the one that most brought him to life and gave me the most insight into his creative process and how he felt about the business and his peers.

GEVINSON: It reminds me of when we were talking a couple months ago about the new Fiona Apple album and you said it reminded you of underground cartoonists in the way that minor events take on big meanings.

TOMINE: Yeah, I have been listening to that album since it came out. I’ve always been attracted to art, whether it’s music or literature or film or comics, that has that feeling of putting the reader inside the artist’s brain for a little while, warts and all. The more unvarnished, the better. I think that this new book was my very polite attempt at trying to do something in that realm.

GEVINSON: Are there other artists who you think do that really well?

TOMINE: In underground or alternative comics, there’s been a long history of that, especially before there was any money to be made and it was just like the only people who were putting out these comics were not anyone who had any thoughts of a career or anything like that, but had like this absolute compulsion to put these things down on paper.

One of the first cartoonists I ever met as a kid, named Justin Green, did some of the earliest confessional autobiographical comics. He’s a great example of that. Outside of comics, I think of someone like Daniel Johnston. Listening to one of his albums is like seeing the world through his eyes.

GEVINSON: What do you feel like you’re able to do in cartooning that you can’t in anything else?

TOMINE: That’s been on my mind a lot lately because I’ve been trying to do screenwriting, and there’s a lot about it that’s exciting and appealing, but at the end of the day, I have this relief when I see my drawing board and feel like, “If I really wanted to, I could tell this story that I’m trying to get out into the world with great difficulty, as a comic.” I wouldn’t have to wait for anybody’s permission. I wouldn’t have to get any funding, and I could start immediately. There’s something to be said about doing art that doesn’t have a huge expense in terms of creating it. It engenders a lot more freedom and takes some scrutiny off you.

GEVINSON: What are the limits of your medium?

TOMINE: That’s really the focus of this book. Different cartoonists I know have different opinions on this. Some will totally agree, and some will vehemently disagree, and think I’m being intentionally cynical or something, but there’s a part of me that does think there’s something about the art of making comics and the process of it that is mentally damaging. It’s the idea of having no coworkers and being alone for that long, all the things that I love about it, and going through this very slow, methodical process of funneling the grandeur and the spontaneity and the liveliness of real life into these square boxes. There’s just such a long history of cartoonists at the end of their life or at the end of their career who are not in a good place.

GEVINSON: Well, on that note, who, in your opinion, is the most cartoonist-y non-cartoonist artist?

TOMINE: I remember when I saw Welcome to the Dollhouse years ago, having the feeling that in another world, Todd Solondz would be an underground cartoonist. I had that feeling a bit when I saw Uncut Gems. I remember thinking it when I watched Fleabag, too. I feel like maybe I’m trying to get at some quality of an artist putting stuff into their work that maybe they think is only going to resonate with them or their friends or something. Then, magically, it works for a wider audience.

GEVINSON: It’s like the amount of control that you get as a cartoonist necessitates a kind of self-indulgence that maybe in other mediums—at least in my work as a writer—I feel so self-conscious about.

TOMINE: I feel like you’re in a far tougher bind than I would be in that regard, because you’ve made such a generous, personal connection to your audience in a way that’s much deeper than I ever have. You must feel a lot of eyes upon you as you’re working.

GEVINSON: I think you write toward the reader that you want. Most Rookie readers wouldn’t want to read something by someone who has censored or edited themselves to be more helpful or likable, so that helps me.

TOMINE: Do you feel the obligation of being a role model, though? Because that’s nothing that has ever occurred to me.

GEVINSON: I felt that way doing Rookie, and I think I was mostly imagining it. I’m not an elected official. I don’t think people actually care that much about what I do. I think that expectation is the enemy of good art for all the reasons we’re saying, because it makes me think more about how I’m coming off than what I’m actually expressing.

TOMINE: I think you’re definitely selling yourself short in terms of how much you meant to a lot of people. But I don’t get the sense that you are actually this evil person who’s stifling all your impulses.

GEVINSON: Yeah, I’m waiting to come out as Q-Anon.

TOMINE: I think that you can find some easy harmony between art that is authentic to you and work that will be satisfying and helpful to readers.

GEVINSON: In our last interview, you said, “That became a conscious goal for me when I closed that door to my studio, to just shut that all out and try in some way to reconnect with the teenage version of me that was doing this stuff because he enjoyed it.” I want to know if that still feels like a goal for you when you work?

TOMINE: I think that’s still my goal whenever I’m working on comics, but it’s an inherently unattainable goal. I don’t think I could ever fully block out all the concerns and the realities of what it means to work on a book now. I guess it’s just that feeling of aiming for something unattainable, and arriving at something that’s halfway there, and that’s still better than nothing. But I think there’s also a history of cartoonists who don’t need any encouragement and can do that by default, and they build a career of just doing stuff that appeals to their childhood version of themselves.

GEVINSON: Obviously, you’ve been doing this professionally from a young age, but when your responsibilities extended to your family, did that explicitly change your relationship to the actual work of writing and drawing?

TOMINE: I think I’ve been lucky in that my work has never been in danger of being massively commercial. It’s not like I’m really close to writing a superhero movie screenplay, but I’m holding out for reasons of integrity. There aren’t a lot of instances in my life where I’ve felt like I had that classic artist’s choice between the work I love and the work that will make me rich, because obviously I’d have chosen the work that would have made me rich at this point. But I haven’t had to make that call. You kind of did what I fantasize about. You totally stopped the train that you were stuck on since you were a kid, got off, and you’re doing other things that you’re excited about.

GEVINSON: I will say my life is 100 to 1000 percent less stressful and more pleasurable solely from a time perspective. I can just engage with the stuff that I’m interested in more deeply in a way that I just couldn’t when I was trying to make a business survive and produce daily content. But now I’m learning how it could actually help me to think of writing as more of a job and not like, “The book is my soul.”

TOMINE: Are you worried about reactions from people who you might be referencing?

GEVINSON: No. I was, but I don’t really feel that now.

TOMINE: What changed for you?

GEVINSON: I think I had to unlearn a lot of conditioning around what kinds of stories people, specifically women, are allowed to tell. I think there was a time when I was so obsessed with, “What’s okay to say? What isn’t?” Every writer I interviewed, I wanted to know where they stood on writing about people. The people who I think wouldn’t want to be written about and who I’m very close to and who I love, but about whom I have a story that’s not really flattering—including it in the writing is not important enough to me. It’s easier to let those things go. I’m actually like, “Oh, it’s better to be challenged to have to think of another way of conveying that emotional information rather than this anecdote.”

TOMINE: What do you mean by certain types of stories that you think women are conditioned to tell?

GEVINSON: First, there’s the problem of the triumphalism of memoir. Rookie was for teenagers. While we tried to make space for stories where writers could reflect on being in situations that were complex, I think there was an expectation that personal stories would end with some kind of like, “And then I learned about internalized misogyny and here’s what fixed me.” So there’s unlearning that narrative, which is probably also connected to the role model thing. Then, I think women and men are taught to center men in stories, and center their moral character, center their reputations. Down to even the way I have processed my own experiences privately, as though to even acknowledge that another person’s actions were wrong meant already taking him to court or something. It’s taken a few years to understand how much guilt was standing between me and what I was trying to write, if the stuff I’m trying to write is unflattering for other people—for men.

TOMINE: Wow. I don’t know if you’ve had this experience yet, but I’ve found that if there was maybe a score I wanted to settle or something like that, when the time came, I’d look up the person in question and find out more about them and there would be an instant shift. Suddenly I’d feel like I didn’t need to publicly settle that score anymore.

GEVINSON: No, it’s more that I feel a responsibility toward some people and not others. Do you have time for one more question?

TOMINE: Yes.

GEVINSON: Were there any specific influences on this one?

TOMINE: I think really this book is, by design, the closest I’ve come to doing cartooning that’s like handwriting, where it kind of just flows naturally. In past books, I would literally waste a whole day thinking, “How should I draw clouds? I don’t want them to look exactly like the way Dan Clowes draws clouds.” Or sometimes it’s the reverse of that. It’s like, “How have artistic heroes of mine done it?” In this book, I tried to really free myself of those neuroses. I feel like my whole career has been this quest to find my authentic style. I really learned everything through imitation and lifting elements of other people’s styles and incorporating them into my own, so it’s kind of haunted me for a long time. Is there anything that I do that is just mine, or is everything an amalgamation of all my influences?

GEVINSON: That’s sort of a running joke in it, people telling you you’re copying other people.

TOMINE: It’s been a running joke all my life, really. Again, some of those things in the book that are funny anecdotes now really, at the time, made me want to go back to my hotel room and jump out the window.