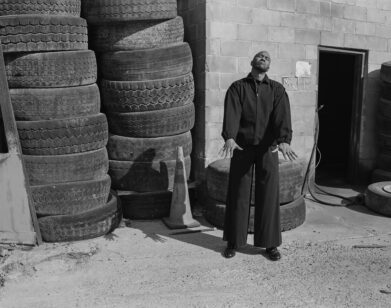

Tavi Gevinson

ABOVE: TAVI GEVINSON IN NEW YORK, JULY 2014. DRESS: MAISON MARTIN MARGIELA. RINGS (FROM LEFT): RUIFIER, CATBIRD, AND SASKIA DIEZ. STYLING: JESSICA DOS REMEDIOS. COSMETICS: NARS, INCLUDING DUAL-INTENSITY EYESHADOW IN HIMALIA AND LARGER THAN LIFE LONG-WEAR EYELINER IN VIA VENETO. HAIR PRODUCTS: R + CO, INCLUDING MANNEQUIN STYLING PASTE AND ONE PREP SPRAY. HAIR: JOEY GEORGE/ARTLIST. MAKEUP: MARLA BELT FOR NARS/STREETERS. MANICURE: ERI HANDA FOR DIOR VERNIS/MELBOURNE ARTISTS MANAGEMENT.

You know her story: Tavi Gevinson was born in Chicago in 1996, the youngest of three girls. Her father was a high school English teacher (he is now retired) and her mother, a weaver. At 11, Gevinson started blogging about fashion under the moniker Style Rookie, and even before she had begun high school, was invited to sit front row at the couture shows in Paris. In 2011, at the ripe old age of 15, she launched Rookie, an online magazine for teenage girls, and began her rise to mini-mogul-dom.

Wittingly or not, Gevinson was anointed a voice—if not the voice—of her generation. In 2012 The New York Times called her “the oracle of girl world,” and she was invited to give a TED talk on the representation of women in film and television. Now 18 and living in her own apartment in Chicago, she is regularly deferred to, sought out, and mic’d up to give her opinions on matters of fashion, feminism, and the heart. But if she’s been overwhelmed by the labels, by the expectations, or by the pressures of her positioning, she’s not showing it. Instead, she seems to be thriving in the spotlight.

Gevinson, it turns out, grew up doing amateur theater and school plays. And, as she demonstrated during a semi-secret performance of Neil Young’s “Heart of Gold” during fashion week in New York in 2012, this voice of her generation can flat out sing. Maybe because of her comfort on stage, she’s been afforded a range of opportunities—like appearing with Julia Louis-Dreyfus and James Gandolfini in writer-director Nicole Holofcener’s charming L.A. comedy Enough Said.

This month Gevinson is taking her talents to Broadway, along with Kieran Culkin and Michael Cera, in a new Steppenwolf production of Kenneth Lonergan’s 1996 comedy This Is Our Youth, in which she plays, according to the playbill, an “anxiously insightful young woman.” During the show’s run in Chicago this July, Gevinson got on the phone with her friend and recent Rookie contributor Claire Boucher, a.k.a. the singer-songwriter extraordinaire Grimes, who was in the studio in Los Angeles, to talk about living on her own for the first time, about playing her age, and life on the stage.

TAVI GEVINSON: Hi! How are you?

CLAIRE BOUCHER: Pretty good. I just woke up. Are you in America right now?

GEVINSON: I’m in Chicago still, but I’m in an apartment. I moved out of my childhood home and I’m closer to the theater now.

BOUCHER: Are you enjoying freedom?

GEVINSON: Oh, yes!

BOUCHER: Did you have a lot of freedom before at your parents’ place?

GEVINSON: I feel like I didn’t necessarily need much freedom. It’s not like I was interested in staying out really late. If my parents ever had to ground me, they didn’t really know what that would mean, because I was inside most of the time anyway. The more abstract version of freedom I’m really enjoying, though. Like, I leave my apartment and I come back and no one touched my shit.

BOUCHER: Are you noticing the thing where it’s like, “Oh, shit, I have to make all my own food. I have to do all this other stuff, and I can’t focus 100 percent on my own stuff anymore”?

GEVINSON: Yes. It makes me understand why someone like James Franco hires people to do everything for him so he can just work all the time. But maybe because it’s still new to me, and somewhat of a novelty, I’m like, “Oh, I get to go buy groceries.” It’s a nice little ritual still. But that’ll probably change as I get older. I was just re-reading your “How to Be a Boss” piece that you wrote for the Rookie book. I was putting parts in my journal because I had to write a really intense e-mail this morning.

BOUCHER: Oh no. Are you okay?

GEVINSON: I’m fine. It’s actually not Rookie related—I don’t find being a boss at Rookie hard because it’s just a coven of people who respect each other and want to be there. But I do find working with people in the entertainment industry hard. As you wrote, it can cause anxiety and depression.

BOUCHER: When an artist, or whomever, moves from their scene to the bigger pond, it starts getting crazy, because all of a sudden people don’t respect you, and you have to start being a lot more aggressive than you would normally be. Which leads to the typical she’s-a-bitch kind of thing. You have to learn to scream at people, which is a really unpleasant thing to do.

GEVINSON: It’s really unpleasant. And I think for a lot of people who are on the business side of the entertainment world, creatives are obstacles. The e-mail that I had to write this morning was basically saying, “I’m fully aware of how valuable I am and how important I am to this project. That should be respected and my needs should be taken seriously. It should not be a given that I do everything you say. So, take that!” I had to wear high heels to have the confidence to write the e-mail. I was sitting in my bed in high heels.

BOUCHER: The worst is when you have to do it in person or on the phone, especially if they cry or you cry. I cry really easily. If I see a butterfly, I’ll practically burst into tears. So it’s really hard for me to yell at people, because I’ll feel so guilty about it. But if I don’t, then they don’t take me seriously and it’s this endless cycle.

GEVINSON: Have you seen the movie Broadcast News [1987]? It is one of my favorites. I got into one of the schools I applied to because of the essay I wrote about Holly Hunter’s character in Broadcast News. She’s the only female producer on this news network and she’s really good at her job, but she allots time in her day to just sit at her desk and cry. And then she’s just back to work. I find that really effective. When I watched that movie, I was like, “That’s how it’s done.” You don’t have to deny the part of yourself that’s emotional. You can confront it, get it out, and continue to kick ass.

BOUCHER: Do you think that, as an artist, you’re more of a collaborator? Because you have a really singular voice. Obviously, you have a brand that’s kind of like your personal brand. And Rookie seems like a very collaborative thing, and then acting is obviously the same. Would you ever make art that was just you?

GEVINSON: I don’t know. Rookie couldn’t work if it were anything but collaborative. If it were just me, then that would be expecting people to identify with me and my experiences, and that’s not really how a website for young women should work. I would like to make a bunch of different kinds of books—writing and otherwise. And with acting, I’m part of this bigger thing and storytelling. I would like to write a movie and, if it wasn’t too crazy, also direct.

BOUCHER: I think when you write and direct, you usually get a more cohesive product. That would be cool, especially because there are so few young female directors and writers. I wanted to ask, do you think the internet is kind of redefining what it is to be a teenager? Because there’s a lot of media that’s aimed at teenagers that other people are getting into. But, conversely, pornography or stuff that’s intended for adults is completely readily available to anyone, like teenagers.

GEVINSON: I think what is really exciting about the internet right now is that, up until now, culture targeted to teenagers was made by adults, and now, when people talk to me about representation—because I gave a TED talk about representation of women on TV and in movies, and then I got asked about it a lot—it doesn’t matter as much as it used to. Before, TV was your lifeline to the outside world if you were a teenager.

BOUCHER: Yeah, there was a monoculture—a few major magazines, a few major TV networks—just a few places you could get media.

GEVINSON: We all have the people we follow on Tumblr whose opinions or taste we respect. And I think because you see so much more variety of opinions and everything on the internet, it’s less decided that something is good or bad. It’s more like we all just sort of like what we like. I really like that aspect of it. It’s super-weird that adults should be dictating what teenagers like in any way, aesthetically or morally.

BOUCHER: I read your essay on Taylor Swift in The Believer. I’m a massive Taylor Swift fan, and I really appreciated it. But I think a lot of the stigma of Taylor Swift comes from the fact that her work is made by a young woman and it’s intended for a primarily young female audience. People refuse to acknowledge that there is anything meaningful or good about it, or assume that it’s inherently low brow because it’s explicitly young and female. A lot of the work you’ve done has been able to bypass this idea. You’ve always had this intellectual, adult thing for your age.

GEVINSON: A lot of people have a knee-jerk reaction that if something is mainstream, then it must not be good. Besides really loving and connecting with her music, I’m just so impressed with the way Taylor has built all of this. And she’s never underestimated her fans or her audience. She’s never ever let anyone think for a second that she isn’t super-grateful.

BOUCHER: The neat thing is it’s smart. The references are smart. To me, it’s adult music. I could see any 40-year-old liking it.

GEVINSON: I could easily talk about Taylor with you forever. I think it’s so well crafted. And even Neil Young endorses the music, not that we need some old guy to tell us if something’s okay—but it does have to do with people thinking it’s dumb, young girl music. Which is frustrating because it kind of waters down all experiences of all young women and says that those experiences are somehow invalid. Sleeping with a guy for the first time can be a big deal for a lot of girls. And it’s really amazing that she kind of tapped into that consciousness and gave all these girls something to relate to and in a way that I think is pretty feminist.

BOUCHER: Is there any feminist dimension to the roles you take, with regards to playing your age or how you’re perceived, and how women in general are perceived?

GEVINSON: I’m not exactly in a position where I get to be super-picky about the roles I get. But I would also never want to be a part of something that I think is poor in taste or doesn’t align with what I believe in. I haven’t given much thought to the age thing yet. There have certainly been parts in the scripts I get for, like, a hooker with a heart of gold or a woman saving a man, as if that’s our job in relationships, and I just don’t even want to fuck with it at all, so I just don’t audition. But with Rookie and with acting, my feminism is just part of how I view the world, so it naturally comes into play. It’s not like I put on my feminist glasses. It’s just kind of naturally there.

BOUCHER: [laughs] I’ve spoken to actors who are like, “Yeah, I always play myself, a slightly different version of myself.” Do you see it that way? Or is it something really distinct from who you are?

GEVINSON: In Enough Said I just wanted to be as natural as possible. I guess I have felt that when I’ve played these parts, it’s just kind of magnifying one side of myself. But I’ve been really happy when friends who saw the play or saw Enough Said have said, “She’s totally different from you!” I see it as an opportunity to feel very free, that everything I’m doing is under the guise of playing someone else. I get to yell a bunch every night, and that’s so therapeutic.

BOUCHER: It must be. Has it been difficult for you to transition to acting? Acting is a really emotional medium, taking someone’s idea and giving a performance of it. And journalism is a lot more intentional.

GEVINSON: Well, I’ve never really felt like a journalist. I’ve felt like a writer and a diarist. I have made myself vulnerable in my writing, and I think that vulnerability makes people strong. My favorite performances or works of art are always people showing that side of themselves. So it was never that hard for me to come to that part of acting. I started acting when I was little. I did community theater and kids programs at professional theaters and plays at school and voice lessons for seven years. I actually stopped when I started Rookie, because Rookie was so time-consuming. But then I realized that I had access to this world where I could go on auditions. And there wasn’t too much of an identity crisis when I started acting professionally because I had been acting longer than I had been writing. It didn’t feel new.

BOUCHER: The play was written in the ’90s, and it’s not obviously a really different time from the ’90s. Is there stuff in it that seems outdated?

GEVINSON: It actually takes place in 1982, but it’s about being young and the time in a person’s life when you’re 18, 19, early twenties, and that stuff feels very universal. The guys in the show are 26 and 31, so they’re looking back and remembering what it was like. Me, I’m in that time, so it requires being maybe a little more self-reflective than I generally am. My friends who are my age and have seen it really relate to it. And that’s such a powerful thing. If I’m having a night where I am not doing well, I’ll imagine that there are Rookie readers in the audience, and I’m like, “Do it for the teen girls!” And that helps, wanting to connect with people and make something that a girl can relate to. I don’t care about men.

BOUCHER: [laughs] You’re working with adults. You have a professional job. You’re a teenager but you’re functionally an adult. Do you feel like a teenager or do you feel like an adult?

GEVINSON: I don’t feel like a teenager anymore, because graduating high school was really emotional for me. I’d obviously made a huge thing out of what that experience was for me, and saying goodbye to it was very weird. So I had to be like, boom, onward and upward. I feel like a young adult. In high school I never felt like my professional life and my personal life were at odds, because Rookie felt like the bridge. Say I was hanging out with people from school and substance abuse was happening and someone takes a picture of me and puts it on the internet. I genuinely felt like that wasn’t contradictory to my job at Rookie because my job has never been to be a role model for young women or teenagers. My only job has been to say that you have to, when you’re in this time, try different things and let yourself become a different person, have experiences.

BOUCHER: It’s important for people not to feel like doing things that are immature, stuff you have to try out when you’re a teenager, is bad, per se. Demonizing it is one of the reasons it becomes such an issue.

GEVINSON: Some of what makes growing up hard for famous kids is that they don’t have room to do that stuff. I was really happy that I could go to school and hang out behind the alley and be somewhat irresponsible.

BOUCHER: Speaking of fame, are you able to walk around? Can you live a normal life?

GEVINSON: I don’t get stopped on the street. If I don’t turn on my computer, this life of mine doesn’t really exist. And if things should get to a point where I can’t go to a restaurant without being stopped, then there are worse problems to have.

BOUCHER: The internet kind of changes where fame starts and ends anyway. Do you know what I mean? There are so many people who are internet-famous. I feel like most people wouldn’t recognize us. But there are these small groups of people who would. And I think there are more people in that weird middle ground of fame than there ever have been.

GEVINSON: I think that’s kind of nice because when people do recognize me, it’s like, “I’m familiar with your writing and your work enough to know what your face looks like.” There’s never this feeling of, “Ugh, this fucking person is in my way.” It’s like, “Oh, that’s so nice. We’re in the same little bubble.”

BOUCHER: Do you read your press? I stopped a couple years ago.

GEVINSON: You stopped? I’ll read something if I liked hanging out with that writer and I’m curious.

BOUCHER: [laughs] I watched Enough Said last night. And James Gandolfini has this insane presence. The minute he stepped in, I was like, whoa. What is it? It’s this really intangible thing. I mean performing in general is … I’ve never seen anyone articulate very well what “it” is.

GEVINSON: When there are people who are really masterful at it, you really want to know how they even get themselves there. Like you’ve said, it’s not like if you’re really good at science, the thing to do is go to a college that’s really good for that.

BOUCHER: Well, you can’t just do a hundred hours of work and get the outcome. With math you can just put your head down, do this much work and get the results. With art, that’s not the case. Sometimes I find not working is the best thing to do for this kind of craft.

GEVINSON: Oh, totally. It’s such a summer-camp cliché, but my best shows truly are when I’m having fun. I know now that the best thing for me isn’t necessarily to sit in my dressing room and get myself there. It’s more to play Mario Kart with the guys backstage, and then they do their scene and I get dressed and I go out there and join them. And we’re just playing.

BOUCHER: I have to be totally alone before I go on stage. I have to get in the zone so I forget about what I’m doing. If I think about it too much and realize what I’m doing, I forget the words. I forget what I have to do. I immediately just fall apart.

GEVINSON: Have you ever been like, “What if I just get drunk?” [laughs]

BOUCHER: For me, it’s fully method acting. It’s really important for me to be in character. Even leading up to the show, I act differently. In real life I’m a lot more bro-y, but when I’m on tour, I wear makeup and stuff; I act like a different person. There’s Grimes, and then there’s Claire. Claire is a producer behind the scenes, and Grimes is this girl who does things that I would never do. It’s a weird situation. But it’s really cool to talk to you. You’re a very smart lady.

GEVINSON: Thank you. I have so much admiration and respect for you, and thank you for everything that you’ve done for Rookie.

BOUCHER: It’s really cool that you’re publishing with Drawn & Quarterly because I worked there when I was 18. Are you still publishing with them for the next one?

GEVINSON: Our third book is actually with Penguin. It was just year three and it was time to kind of start making moves that would help Rookie expand.

BOUCHER: Congrats. It’s very important to be ambitious and not worry about people hating you for being ambitious. I’ve lost many a friend over I-can’t-believe-you-would-sign-to-a-record-label kind of shit.

GEVINSON: Drown out that noise completely. Anyone who thinks it’s somehow dirty or wrong or a moral compromise to be ambitious is, first of all, living in the bad ’90s and, second of all, not a good friend, or not being empathetic or open-minded. I’ve had to shed a lot of that attitude myself because I was such a snob about that stuff when I was younger. And then things become a little more realistic, and you’re like, “Why would I want to hold myself back or be precious?”

BOUCHER: Especially for the kind of thing you do, which is explicitly helpful to young women. And it’s much better for that voice to have a wider audience—if you don’t do it, there will just be more 40-year-old dudes writing for teenage girls.

GEVINSON: One time we did an event, and this girl told us that she found out about Rookie because I did this morning show that I hated doing and I immediately regretted—but it was totally worth it because that’s how she found out about Rookie. She was homeschooled in a really religious household, and in order to come to our event, she had to sneak out during the day, wearing her brother’s shoes, because her parents didn’t let her have sneakers. And then at this event she met all these girls who she became friends with and they all exchanged numbers and everything. And that’s when I’m like, “Why would I try and confine it to a clubhouse. This should be so much more than that.”

CLAIRE BOUCHER IS CURRENTLY WORKING ON HER FOURTH STUDIO ALBUM AS GRIMES, DUE OUT IN EARLY 2015.