Parenthetical Girls Are in a Different Class

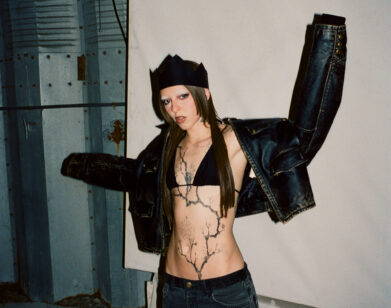

ABOVE: PARENTHETICAL GIRLS. IMAGE COURTESY OF ANGEL CEBALLOS

Zac Pennington is fair, tall, and slender; the bones in his face and hips share a drawn angularity that push gently from underneath his skin. The lead singer and lead creative of Portland band Parenthetical Girls, Pennington is an alternate pop star in the same vein as Kurt Cobain, Morissey, Jarvis Cocker, and Damon Albarn—the sort of musician with an unconventional sexual swagger that necessitates a double take regardless of the onlooker’s sexual orientation.

For the past three years, Parenthetical Girls have been working on Privilege, a musical series released in five parts, an “abridged,” 12-song version of which comes out today. Pennington wrote Privilege from the perspective of various privileged characters, most of whom he admits to finding “despicable.” Although he works hard to avoid the well-worn sentimentality of pop music, it is these occasional sentimental lines, drawn to such an acute and unexpected point, where Pennington really shines. “Try to fit your fingers ’round your waist—piece of cake. Oh, God, you look great,” is found on the closing track, “Weaknesses,” while on opening track “Evelyn McHale” he coos, “train those charms toward the charts, and we’ll be stars just the way that we are.” With songs like these, we’re inclined to agree.

In anticipation of Parenthetical Girls’ latest release, Pennington was kind enough to give us a few words on Privilege.

RYANN DONNELLY: Did you grow up around privilege?

ZAC PENNINGTON: Not at all. My interest in privilege is based in an outsider’s disdain-slash-romanticism of what privilege is. Growing up, I had a lot of class disdain that, over the course of my adult life, I’ve come to grapple with a bit more, and feel a little more—ambivalence might not be the right word—but like everything, when you get older, things become less concrete. Things become more gray. I still think that, in writing about privilege, I wrote about the most despicable aspects of it, I guess. And, I really enjoyed writing from the point of view of like a Scrooge McDuck privilege-type person—this sort of cartoonish idea of privilege.

DONNELLY: Is there a particular song you wrote from that perspective?

PENNINGTON: There are a handful of these songs that are written from the perspective of several characters. There was a series of these songs on the box set that were part of this “privilege” family, and they all kind of ended up on the real album. The songs “The Common Touch” and “Sympathy for Spastics” are both written from the point of view of a very despicable character about the imagined sexual politics of privilege—how relating to someone of a distinctly lower class than you in a sexual fashion, or a corporal way—how there’s a dehumanizing element. Like, “The Common Touch” is about class conquest, and then “Sympathy for Spastics” is about a weird, liberal privilege, which, from my perspective is way more despicable: people who are insanely privileged and acknowledge it, and try and fail miserably to relate to people of lower classes.

DONNELLY: Were these characters from real life, or were they fictional?

PENNINGTON: They’re wholly fictional. I feel like they’re all incredibly reductive. I really like writing villains. I don’t like writing sympathetic characters, because I get self-conscious about writing sympathetic characters.

DONNELLY: Do you feel like it is easier to create a character that is unlikable?

PENNINGTON: For me it is, because I made a conscious decision when I started writing music that I wanted to write about things that other people weren’t writing about. It felt like there was no point in contributing to the larger pop music canon if I was doing the same thing as everyone else. And, I really dislike the bulk of sensitive singer/songwriter types. Everybody I really love is that character, but it’s harder to hit that sweet spot.

DONNELLY: What else was influencing this approach?

PENNINGTON: Honestly, a lot of this came from re-visiting a lot of records from when I was a kid. Like, northern British pop music. Pulp is a really good example. I, one of many millions, re-discovered Pulp and listened to their Different Class record, and felt a much different perspective on it from when I was a kid. “Common People” is maybe my favorite song—I don’t know, top five faves. I don’t really like political music usually, but the kind of political music that I like is all about personal politics. Ideologically, I really got into the riot-grrrl movement, but there were very few riot-grrrl bands that I identified with, because they were all just so overtly political. Huggybear I really liked, because it was more about personal politics.

DONNELLY: Do you feel privileged?

PENNINGTON: Oh, always. I am an incredibly privileged person. I am able to make a very laughable living making music, which feels incredibly privileged. I am like, a straight, white male, which has its own thing. I feel privileged in those ways that are more abstract than monetary privilege, and more often are more interesting, and more important than monetary privilege. But it’s harder to talk about.

DONNELLY: How do you separate the affect of privilege, and the affect of pretension? Both can be alienating or elitist and exclusive.

PENNINGTON: My revulsion toward social privilege is, of course, driven in part by not-so-dormant attraction to its effects. This is something I imagine you can sympathize with. I’m curious about it the way that I’m curious about sociopathy and serial murder: it’s all very romantic in its obliquely alien way. I’ll never fully understand it. Though I haven’t really thought much about it; I suppose the separation for me between privilege and pretension is maybe similar to the nature/nurture dichotomy. The affects that I think of as projecting pretension are, for the most part, the result of free will—a choice a person makes and can unmake.

Pop music—especially independent pop music—is kind of a strange world unto itself when it comes to claims of pretension. For a medium that’s all about affects and archetypes, there’s a weirdly puritanical fanaticism about “authenticity”—it revels in its own delusional ideas about honesty and egalitarianism. To me, affecting the role of the earnest singer-songwriter or the juvenile nihilist is just as disingenuous, performative, and innately pretentious as anything that we do—the minute anyone decides to take to a stage, it’s all a form of play-acting. This is all tied to class as well, I think—pop music as the music of the people is mostly meant to perform as such, fetishizing the noble poor and their homespun simplicity. Music and musicians with interests and intentions outside of these confines are usually suspect—they’re self-important, self-serious, assholes. What’s characterized as “pretension” in pop music hits the same gag reflex as privilege, because they’re both seen to aspire to a kind of elitism that’s totally counter to pop ideals. I’m happy to own being labeled pretentious though, because I’m called pretentious for choices I’ve deliberately made, rather than who I inherently am.

DONNELLY: Can you address the visuals you’ve made for the record? There seems to be a perpetual motion to the videos, and some of these elements are repeated in your live performance.

PENNINGTON: Nothing is actively choreographed live. It’s all pretty random. I have go-tos in performance, but it’s all based on environment. The environment always informs how a performance goes. I hadn’t thought about that, though; there is a perpetual motion to the imagery for the album. I hadn’t put that together. To Allie [Hankins’] credit, she has co-art directed a lot of these videos with me. And, so I think that sensibility has informed it for sure. And, obviously in the video for “The Common Touch,” because she choreographed that whole piece. She did a lot of the choreography in “Careful Who You Dance With.” I’m also kind of a cinephile, and tracking shots have always been my soft spot—I love stuff like that. Tarkovsky tracking shots are my dream world.

DONNELLY: Can you talk about the idea for “Curtains”?

PENNINGTON: “Curtains” the song is a eulogy—a eulogy for Privilege, and in many ways a eulogy for Parenthetical Girls. I wanted to present a literal, visual counterpart with the video, and as I’ve got something of an obsession the ceremony of death, I’m always looking for new, narcissistic ways of performing my own. Initially I wanted to have a public hanging, but figured a Viking funeral would be more cost-effective… I just had to buy a boat.

DONNELLY: You also made some commercials for the abridged record, right?

PENNINGTON: We did a series of advertisements in the style of old Calvin Klein television ads. The impetus felt a bit cynical, but after we made them, we realized there isn’t really a place for them. They’re not cynical things, because they can’t really be. It occurred to us that there is no place for them to go. No one knows what to do with them. I really enjoyed that process of making them—just a loving homage. I transferred them to VHS tape, and then transferred them back, and its funny because the way that I relate to them is through someone taping them off their television in 1982, or whatever, and putting them on the Internet. So, the aesthetic of them is a weirdly modern aesthetic, because it’s post-several layers of recapitulation. So, part of the homage is an homage to the medium of having recorded and then reposted on the internet, and then we did that again. I don’t even know what those look like without VHS squiggles.

DONNELLY: What will you be working on next? Are the concepts as rigid as Privilege?

PENNINGTON: I’m presently in the process of writing some new material, but it’s too soon to tell just how it’s going to take shape. Privilege was a bit of a purge, and it’s been a challenge—as it always is, I suppose—to know exactly how to begin again.

PRIVILEGE IS OUT NOW. FOR MORE ON PARENTHETICAL GIRLS, VISIT THEIR WEBSITE.