The Seduction of Night Works

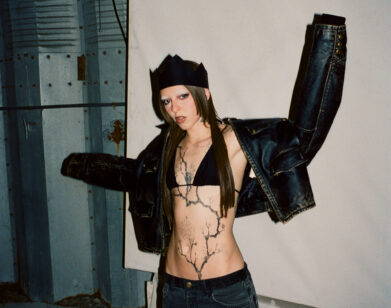

ABOVE: GABRIEL STEBBING, AKA NIGHT WORKS. IMAGE COURTESY OF PERRY CURTIES

A tale involving the twists and turns of longing and high stakes drives Urban Heat Island, the debut album from Night Works (moniker of Gabriel Stebbing). With his new project, Stebbing (formerly of Metronomy and Your Twenties) proves that he has not abandoned catchy pop riffs, but has instead cast them into the night, where disco-tinged beats, R&B bass lines, and elegant piano loops form the soundtrack to a reality populated by characters existing on the edge of uncertainty.

With Night Works, Stebbing has created an alluring mix of tracks capturing that moment between dusk and dawn when adrenaline rises before a post-rush come down. Taking inspiration from the Wall Street crash of the ’80s, the books of Jay McInerney, and time spent in London, Stebbing shapes an irresistible world in which partygoers lose themselves while slipping from room to room, savoring every deliciously melodic moment.

We spoke with Stebbing by telephone, where from London he talked about his new album, Chaka Khan, and why we shouldn’t expect him to make a rap record.

J.L. SIRISUK: There was a bit of a gap between leaving Your Twenties and embarking on this new project. Can you tell me what happened during that time creatively and how Night Works came about?

GABRIEL STEBBING: Night Works kind of emerged from the dissolving of Your Twenties. I started making a Your Twenties album with my friend Joseph Mount from Metronomy producing it, and as the live band kind of evaporated and everybody went to separate projects, I carried on making this record. By the time we had done a dozen songs, it was clear that the last three were sounding really, really different. They weren’t sounding like Your Twenties songs, which were kind of these little sharp, three-minute pop songs. The sound was starting to really expand, and the first moment that it hit me that I was no longer making Your Twenties music was when we made “Long Forgotten Boy”—it became the first song of the new album but I didn’t know it at the time. I spent a year making a Your Twenties album, scrapped it, and then just followed this new sound for another year.

SIRISUK: Since “Long Forgotten Boy” was the first song you recorded for the album, did it kind of set the tone? Did you come up with a concept for the album after that song or did you approach it track by track?

STEBBING: I like to say that it’s kind of like a little acorn, or the seed that the album grew out of. “Long Forgotten Boy” is a song about losing your mind, about this 4 am or 5 am moment when you’ve reached the end of the night—not just reaching the end of the night, but you’re reaching the end of an era or something in your mind and feeling a bit washed up. So, in a way, it was a little bit autobiographical, after putting so much time into the Your Twenties stuff. But the general shape of the song having this feeling of redemption was something that definitely came like a template for the rest of the album. I knew that the songs were mining this territory that was a little bit deeper, and also I became fascinated by the idea of people who are living close to the wire. Whether it was to do with people working or all this stuff with the financial crash, it really affected me. I became invested in this idea of a kind of psychosis and a kind of redemption somehow. It had all of that DNA for the rest of the album.

SIRISUK: It does feel like there are numerous types of characters that populate the album. Do you feel the record should be listened to in sequence?

STEBBING: I was thinking about characters during the writing, but it was almost a way of dividing myself up. They all have little bits of me and bits of people I’ve met, so it was a way of breaking down different facets of myself and things I wanted to express. In terms of listening to the album in sequence, it wasn’t like I sat down and decided I was going to write a concept album that has a story of all these characters in sequence. Once the songs were kind of getting towards being finished, it became clear that I wanted to have a night and day, or a dusk ’til dawn, kind of arc and that maybe if I put some of the more pop songs or up tracks in the beginning the album, it might fade or dissolve into something that’s a bit more reflective. I guess I still think of it in terms of vinyl and turning over the record halfway. You’ve got an early evening side, and a nighttime side.

SIRISUK: I was really excited to see the videos released in advance of the album and they were all directed by Daniel Brereton. How did the two of you come together to work on the series of videos?

STEBBING: I actually met Daniel when I was in Metronomy, and he directed three videos which were on Metronomy’s second album, Nights Out. He directed “Holiday,” “Heartbreaker” and “Radio Ladio,” and I’d always wanted to work with him again, because I think he has a really unique visual style. He likes to develop ideas with the artists from the start. It was natural we’d get together to make a video. We made “I Tried So Hard” for no money at all. I had a really simple idea of the slow pan into close-up of the guy who is getting sweatier and sweatier. It was really fun to do and kind of exciting to get to work with one person for a whole series, and I don’t know if that kind of thing happens often.

SIRISUK: Are there any films or books that influenced the imagery?

STEBBING: In “Modern European,” it was easy because we were giving all these nods to French New Wave filmmaking, but in a very gentle, cheeky fun kind of way. There were nods to The Red Balloon and Jean-Luc Godard, people kissing in the street, that kind of thing. In terms of the other vides and the album as a whole, I was reading this New York author called McInerney who is kind of contemporary of Bret Easton Ellis. He wrote Bright Lights, Big City and Brightness Falls, which are novels about the 1980s Wall Street crash. It’s not American Psycho, it doesn’t go that deep into psychosis, but it’s actually more about the texture of New York City around that time, and that was a big influence on making the record. In terms of the videos, I knew what I wanted to have. For instance, in “I Tried So Hard,” I wanted the colors to look really washy, like an old Top of the Pops performance from the 1980s.

SIRISUK: You mentioned Top of the Pops. I was listening to “Share the Weather” and thought it sounded a bit like Prince infused with a bit of Chaka Khan. Is that you rapping at the end of the song?

STEBBING: [laughs] No, it’s not me, don’t worry, but the guy who’s rapping, you should watch out—I think in a couple of days, there will be a unveiling on the Internet of the guy who is rapping. He’s a guy called Roman—he’s a London artist. He’s a friend of mine, but he’s a real enigma. It’s funny, because Share the Weather came out of messing around in the studio and trying to come up with a chorus for one of his tracks and it mutated into this song. There’s this station in London when I was growing up called Capital FM and it played all the artists you just mentioned, like Chaka Khan. It was pretty middle-of-road but constantly seemed to be on in my house, because that’s what my older brother listened to. I think “Share the Weather” is the most self-consciously fun track on the record, in some ways.

SIRISUK: For a second I thought maybe it was you rapping, and I wondered if your next album was going to be a rap album. [laughs]

STEBBING: [laughs] I can say exclusively that my next album won’t be a rap album. I’m not good at it, that’s the only reason.

SIRISUK: After having been in two bands, how do you feel now that the focus has shifted to your own vision? How is it different?

STEBBING: I think I’ve had some very different experiences of being in bands over the years. Metronomy was Joe Mount’s project; although he’s always had a band backing him up, he’s always written and produced it all. And Your Twenties was a bit more collaborative and was me trying to recreate the band I had when I was a teenager. Night Works, I’ve got to say, is a new experience for me. Its success or otherwise boils down to my confidence and my motivation and how obsessed I am with it, which I guess is completely all-consuming and really great because it appeals to the control-freak element of me. I would be lying if I said it was great the whole time, because I think I’m having to draw on parts of myself that I didn’t really know I have, or that I still don’t know whether I have. There were times when I was making the Night Works album when I thought I couldn’t continue and I just had to stop, and it was all bound to my shifting levels of self-confidence, which aren’t always that high. But having said all that, it’s amazing to just be able to make the kind of music that I’ve always wanted.

SIRISUK: With Night Works, what kind of experience do you want people to take away from it?

STEBBING: What I’m always aiming for is to keep the communication as direct as possible. To leave some part of that experience so that when people listen to it, they share it and understand it, or they bring their own thing to it. I think as a musician and as a writer, you’re just trying to constantly connect. If the listener ends up enjoying it, is touched by it, or thinks a little bit because of it, then that makes me overwhelmingly happy, because that’s the only reason I’m doing it, really.

URBAN HEAT ISLAND IS OUT NOW. FOR MORE ON NIGHT WORKS, VISIT HIS FACEBOOK PAGE.