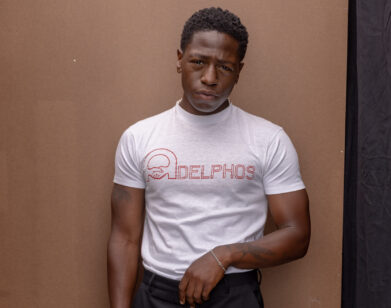

Diego Ongaro Among the Trees

Gangsta rap, golf, livestock, and logging form the understated backbone of Bob and the Trees, director Diego Ongaro’s debut feature film based on his 2011 short of the same title. Seven years ago, the director—who had been working on short films and commercial projects in his native France and then New York—moved to the Berkshires in Western Massachusetts with his wife, novelist Courtney Maum, in order to escape the grind and the high cost of living in New York City. The couple acquired a “fixer-upper” home (Ongaro, an amateur carpenter, has just finished renovating their house, eight years on), and Ongaro soon met Bob Tarasuk, a middle-aged career logger with a penchant for Immortal Technique (whose track “Point of No Return” features in Bob and the Trees, both short and long) and a strong 9-iron. They hit it off, due in part to their shared affection for political rap, and Ongaro approached his new friend about making a partially biographical short, a snapshot of the life of a New England logger. The resulting films feature Tarasuk as the titular Bob, surrounded by a cast of locals also playing fictionalized versions of themselves. (The sole exception is Polly MacIntyre, a Philadelphia-based actor who plays Bob’s wife.)

“What drew me to make the film was the person … sort of my muse,” Ongaro says. “I think he represents a kind of American man that you don’t see very often in movies, a really blue-collar, extremely likeable, hardworking guy, and as genuine as you can get.” He sets up his fictional Bob as a contemporary Sisyphus, forever rolling his stone—or his tree trunk, as the case may be—up the mountain, only to see it roll back down again. Bob and the Trees opens on a particularly harsh Massachusetts winter (its short-movie predecessor plays out during a mild spring). A case of rabies down the road prompts Bob’s neighbors to slaughter all their animals, or else close their farm under quarantine for six months; one of his own cows then shows up with a suspicious gaping puncture in her neck. He purchases a plot of land to clear, only to find the trees have been hollowed out by ant colonies and cannot be sold for wood.

Ongaro confesses that his own experience has also made its way into the movie. He urged Tarasuk to ride a moped in one scene, Tarasuk resisting vehemently, and Ongaro’s wife Maum’s (also his Bob and the Trees co-writer) debut novel I Am Having So Much Fun Here Without You appears in one bedroom scene. Though they share a title and characters, Bob and the Trees‘ short and long forms bear little resemblance to each other. Ongaro describes the 2011 film as a “slice of life,” “contemplative,” and evocative of a larger story to come. When the short played well, Ongaro says he realized there was still more to say about Bob and the Berkshires. So he set to work crafting a follow-up, his first feature-length film.

Bob and the Trees premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, and while the director has settled back in at home in the Berkshires, the film continues to make rounds. It will next screen at the Museum of Modern Art Dec. 12 and 14. We spoke with Ongaro over the phone while his two-year-old daughter napped (he says much of his free time is now occupied by fatherly duties), and we discussed Sergio Leone, sledding during a blizzard, and the sometimes indistinct boundary between fiction and documentary.

KATHERINE CUSUMANO: You made this movie after becoming friends with Bob—what were the challenges of depicting somebody that you’re close with in real life?

DIEGO ONGARO: The toughest challenges for me making this film was to break myself from the real Bob and the fictionalized Bob. Trying to find the right story, the right script, was the hardest in the process of making this film. I worked with my wife, who’s a novelist. She writes fiction novels, and first of all, it’s hard to work with your wife. [Laughs] She was very much drawn into creating a plot, where I was more into being free from a plot and allowing life to happen in front of your eyes. I was aware that we needed a strong backbone for the film to tell a story that people engage in, but I also really wanted to be as realistic, credible, and genuine as possible. So finding that right balance between the stories that will make you want to see more because there are stakes, there are pressures applied to characters, and at the same time, something where you see life unfold in small moments that don’t really relate to any kind of plot. It was hard to find a balance—the story is a lot inspired from who Bob is in real life and from events that happened in Bob’s life. It was hard to stray into fiction, so it was about allowing myself and ourselves as storytellers to be able to do that.

CUSUMANO: Do you think there’s something that you can say with fiction that you can’t necessarily in documentary?

ONGARO: [pauses] I don’t know. I have never thought about it this way. The reason I wanted to create a fiction is that, first of all, I like to be in control of what I’m filming. Not complete control—I like to allow also life to interact, and so it’s kind of a sort of a balance between doc and fiction—but I like to be in control; I like to know where the story’s going and be able to wrap my head around it. In documentary, it’s super exciting because you don’t know where the story is going, but you could be filming and doing it for years and years, It was also a challenge—is this going to be Bob’s film? Am I going to be able to do that with this man that is my friend? Can I tell the story that is sort of universal and is going to appeal to people? But it’s always important to me not to be able to see the invisible hand telling the story. It’s really important to be drawn into it as if you could be watching a documentary. I’m not trying to trick people—it’s pretty clear—but I like to think of it.

CUSUMANO: How much was scripted before you started shooting? I’m thinking of the scene in the bar in particular, when Bob goes up to the guy who sold him the land and says, “Did you know that this was an ant farm?” That scene was so uncomfortable. There was that awkwardness of, ‘we’re friends,’ and ‘we have this contract.’

ONGARO: None of it was scripted. We worked from a treatment, so every scene was written ahead of time, but it was written more like a couple paragraphs per scene, which describe in details what happens in the scene. As far as dialogue, there were a few indications, sometimes a sentence. It was really important to me to not put any of my words in these people’s mouths. I wanted to use their own words because they were cast for who they are in real life. That bar scene that you were talking about, we did a few rehearsals a few weeks ahead of time, and it was instantaneous. We just had to put people in the bar and get Bob upset and get him into the story and it worked perfectly. It was a really strong scene, and it was interesting to see how Bob was affected every time he left the bar. He was dreading getting back in there because he knows so many of these people and he was just creating such a scene. It was hard sometimes for people to see what was real and what was not real.

CUSUMANO: Was that easier or harder, working with non-professional actors, balancing real life versus character?

ONGARO: Sometimes it can be harder because you can’t ask people to do specific things or go into a specific direction. They’re just not going to be able to do it. Someone like Bob has to be himself. He’s not going to be able to just do something on command. But he’s really good at being himself. Some of it was wonderful —some of it, we just had to do one take and everything would be so natural and that you could move on—and some of it was harder. I was really careful to not go too far from the characters. I know who they are, or not. You really have to know the people you’re working with, to know what are your limits. A lot of scenes we shot almost like a documentary, like when they’re logging in the woods. These guys are loggers professionally. Some scenes it was more plot-orientated—something you need to happen where you really need to be more in control. Sometimes it was harder to get what you needed. But the fact that things are not scripted allows for a lot of surprises. You end up with something different from what you thought you had and it can be really great.

CUSUMANO: How did it change? What ended up different?

ONGARO: We got stuck in a blizzard, and we couldn’t go anywhere so we decided to just pack the sled and go to the beautiful hill close by where Bob lives. It was a really cool scene that wasn’t planned. Bob and his son in the film go sledding and it’s a complete white-out. It’s a really nice father-and-son moment, where Bob ended up head-first in the snow. Little things like that were great. As far as the result, I was blown away by the performance they could do. They never thought they could be so intense and powerful. Some of the argument scenes, they had to hug each other after the end because they were screaming at each other, and they know each other in real life and it felt so real.

CUSUMANO: What in general inspires you to make a movie?

ONGARO: Right now it’s two things: It’s characters, and the way I was drawn into making this film was with Bob, and a sense of place, really discovering a new place and traveling. I love films that are set in South American countries that I’ve never been to or in Eastern Europe or in Siberia. You get to enter a community and really see life.

CUSUMANO: Did you ever envision yourself doing feature-length films? Bob and the Trees is your first feature—did you ever think of moving from short films to features?

ONGARO: It’s always been the goal. I have to say, it was terrifying to move from the short films to the bigger films. It was intimidating. It felt like this massive mountain. But that’s always been the goal. I grew up watching films, mostly westerns, and making films is always what I’ve wanted to do.

CUSUMANO: When did you know that you wanted to make movies?

ONGARO: I was a teenager. I was fed classic westerns all my childhood, like John Wayne, John Ford, all these great westerns. The myth of America was something that really appealed to me, so I guess it’s not a coincidence that I now live in the U.S. and I’m really drawn to the country and the open spaces. The big shock to me has been switching from classical westerns to Sergio Leone and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, or A Fistful of Dollars and A Fistful of Dynamite, which completely retold the western stories in a completely different way, from a very strong point of view. It was amazing. I was super young, but it was a trigger.

CUSUMANO: How has your taste in what you watch changed?

ONGARO: I don’t see many westerns anymore. It evolves with time. I went through a phase of watching very auteur French films, independent films from the U.S. or from the rest of the world. I watch less and less blockbusters. We watch a lot of things, especially since we live in the woods. There’s not that many things to do at night, so we do see movies. I really like the Dardenne brothers. I saw Carol, great movie, really impressed me. 45 Years with Charlotte Rampling was amazing. Something that inspired me to make Bob and the Trees was this film called Ballast by Lance Hammer. He uses non-professional actors in a very specific way. It’s a bleak, bad story, but the way he tells the story is really subtle and beautiful at the same time.

BOB AND THE TREES WILL SCREEN ON SATURDAY, DECEMBER 12, AND MONDAY, DECEMBER 14 AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART IN NEW YORK CITY.