The Tarantino Actor

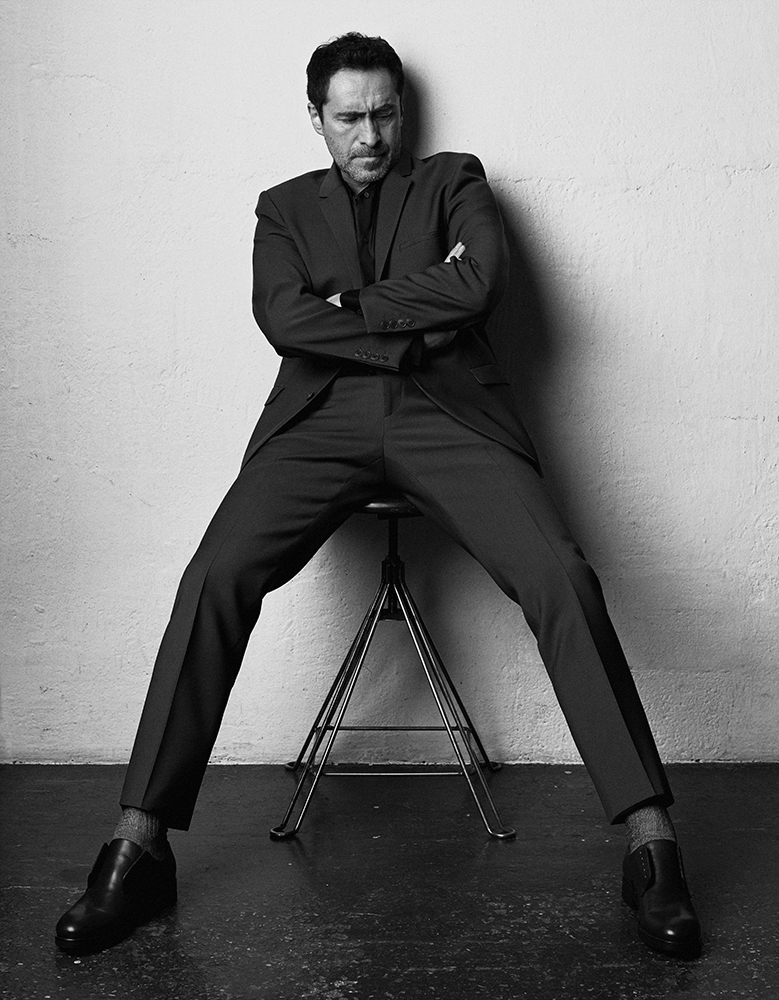

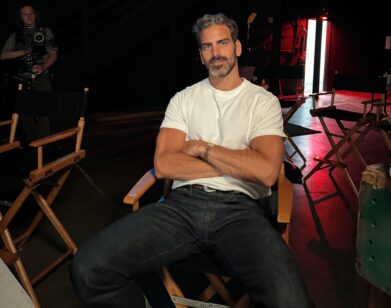

DEMIÁN BICHIR IN NEW YORK, DECEMBER 2015. PHOTOS: MICHAEL SCHWARTZ/DE FACTO INC. STYLING: ANGELA ESTEBAN LIBRERO. GROOMING: NATE ROSENKRANZ/HONEY ARTISTS USING ALTERNA HAIR CARE. PHOTO ASSISTANT: NATHAN MARTIN. STYLING ASSISTANT: MAR PEIDRO. DIGITAL TECHNICIAN: KATIE HAWTHORNE. SPECIAL THANKS: FAST ASHLEYS.

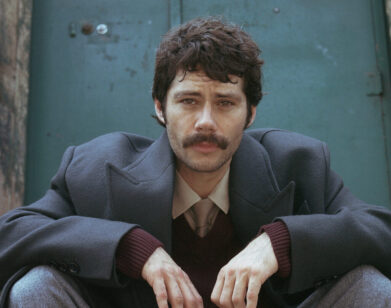

The 70mm print of Quentin Tarantino’s latest feature The Hateful Eight quivers slightly on the screen. The film opens with a few leisurely shots of the frosty southwest, lingering just long enough to remind audiences that this will be a three-hour odyssey with an intermission. Then it introduces two bounty hunters played by Samuel L. Jackson and Kurt Russell, and the saga begins. Russell’s character, known colloquially as “the hangman,” is transporting Daisy Domergue (Jennifer Jason Leigh), a prisoner worth a bounty of $10,000 for an unspoken crime, across the frozen landscape in order to see her hanged in the nearby town of Red Rock. They’re sidelined by a sudden blizzard at Minnie’s Haberdashery (not really a haberdashery), where they encounter Demián Bichir‘s Bob the Mexican, a mysterious figure purporting to take care of the haberdashery in its proprietor Minnie’s absence. Minnie has gone to visit family, he says. But someone among this cloistered cast of characters—Tim Roth, Michael Madsen, Bruce Dern, and Walton Goggins round out the eight trapped at Minnie’s by the looming storm—is lying. It’s a peculiar hybrid of Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None and Tarantino’s own Reservoir Dogs, with nods to golden-age westerns for good measure.

For Bichir, this role is the culmination of a long-standing ambition to work alongside Tarantino, an achievement that stands out even in a career that has spanned multiple countries and performance media. When we speak with Bichir prior to The Hateful Eight‘s release, he’s fresh off his most recent theater run back in Mexico, a production of The Police by SÅ?awomir Mrożek directed by his father Alejandro and co-starring his brothers Bruno and Odiseo. He eagerly pulls out his phone to show off a backstage shot. “This is my dad right here,” he points out. “My older brother, my younger brother.” Then, referring to the opportunity to work with family, “It’s just a bizarre type of surreal world.” Though he grew up in a showbiz household, and he and his brothers have frequently come up for the same roles, he quickly denies any competition within his family. “When you fight for a role,” he explains, “I think the biggest disappointment is that that role ends up in the wrong hands.” No individual actor can play all the roles: “When that role that I want very much lands in an actor’s hands, I’m the first one to celebrate,” Bichir says. “If that actor happens to be my brother, then it’s a double celebration.”

In addition to The Hateful Eight, Bichir also just wrapped his first feature as a writer, director, and actor. Titled Refugio, the film co-stars Eva Longoria, Jorge Perugorría, and Jason Patric. (When Interview last spoke with Bichir, he had just begun work on his film as well as Robert Rodriguez’s Machete Kills—more on that later.) In person, Bichir is ebullient; he’s in great cheer when we sit down in Brooklyn immediately following a photo shoot. He pauses periodically throughout our conversation, bidding farewell to the shoot’s crew or bookmarking a thought to take a selfie with a new friend and returning to pick up exactly where he left off. We discuss his lifelong adulation for Tarantino, co-stars Roth and Jackson, and his not-so-secret soccer aspirations.

KATHERINE CUSUMANO: To start, I want to ask you how you got involved with Hateful Eight. How did you sign onto the role?

DEMIÁN BICHIR: I did The Hateful Eight because of Robert Rodriguez. Robert Rodriguez and I were shooting a film together called Machete Kills, and every day we were shooting, he insisted that I was a Tarantino actor. He would tell me that every day: “Oh, man, you’re such a Tarantino actor.” I said, “Okay, let’s make a deal—stop saying that to me, and please tell Quentin that.” And he did.

When I met Quentin, he told me what every actor wishes from any director. He said, “I’ve been through a Demián Bichir marathon. I’ve watched everything you’ve done.” Most of the time, they don’t even know what you’ve done. Then he said, “Listen, I’m working on this new draft. When I get it ready, can I send it over to you?” I said, “Please. I beg you. I will be ready to read whenever you are.” He said, “No, if you like it, it’s yours.”

CUSUMANO: Being on set among actors who are already very much defined by being “Tarantino actors,” like Tim Roth, Michael Madsen, and Samuel L. Jackson, did you feel like the newcomer among them?

BICHIR: I did right before I went in in May and met with everyone. That was the first time we had this table reading. I was curious to see how those big names would react. They don’t really know anything about you. You had to show your own credentials, and it could be hard and intimidating if they weren’t the way they are—these guys are so generous. They embrace you. Can you imagine saying ‘Hi’ to Sam Jackson and he goes and gives you a hug? It’s like being hugged by a lion. They know that if you are there, it’s because of a reason. They don’t need any test; you are already there. And we’re still this family that was created. It’s like playing soccer with Barcelona, like being on the same field with all these big players. Instead of being afraid of playing with them, you bring the best of your game. It’s encouraging. They invite you to play your best.

CUSUMANO: What do you do to prepare for a role?

BICHIR: You go through different processes. I think the first one is a deep state of fear. It always happens to me whenever I do a new project—I don’t even want to touch it. I don’t want to dive into it because I know that once I’m into it, there’s not safety net. I go deep, all the way down. So there’s this phase first where you have to deal with your own demons. You don’t know what to do with a character. Then, of course, you need to know geographically where you are, what year you’re playing, what’s happening politically. Everything else is agreement between you and your director. I’m an actor who’s accustomed to bringing a lot of stuff to the table, and you have to be ready because some of them will be accepted and some of them will be rejected. Then you need a generous, free, fearless, loving director like Tarantino to allow you to take those risks.

CUSUMANO: When you’re directing your own movie, you have an additional layer of removing that safety net. You’re both the lead actor and ultimately the last person accountable in a production. What was it like being the lead actor in your first directing project?

BICHIR: [laughs] It turned out to be a lot easier than I thought. I’ve been doing this for more than 40 years and I pay attention. I open my eyes and my ears, and that’s why I work. A lot of the things that I’ve learned in the past have been from dear friends. Rodriguez’s favorite line is “Fácil!” Easy! He makes things easy. He doesn’t complicate his life. He’s obsessed with perfection, but he makes it easy, and that’s pretty much the way I work as an actor. You will find complications, and when that happens, then you deal with it. Don’t complicate whatever is not complicated.

CUSUMANO: Before Robert Rodriguez started telling you that you’re such a Tarantino actor, was Tarantino on your list of directors you wanted to work with?

BICHIR: Not only in my list of directors that I wanted to work with, but on my list of directors who marked who I am as an actor. He’s done many of the films that made me fall in love with this. I think I’ve seen them all. You, as an actor, are defined by those things too. I am defined also by Woody Allen’s films and Martin Scorsese and Jim Jarmusch and Julian Schnabel or Almodóvar, or by Guillermo del Toro, Iñárritu, Cuarón. Even if we haven’t worked with them, we are all defined by their filmography. So Quentin was that way before I even dreamt of being a “Tarantino actor.” When I saw Reservoir Dogs, Iwanted to dress like those guys. Jackie Brown is one of my favorite films. I love that people don’t pay too much attention to Jackie Brown. Or, for example, Natural Born Killers—that’s a Tarantino script. I think he should have directed that. He’s an amazing filmmaker, but his stories, his scripts, they sing. They’re like a symphony. They have this musicality, this rhythm. All you have to do is say the lines properly.

CUSUMANO: One of the things that I found really striking about it, and I think Tarantino does this very effectively in Django Unchained as well, is it talks about some really serious themes of politics and xenophobia—

BICHIR: —and racism.

CUSUMANO: In a really humorous way. Right. And it’s coming out now, at a moment when American xenophobia is at a high once again, and it takes place in an era when that was also the case. What do you think the resonance is of that today?

BICHIR: A lot of people love Tarantino’s films because they’re spectacular, they’re beautiful, they’re wonderful. He hires the best group of artists—not only actors, but everyone around: best photographers, best set designers, best production designers, costume designers. A lot of people love his films because they’re bloody, they’re gory, they’re savage. But very few people see that he’s a very political director. The last two films, especially this, we’re talking about the end of the Civil War. We’re talking about things that we talk about now.

CUSUMANO: Right, 150 years later.

BICHIR: Very little things have changed. We’re still discussing those things. That’s what he does ingeniously. He’s bringing to the screen issues and substance and matters that we all have to face and talk about and discuss. Even the immigration issue is there somehow, too. All of this has to do with the way you hate your neighbor because he’s different. [Samuel L. Jackson’s character] says, “Minnie used to have a sign here that said, ‘No dogs or Mexicans allowed.’ You know why she took it off? Because she started allowing dogs.” Now you see all the xenophobia against Mexicans commanded by this moron Donald Trump. He’s lying to the American people, but not only that—there are a lot of people who think the same way who have real power. We need to stop saying we don’t want those guys here, but we need them. You have to make up your mind. You can’t play this double morality type of game. Just not my gardener, not my maid, not my nanny, and not my cook—the rest of them, send them back. Send them back where? This is home, where you have your kids, where you have your house, everything that your life represents. So it’s important that people like Tarantino talk about every single thing. We all have to raise our voice and talk about it.

CUSUMANO: What is next for you?

BICHIR: One of my dreams is to become sufficiently famous that I can play this charity match that happens every year or two with celebrities at Old Trafford, at the house of Manchester United. Sometimes I think I just want to be famous so they can call me to play that game. I’ve been submitting my name forever and every time they still don’t think I can sell a ticket or two. I want to be a household name so they can invite me to play that fucking game before I become 80. I still can play!

THE HATEFUL EIGHT IS OUT NOW.