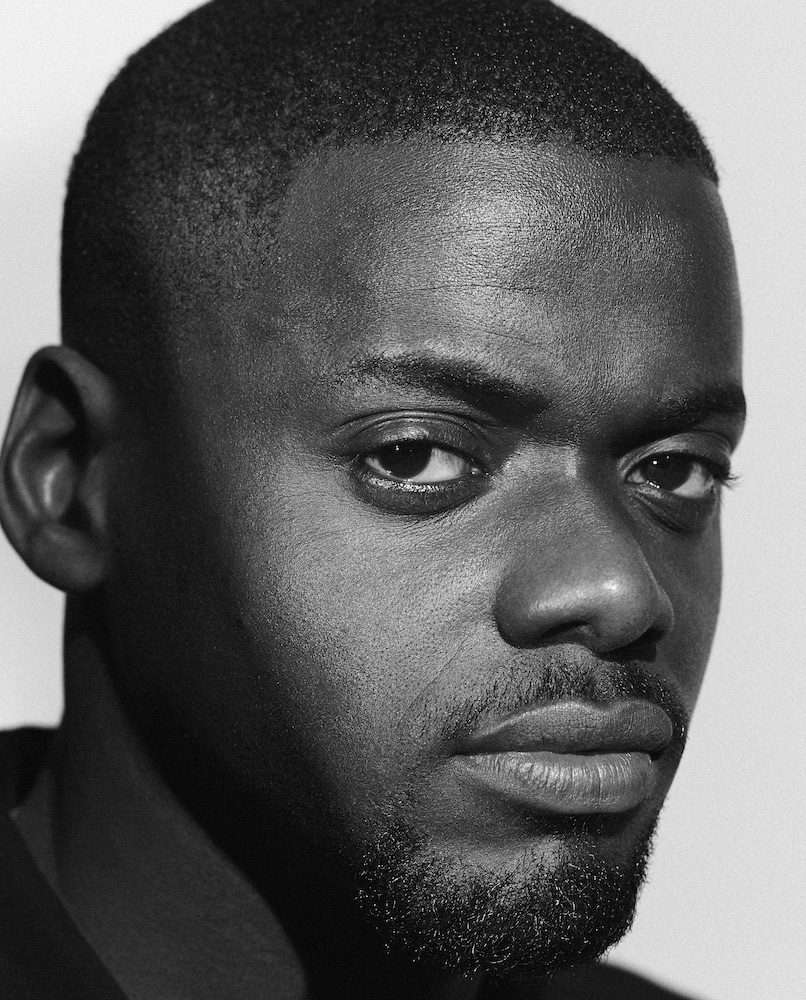

Daniel Kaluuya’s Next Move

DANIEL KALUUYA IN LONDON, NOVEMBER 2016. PHOTOS: JASON HETHERINGTON/SERLIN ASSOCIATES. STYLING: TANJA MARTIN. GROOMING: VICTORIA BOND/CAREN USING BURBERRY BEAUTY.

Daniel Kaluuya never went to university. Instead, the 27-year-old North London native joined the British youth drama Skins as a writer and actor when he was still in his teens. “Skins was like our uni,” he explains. “I’m tight with everyone from Skins because we had that special experience together. We always meet up, always go to dinner, always have Christmas dinner. Everyone’s started having kids now and getting married, so we’re all part of it.”

Kaluuya’s professional career has evolved in fits and starts: Skins was a huge hit in the U.K., and led to a starring role on stage in the Olivier Award-nominated play Sucker Punch. In 2011, Kaluuya appeared in “Fifteen Million Merits,” the second episode of Charlie Brooker’s dystopian anthology series Black Mirror and arguably one of the best to date. But it took time for Black Mirror to become a phenomenon, and it wasn’t until four or five years later that Kaluuya really began to profit from his astonishing performance. “It’s really quite surreal,” he says. “Every British show comes and goes, and it was before Netflix was a thing. Then Netflix became a thing and I was in New York [two years ago]—I think for Interview—and I kept getting stopped. I was like, ‘I don’t understand what’s going on. This is really weird.”

Now, with Universal’s Get Out, Kaluuya has his first starring role in an American feature. Written and directed by Jordan Peele, the film is an astute satire that uses genre tropes to question the role of race in contemporary America, particularly within the context of white liberalism. Chris, a young black photographer, agrees to a weekend trip with his relatively new white girlfriend, Rose (a very chilling Allison Williams) to meet her parents in their affluent suburb. Once there, things become increasingly uncomfortable for Chris, from shameless othering at the hands of Rose’s family and friends, to bizarre interactions with the family’s all-too-chipper black household staff. While Chris grapples with his experiences—is he rapidly unravelling because of a childhood trauma that has come to the fore, or has he found himself in a Stepford Wives community?—his best friend, a TSA agent played by comedian LilRey Howery, provides perceptive comic relief via phone. The result is both laugh-out-loud and disturbing.

Though Kaluuya still lives in his home borough of Camden, he is currently in Atlanta filming Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther. He is also working on a few of his own scripts, including a feature and a television series.

EMMA BROWN: How did you get involved in Get Out? Was it the usual way—your agent sent you a script and you auditioned?

DANIEL KALUUYA: I got an email from [my agent] and read it, and I was like, “Aw, man, this is crazy. My boys would love this.” I actually called it “12 Years A Slave: The Horror Movie.” I was like, “Yo, how do I make this happen? I’m a massive fan of Jordan.” And [my agent] was like, “Oh, well, he’s a fan of you.” And I was like, “What the hell? He knows I exist?” So we Skyped a long time ago, probably about this time two years ago, and I was just saying how much I loved the script. It was a visceral reaction; I would watch the shit out of it, and all of my friends and anyone I care about would watch the shit out of it. Then it kind of fizzled out. I didn’t hear anything for a couple months. Sicario came out and I went out to L.A. after and I read for it. He literally said in the audition that I’d got the part, but I don’t really trust anyone. I waited a long time before it happened.

BROWN: When people like Jordan say that they’re a fan of your work, do they usually mention anything in particular and is often Black Mirror?

KALUUYA: Yeah. In America, what’s happened is that Black Mirror has come out on Netflix. Jordan said he watched that and he really just thought of me for the role.

BROWN: Did Black Mirror change your career in England when it came out?

KALUUYA: No, which is why I’m in America. I haven’t really had a lead role in England on-screen since that. A lead role is pretty rare for me—this is the first one since that on-screen. I’ve had a couple on-stage. So no, it didn’t really get people to go, “I’m going to cast Daniel in something.” That’s when I realized that I’m not really going to do anything that I believe in as much in England, so I started looking to America. I think I’m always going to be the risk [in England], for obvious reasons. So you go, “I’m just going to keep it moving and find my tribe.” With Jordan, I feel like I found someone that gets me. I don’t have to convince him, he just gets it. I think a lot of American people get it a bit more.

BROWN: What’s Jordan like as a director?

KALUUYA: He’s amazing, man. He’s so collaborative, he listens to all the notes, and if you’re having a problem. It was a 23-day shoot, so there wasn’t a lot of time, but he did it for us and made us feel welcome. Obviously, he has an acting background, but also he has an improv background, which I have as well and Allison [Williams] has. He allowed us to go off-script and, if it was not feeling right, just free up. Then there were some days he’d direct us as Tracy Morgan, which was incredible. He was just really fun, really welcoming, and really open and trusting.

BROWN: I really love the scene where your character gets hypnotized for the first time. You go through so many different facial expressions. What was that like to film?

KALUUYA: It was intense. But for me, it was just so well-written in terms of the dynamic and the conflict of the character—of not wanting to face something that he has to face. It’s also so interesting that he’s a black guy, because a lot of black men have problems being emotionally vulnerable because of the boundaries and parameters that have been put onto them by society. It felt really truthful that he has this backstory that’s tormented him, this shame and this guilt. He’s internalized it, and someone’s bringing it to the fore. It was so rich, there was a lot to play around in.

BROWN: I felt so bad for him at the end. He’s going to be very traumatized.

KALUUYA: He’s not going to date a white girl soon.

BROWN: I don’t think he’ll date anyone.

KALUUYA: Yeah. That’s what happens, though. That’s what happens when you open up and you go through an experience like that. It’s traumatizing. He has to seek help in order to get through it, but that’s another thing, will he seek help? A lot of people go through trauma—not exactly what’s happened in the film, but traumatic situations at that level—and they don’t, and then just have to live it and get by, which is what got him in that situation in the first place. He had the death of his mum, which is a massive loss as a kid, and he just cracked on and he internalized it.

BROWN: Obviously there are laughs in the film, but Chris is also a serious character and, like you said, he’s got a real emotional depth. Was it hard to find that when you have someone directing you as Tracy Morgan and you know that people are going to gravitate towards the comedic moments while watching the film?

KALUUYA: No, because I felt like Chris’s coping mechanism is humor. My experience growing up in London and growing up in a working class background, is that when people are down and out, that’s when they’re probably the funniest. They have to be. That’s what they do to cope, to find joy, cause they don’t feel the joy inside. Or they use humor to keep people out. I felt it was really honest because, as human beings, we don’t really make sense. I understood the serious stuff, but I didn’t want it to be transmitted as overtly. He has to be functional and open enough to even have a relationship in the first place, to be in that situation, and to have friendships and to enjoy life. And Jordan picks a time to be Tracy Morgan, so it’s all good.

BROWN: Do you remember the first time you met a significant other’s parents?

KALUUYA: My first girlfriend, we went to a play. She got a text when we were coming out of the play and she said, “Shit, my dad is here. I haven’t told him about you.” We went downstairs and he was outside in the car, and he was just like, “Come here! Come here now! What are you doing?!” It was a bit crazy. I’d never, ever met him, so it was a pretty weird situation and she was really frustrated because obviously he didn’t want his baby girl to start dating. That’s life though.

BROWN: Did you go out again?

KALUUYA: Of course! That’s my girl! I don’t care! I’ve got to do what I’ve got to do. It was all good, it was just a tricky situation.

BROWN: When we last interviewed you, you talked about a script you were writing. Are you still working on that?

KALUUYA: Yeah, I went to Sundance Screenwriters Lab. I’m still writing it. I’m going to go full steam ahead, but because of my work schedule, it’s just been a delayed situation. I went Screenwriters Lab and then I came to Alabama to shoot Get Out. That delayed the redraft process. Now I’m in Atlanta doing [Black] Panther, but I still have to deliver a script at the same time. It’s happening. I wrote a TV series back home, as well.

BROWN: Who was your mentor at the Screenwriters Lab? Did you have one?

KALUUYA: We had Thomas Bidegain, who wrote A Prophet and Deephan. He’s amazing. He’s so smart. Kasi Lemmons was one. Tyger [Williams], who wrote Menace II Society. I had loads of really cool people with really cool outlooks. It was an awakening. If anything, it was a place where I thought I knew how to write, but I had no idea. A lot of people have an opinion on scripts, but they aren’t equipped to diagnose what the problems are. You realize that scriptwriting is such a specialist subject, but because it’s so common, everyone thinks that they can talk about that. I think it’s something that writers only know, that they can see. I was doing these drafts and everyone that I was speaking to for notes weren’t writers—they were really smart people with great notes, but the problems with the script, [the people at the Screenwriters Lab] could diagnose specifically. That was what was amazing about it. Someone like Bidegain, listening to him talk about story and script is just amazing. A Prophet is one of my favorite films of all time.

BROWN: How long have you been working on this script for?

KALUUYA: I have been on working on the script since 2013, 2014. It’s been a while. It took Jordan five years to write Get Out, so I’m realizing it takes that long. It’s a process. Especially if you want to say something real about London, and what happened in London in terms of gentrification of housing and you want to be really cinematic and ambitious about it. The process takes a while. It’s cool, I’m ready for the long run. I think a lot of writing is, “What is this story trying to be? How do I get out of the way?” So it’s kind of like, “Oh, I found another bit where I’m in the way, and another bit.” But I don’t think writing stops until the film is out. In the edit, it’s another draft. [The script] is the food for set, and then the set is food for the edit, and the edit is food for the screen. It’s constant, and this is just the first stage of it.

BROWN: When you were little, were you always writing stories? Did you always know that you wanted to be a writer?

KALUUYA: I wrote my first play when I was nine. It was performed at Hampstead Theatre. I won his competition. It was really weird. The teacher thought I was an idiot. I was messing about a lot, and she’d go, “Look at Shafi”—Shafi was Bengali, she couldn’t speak English—”Even Shafi is working. What’s wrong with you?” And I was like, “Alright, listen. I can do this.” I just wrote something, it won, and it got performed. They were like, “Keep writing!” and I was like, “No. I want to play.” I wanted to play football and it didn’t really work out. At 12 you really know that this is not going to work out for you, so at 12 I was like, “I should retire from football.” Then I got into acting through improv. Improv is like writing. It’s actually a different discipline to acting. It helps acting greatly, but it’s completely different. It’s the same side of your brain when you write as when you improv. So I did that, and I started writing plays and directing them at Hampstead Theatre, youth theater. Then I got a job acting, then I got Skins. I joined Skins as a writer and actor when I was 17.

BROWN: Do you remember what that play was about when you were nine?

KALUUYA: That play was based on Kenan & Kel. I just liked their dynamic. I was obsessed by their dynamic, and it was just two guys that worked at McDonald’s or something. I can’t really remember it. I remember my whole year at school came out to watch it. It was quite an intense experience. I think it had an orange soda moment, but it was McDonald’s, so I made it Fanta or something. I would love to find it. Hopefully it’s in my room somewhere.

BROWN: I don’t know what Kel is doing now, but if you ever met Kenan, would you tell him about writing this play when you were little?

KALUUYA: I would tell him I wrote a play, but what I’m finding about being in L.A. when you meet people that you know, it’s really intense to do stuff like that. I saw the Chance the Rapper the other day. Chance the Rapper did a screening of Get Out, and I was like, “Yo, man, I went to your gig!” And I showed him my friend dancing at his gig in Camden, cause I’m from Camden. I showed him and it’s just really intense. Like, “Why are you showing me your friend dancing?” My instinct is always to keep it cool, and I went up to him, and I was like “Fuck it.” So maybe if I saw Kenan … but then I’d have to find Kel. I can’t leave Kel out. That’s not fair. They’re one. They’re a duo. Life goals.

BROWN: Has anyone in L.A. done something like that to you? “I have to show you the text I sent after I watched your episode of Black Mirror!”

KALUUYA: In L.A. I’ve had weird situations. You just don’t know how to react: “Okay. Cool. That’s a very visceral reaction you had from watching that and you’re communicating that to me. Great.” I’m just happy people give it time and that they wanted to watch it. I really believe in that episode and Charlie Brooker as a writer. So, the fact that it’s out there and people felt something, that’s what you do it for. It’s the same with Get Out. I went to a screening the other day—the Chance the Rapper one—and people were whooping and going crazy. People were present. It’s an experience; they’re not passive within it.

BROWN: People were definitely cheering in my screening, even at some of the more violent moments.

KALUUYA: Yeah, and that’s interesting as well. I did a play called Blue/Orange. It was last summer at the Young Vic [in London]. It was about mental health in the black community, but this character was quite funny. Camden had a massive amount of mental health people and people that did drugs, so I’ve been around it my whole life. It was so interesting when the audience laughed. There are bits that are really funny, but they are bits where you kind of shouldn’t have laughed. And that’s like life. So the reaction in Get Out, it means that the audience is part of the art piece. You can watch the film and that’s revealing, and then you can watch the audience as well and it says a lot about who they are and how they feel.

GET OUT IS OUT TODAY, FEBRUARY 24, 2017.