In the Middle of Somewhere with Ava DuVernay and Emayatzy Corinealdi

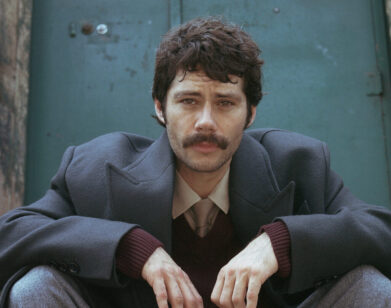

ABOVE: (LEFT TO RIGHT) EMAYATZY CORINEALDI AND AVA DUVERNAY. PHOTO COURTESY OF AFFRM.

“I think there’s an expectation of privilege—the stories that we hear of Harvey Weinstein coming in and giving Kevin Smith a three picture deal, of someone coming in, they see your little short, and you’re an overnight sensation,” writer-director Ava DuVernay explains to us when we ask her how she would advise an aspiring filmmaker. “Those days are gone… accept the reality and do it.”

We’re inclined to take DuVernay’s advice—she certainly did. Clever and determined, DuVernay successfully transitioned from film publicist to filmmaker with her own production company, the African-American Film Festival Releasing Movement (AFFRM). She’s about to release her second narrative film, Middle of Nowhere, which won her the directing award at Sundance in January, and she was recently approached by ESPN to make a documentary about Venus Williams.

You would never guess that Middle of Nowhere was shot in just 19 days, or that this is Emayatzy Corinealdi’s first starring role. As the title suggests, the film is expansive and lyrical, a prison of wide-open spaces. Corinealdi plays Ruby, a medical student trying to get to grips with the incarceration of her husband, Derek (Omari Hardwick). The audience knows little about Derek’s background or why he is in prison and is forced to rely on Ruby’s rose-colored memories of their life as a happy couple. But this is all we need to know. Middle of Nowhere is not about Derek, it is about Ruby, how she puts her life on hold for a relationship that may never resume, how her husband’s sentence infiltrates every facet of her life—from her daily routine to her career, and relationships with her mother, sister, and nephew. Rounding out the cast are the increasingly popular David Oyelowo as Ruby’s admirer, Lorraine Toussaint as her mother, and Edwina Findley as Ruby’s sister, Rosie.

We recently caught Emayatzy and her director, on what DuVernay calls the “Thelma and Louise” publicity tour, to talk about women in film, how much one should sacrifice for love, and the benefits of having Internet access on planes.

EMMA BROWN: Ava, you’ve said that you didn’t originally think that you could be a filmmaker. What changed your mind?

AVA DUVERNAY: I was a film publicist, so I represented a lot of filmmakers and I was always around them. I [started thinking] “They’re just regular people, like me, with ideas. I’ve got ideas.” That’s literally how it started. It was definitely a career change; I didn’t make my first little short until I was 32. It was kind of intimidating coming in to it so late—all these whippersnappers fresh out of film school, I couldn’t do any of that. But I did start to recognize that being so close to really great filmmakers and watching them direct on set and the experiences that I did have, although different from film school, were still super valuable. I learned just from being around. I coupled that with some very intentional study and practice—picking up a camera—and started just making it.

BROWN: Your first full-length film, This is the Life, was a documentary. What made you start with that format?

DUVERNAY: I wanted to start with this script [Middle of Nowhere]. I wrote this script first, maybe seven years ago, and couldn’t figure out how to make it. At the time I was a studio publicist, so I really didn’t know much about the indie world. Then I made some shorts and some docs and started to discover the festival circuit—”There are people making films for 100,000 dollars? Oh, my God!”—and started to find out a way to make narrative films for a certain price. But the documentaries were something that I could do for a small amount of money, and then I felt like as long as I found the truth in the stories I was telling as a doc, I could teach myself filmmaking through doc filmmaking.

BROWN: Are you ever going to make another documentary?

DUVERNAY: I’m making another one right now about Venus Williams.

BROWN: That’s so exciting. How did you pick her as the subject?

DUVERNAY: ESPN came to me after the Sundance win and said, “We love your voice, is there anything that you want to make?” So I asked them and they said yes.

BROWN: I was reading some of your interviews from Sundance, Ava, and they often emphasize the rarity of black, female, independent film directors. Are you sick of talking about this, or do you think that it is something that should be talked about and emphasized?

DUVERNAY: No, I understand it. Some black filmmakers will say, “I don’t want to be considered a black filmmaker, I’m a filmmaker.” I don’t think that. I’m a black woman filmmaker. Just like A Separation is [by] an Iranian, male filmmaker and his film is through that lens, my films are through my lens, and I think it’s valuable and fine and worthy to be seen by everyone. So I don’t have any problem with this. I like talking about all the amazing black independent filmmakers that are on the scene—there are a good number that are doing great work. And I love talking about the issues that we deal with as women filmmakers, ’cause there’s so many—the drastic drop from a woman making her second film to her third film, it drops by, like, 50 percent. Women filmmakers, after the second [film], half of them disappear. That really startled me. That’s something that we have to be mindful of as women critics and journalists and actors and directors. So, yeah, I think it’s worth talking about.

BROWN: Why do you think that is?

DUVERNAY: A lot of factors. Some suggest that, “Oh, it’s because women go and start families.” I’m like, “Really? Is that your reason?” They call it environmental factors. I just don’t think there’s a lot of support for the woman’s voice in cinema, and it becomes really difficult to raise that money and start again every time.

BROWN: I know your first film, I Will Follow, was very personal. How personal is this film?

DUVERNAY: This film isn’t as personal, in terms of, I don’t have a husband in prison. [laughs] But definitely more in terms of the scope of where I come from, the inner city, incarceration being very disproportionate in black, brown communities—[it] is really prevalent. Mother, daughters, sisters, wives—it’s certainly something I’ve observed, a secret society of all these women waiting and we never see or hear their stories. I was always kind of interested in that. At one point I thought I might just do a documentary but then I started coming up with the story of Ruby and Derek and really playing with this idea of how they’re separated and why. [It’s] not personal directly, but definitely important to me and the part of the community that I want to project.

BROWN: Emayatzy, how did you get involved in the film?

EMAYATZY CORINEALDI: Through an audition. I had initially come in auditioning for the role of Rosie, the sister. Then our casting director thought that maybe I should come in and read for Ruby. That’s how [Ava and I] met, through the auditioning process.

BROWN: But you knew Omari Hardwick, who plays your husband, before you started filming.

CORINEALDI: I did, I did. We lived in LA about the same time and we used to both frequent—and I believe he started, actually —The Actors’ Lounge, where actors get up and do monologues and all that kind of stuff, so we would see each other often through that and auditions.

BROWN: Is that sort of an open-mic night? I didn’t know that actors did that.

CORINEALDI: Yeah, every Wednesday.

DUVERNAY: I’ve never heard this story either. Open-mic monologues? That’s pretty cool.

CORINEALDI: Yeah. [laughs] Or scenes. Whatever people wanted to put up. It’s still going now. He started it with a couple friends, and I believe now the friends still run it. It’s a great workout space. You get to go and just try new things.

BROWN: Your character sacrifices so much for her husband; how much do you think that you should give up for someone that you love?

CORINEALDI: Hmm… give up as much as you’re willing to receive back and give yourself, if that makes any sense. Whatever that is, don’t expect more from a person than what you’re willing to give, but give it knowing that you’re giving it—it’s been given, so don’t expect anything else.

DUVERNAY: It was a big question I was asking in the film, but I’m not sure. What’s too much? Where do you start to lose yourself in any relationship, whether it’s mother-daughter—you start to lose yourself in light of their expectations. Then, especially in romantic relationships, especially women, we give up so much of ourselves. I’m not sure of the answer, but I hope people come out of the film exploring that for themselves.

BROWN: I ask because when Ruby tells Derek she is giving up medical school at the beginning of the film, it felt like such a mistake. And I wasn’t sure whether it’s because that’s too much to sacrifice, or whether Derek is the wrong person to make that sacrifice for.

DUVERNAY: Did you feel he was the wrong person from the very beginning?

BROWN: I didn’t at first, but the more you get to know him. Ruby is so insistent that she and Derek were happy before he was incarcerated. Do you think that she is romanticizing the past? Or do you think they were genuinely happy before?

CORINEALDI: I do. Whether that was her deciding not to see certain things… but I do believe there was one point where, absolutely, she was very happy. And I think that’s the reason for the surprise of it all: “What just happened here? We were just on the same page, where did we go wrong?” She does admit somewhere in there, “Maybe I just refused to see a couple things.” But I do think that they were genuinely happy.

BROWN: What do you think would’ve happened if he hadn’t gone to prison?

CORINEALDI: They would’ve ridden off into the sunset and lived the life that Ruby always dreamed. [laughs] Have 2.5 kids with a dog.

BROWN: Ava mentioned that you shot the entire film in 19 days; did it make it difficult to establish the right sort of bond with the other actors?

CORINEALDI: It was a hard period initially coming into it, knowing that we had 19 days to shoot and this was a feature and I’m almost in every scene. But the relationships with everyone else really came very organically, honestly. I didn’t know anyone [except Omari], but it felt like I did when we all met. When I met Lorraine Toussaint, the mom, it just felt like my mom and other moms that I’ve known before. Edwina Findley is my sister, and it felt like I know [Ruby’s] relationship with [her] sister. It just felt very familiar.

BROWN: What about David Oyelowo? He’s in so many films at the moment, how did he become involved?

DUVERNAY: Oh my gosh, do you know the story? This is the best story. I didn’t know David, but I had always loved his work and I was like, “I’d really like someone like David Oyelowo for this.” I never thought we’d get him cause he’s very hot right now and I just had this little movie.

So, David’s on a plane from LA to Toronto to do looping for Rise of the Planet of the Apes and he happens to be sitting next to, in first class, a random guy who was watching on his laptop a show called MI-5, which David was in, in London. The guy looks up at David and he looks back down, and David’s like, “Yes, that’s me.” They start talking and in the conversation that they have, it’s like a five-hour plane ride, they’re getting along great—I can imagine the people around them going, “Shut up!” And the guy says, “A friend of mine just asked me if I would invest in a movie, should I do it?” And David said, “Ah, film investment is a little shaky,” and he was like “Yeah, it’s a black independent film.” And David said, “Black independent film? Who’s the director? Is it Ava DuVernay? I just saw her on CNN,” and he said, “I don’t know, I’ll ask my friend.” So he emailed down from 35,000 feet to [our producer] Howard [Barish], “Can you send me the script?” Cause David’s like, “Give me the script!” David reads the script. I don’t know any of it’s happening. The next day, I’m on my way up to work, I get a call and it’s David with his posh British accent, “Hi, my name is David Oyelowo and you may not know who I am, but your number was at the bottom of this script.” Cut to a week later and he was in. So weird.

BROWN: You hadn’t already cast someone else?

DUVERNAY: Nope, I hadn’t even started casting it. He was the first one on board.

BROWN: Last question: What’s the strangest question you’ve been asked about the movie so far?

DUVERNAY: Earlier today, someone asked Emayatzy, “When’s the last time you had lust in your heart?” [both laugh] And her eyes just got bigger than they already are. “Lust…?” And he was like, “Yeah, you know, for shoes or cars.”

CORINEALDI: I didn’t know where to go with that: “What do you want from me?”

MIDDLE OF NOWHERE IS OUT IN LIMITED RELEASE TOMORROW, OCTOBER 12.