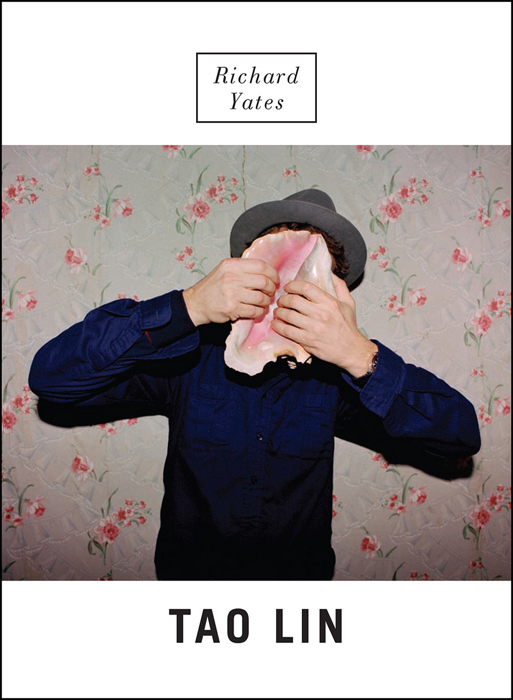

Tao Lin on Bret Easton Ellis, Indulgence

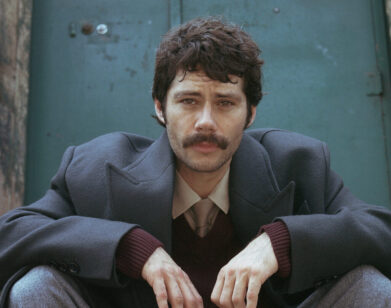

Writer Tao Lin gained notoriety last year for financing the writing of his second novel, Richard Yates, by selling shares in the project. An update: all his investors will be getting his money back, and the book, a love story between a young writer in New York and an underage girl in New Jersey, will be released on September 7 through Melville House. I recently caught up with Lin on a stoop in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, where he thoughtfully answered my questions in his signature monotone.

KELLEY HOFFMAN: Recently, The Atlantic‘s blog commented on a controversial piece you submitted to Gawker about being arrested for trespassing at NYU’s bookstore. The writer, Hua Hsu said you reveal a lot about yourself but nothing at all, “Like a marvelous joke with no punch line.” Do you agree with that statement?

TAO LIN: I agree with him that you don’t know anything about me. But I think it’s because there just really isn’t anything to know. Unless you view concrete things that happen to me as knowing things about me. I actually don’t have…opinions. I’m not being secretive about anything. I just actually don’t have opinions about society. I can discern that certain things have an effect on certain other things but I don’t view those effects as good or bad. If a context and a goal is defined I could say if it’s good or bad. But overall I don’t view things as good or bad. So I’m like a robot or computer in that sense. So maybe that’s why people don’t think they know me when they read my writing.

HOFFMAN: How did you come up with your book’s title?

LIN: I didn’t know what to title it, and for awhile it was titled Second Novel. After that I titled it Werner Herzog. And then that changed to Richard Yates. And now I view the title as a low-level non sequitur In the same manner that if I typed a really long email to someone, and finished it, and went to the subject line, and, like, didn’t know what to type for the subject, I would just intuitively pick something from inside the email, so that the other person hopefully would sense that I had titled it intuitively instead of doing it in some other way that would have defined the entire email with a tone or one clear subject. Also, if you’re, like, a PhD student in English, and you look at each instance that Richard Yates is mentioned in the book…it has sort of it’s own narrative that one could analyze and write literary criticism about.

HOFFMAN: Are you reading anything right now that you really like?

LIN: I got this book off BookMooch. It’s called Cocaine. It tells the history of cocaine and I’ve been enjoying reading that. The information is really interesting and I also like the author’s style and tone. Before that I read Bill Clegg’s Portrait of the Addict as a Young Man. I liked reading it. I like reading books where people with a lot of money use it to do whatever they want. Like stay in expensive hotels and do whatever drugs they want and fly wherever they want. Another book like that is Electroboy, which I read a few months ago.

HOFFMAN: Why do you like it when rich people do hyper-indulgent things?

LIN: Because it seems like these people have become rich and are now using all that money to do what they originally wanted to do. While other rich people might be like, “Once I’m rich I’m going to go on a vacation to wherever,” but instead they just keep wanting to be more rich. It just seems like it would be fun to do whatever you wanted. If I were really rich I would be flying places, I think.

HOFFMAN: Oh, I met Jay McInerney for a minute. I met him at the Watermill benefit I was covering. I should have asked him about you.

LIN: I’m sure he doesn’t know who I am. What did he say?

HOFFMAN: He is working on a new book. He seemed very jovial guy, like he just wants to hang out and have fun.

LIN: Oh. Interesting. I met Bret Easton Ellis at his reading at Book Court.

HOFFMAN: What was he like?

LIN: Nice. My publisher had mailed him Richard Yates. And when I talked to him he said he had read all my prose books. And he said something like, “You got a lot of mileage out of Dakota Fanning.”

HOFFMAN: Are you making this up?

LIN: No. It’s not an exact quote. He said he doesn’t give blurbs, he preempted any talking by saying that.

HOFFMAN: You’ve been compared to Bret Easton Ellis and Douglas Coupland. Like them, you make modern references, but your characters don’t seem as extreme name-dropping, hip, or ego-obsessed. What do you think of the comparison?

LIN: I think Bret Easton Ellis has said that he doesn’t completely identify with his characters. And I think he has referred to them as immoral before. But I wouldn’t think of my characters’ moralities at all. And I think I identify fully with every main character I’ve written about and would say that I am them pretty much. So in terms of that I don’t think I’m similar to him. I know he has said he has some amount of empathy for every character he has written about, though, so maybe I am similar to him in terms of that. I’m not sure what he thinks exactly. I think he has said before that his books, or some of his books, Glamorama and American Psycho maybe, are commenting on something or are reflective of a certain time period and, to me, my books are not commenting on anything, and also aren’t written to reflect a time period. So in terms of that I don’t think I’m similar to him. I’m not really sure though because I might be confusing what reviewers have said about him and what he himself has said, in terms of the things I’m talking about. I don’t know what Douglas Coupland thinks about his writing. I’ve read maybe one page of one of his books and didn’t think I was similar to him. But it seems like people just compare you to anyone, pretty much.

HOFFMAN: You do sort of feel like them, but without the fashion and the drugs and the money.

LIN: My characters definitely have less money. I like Bret Easton Ellis’ sense of humor. I feel like mine is sometimes similar to his. And how his characters sometimes seem really confused in a humorous manner. I like that. And I have that sometimes in my characters.