Pat Montandon’s Blistering Memories

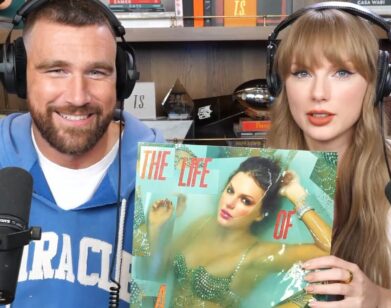

ABOVE: PAT MONTANDON

Once christened San Francisco’s “Golden Girl,” Pat Montandon was a legendary hostess to the cream of San Francisco society and celebrities, including Danielle Steel, the Gettys, and Andy Warhol—to name a few. Immortalized as a character in Armistead Maupin’s Tales of the City, she lived a seemingly perfect life in a penthouse above the Bay, complete with her multimillionaire husband Al Wilsey and their son, Sean. From her lavish parties to legendary Roundtable lunches, Montandon was always the “It girl.” Then her world crumbled: Montandon’s husband abruptly ended their marriage and married her then best friend. The ugly courtroom proceedings played out publicly for three years.

After her divorce, Montandon founded a peace group, Children as Teachers for Peace (now called Children as the Peacemakers). She then made 37 international trips with grade-school children, and has had substantive meetings with such world leaders as China’s Premier Zhao Ziyang, Chancellor Helmut Kohl, Pope John Paul II, the late Indira Gandhi, Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland of Norway, and former Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev. That concept and the resultant journeys earned her the United Nations Peace Messenger Award and three nominations for a Nobel Peace Prize. She is also the author of numerous non-fiction books, including How to be a Party Girl, The Intruders, Whispers from God: A Life Beyond Imaginings, and Oh the Hell of it All. In her new book, Peeing on Hot Coals, Montandon takes readers back to her beginnings in Texas and Oklahoma. She was a child of the Great Depression in a house full of characters and an equal amount of fine brown sand from the Black Blizzards of the Dust Bowl. This coming of age memoir is both dramatic and scorching—literally (at age seven, Montandon really did pee on hot coals, suffering severe burns that affected her entire life). Through it all, Montandon never loses her irreverent humor, vividly describing her Nazarene preacher dad, a straight-from-the-Bible-Belt mama, and her eight siblings.

We spoke with the 85-year-old Pat Montandon in her humble Beverly Hills home about her Southern-girl roots.

EMILLIO MESA: Let’s start with the title, Peeing on Hot Coals.

PAT MONTANDON: In the past, I’d told the story of going outside of our house and peeing on the coals and everyone always laughed. I then realized it would make a great book title. But it wasn’t until I started to write the story that I realized how much that experience defined my childhood.

MESA: Was it because it marked you for life?

MONTANDON: Yes, both physically and emotionally. Nature has a way of deadening us to traumatic events, until we’re ready to deal with it. And once you do, it’s a volcanic reaction.

MESA: Writing a memoir can be considered an act of resurrection. You’re essentially conjuring the scenarios of the past and every player in it. Can you tell me what that process was like for you?

MONTANDON: We were a total of eight siblings from the same parents. Now, I’m the “memory keeper,” the last living member of my family. Going back in time was wonderful and scary at the same time. I loved the characters that we all were. My mother was the tough-as-nails disciplinarian who showed very little to no emotion. My father, on the other hand, was a study in contradiction. He was the fire, hell, and brimstone preacher, while also being incredibly gentle and forward thinking. I identify with him a lot.

MESA: In which way do you identify with your father?

MONTANDON: He was the first person to invite African-Americans into his services, at a time when it scandalous and not to mention dangerous to so in the South. Because of it, he was ousted from the ministry but he didn’t care, he stood by his convictions and continued. That was the example I took from my father, when the same thing happened to me later on life.

MESA: You mean when you were the queen of San Franciscan society?

MONTANDON: [laughs] Yes. I’ve always been very outspoken and a supporter of the underdog, because I’m one as well. It all started in the early ’70s. As a feminist, I established “The Name Choice Center,” and I started using my maiden name—because if a man can’t take his wife’s name, then why should she? In San Francisco, it was as if I put a bomb in the bay. The women in the socialite circle I was in freaked out. They were afraid they were going to be strangled by their diamond necklaces, if they dared to do such a thing.

MESA: Your mother comes across as militant and emotionally conservative. Describe your relationship with her.

MONTANDON: [sighs and slips into her childhood Southern accent] She sure was, darling. I was nurtured in the fluid of grief. But how could she not be, with so many children and the loss of two? One child died halfway into the pregnancy and per doctor’s orders, she had to carry it to full term. The other was my toddler sister, who died 11 months before I was born. Looking back, I’m sure she didn’t know how to handle a new baby after those horrific experiences. But she always looked after me, especially after I burned my privates on the coals and when I wanted to “validate myself.”

MESA: Why did you decide to brand your skin with numbers, as a form of validation?

MONTANDON: [laughs] Capper’s Farmers Insurance. We had only one cherished family possession, a Steinway piano. Mother persuaded Father to have it insured. The company issued a stamp (with sharp edges) to carve the number of the policy on the piano. One day when they were out, I found the stamp, pulled up my dress, said a prayer and then sat on it. Look at me God, I said, I have a number. Of course it hurt like hell and I bled a lot—but honey, at least I was insured.

MESA: I write essays about traumatic childhood experiences, and my family always gets upset to the point of not speaking to me for several weeks. If your parents and siblings were alive today, how would they feel about your book?

MONTANDON: They would hate it. No question. They were extremely religious and never showed any weakness in public. Years ago, I gave an interview about growing up poor and mentioned we were on welfare. One of my sisters got so offended that she demanded a retraction. But I was fair and showcased all their faults with virtues—especially my own. I wrote the story as it happened.

MESA: The book is loaded with humor, as well.

MONTANDON: Thanks to my son, Sean Wilsey, I’ve learned to laugh at myself. Laughter has been my saving grace. It helps us get through the most difficult episode in life. I’ve been poor and neglected, in the middle and cherished, then rich and miserable and back to the middle and now happy. I’ve lived it all, darling.

MESA: You’ve had an on again/off again relationship with Armistead Maupin, because of the character he based on you in his Tales of the City series. But he gave a great blurb for your memoir: “Heart-tugging.”

MONTANDON: Our relationship throughout the years has been up and down, but we’re at a great place now. I’m proud of him for all he’s achieved with his writing and for giving a voice to the gay community. I do consider him a friend and can say, without reservations, that I love him.

MESA: Why did you decide to self-publish this time around?

MONTANDON: I wanted to have more control than I had with my past books, especially given the sensitive nature of the stories. But it’s been a challenge, every step of the way. You are responsible for every single aspect. Yet I have no regrets. However, it’s given me a newfound appreciation for publishers.

MESA: What do you want people to say about you after reading your memoir?

MONTANDON: I wrote the book in the spirit of total honesty and love with self-deprecation. Everyone brings their own perceptions when reading a book about a real person. At the end they will take away whatever they wish. So it doesn’t matter what I want them to take away.

PEEING ON HOT COALS WILL BE AVAILABLE SEPTEMBER 25. FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE BOOK AND ITS EVENTS, PLEASE VISIT ITS WEBSITE.