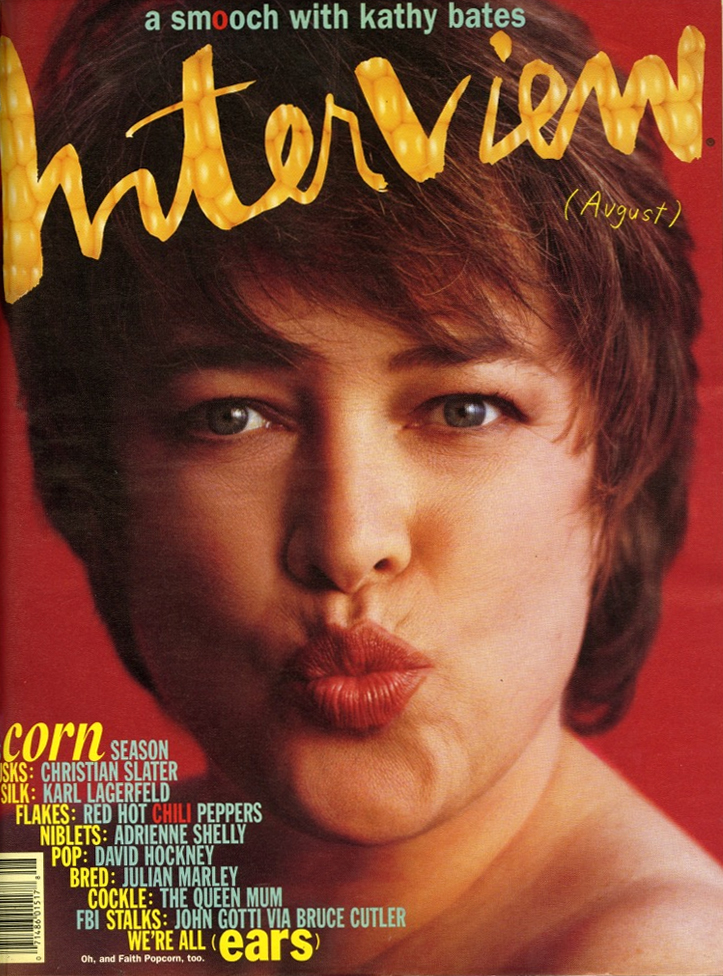

New Again: Kathy Bates

Few actors possess a range like Kathy Bates. She can play a murderous, obsessive literary fan (Misery), a stubborn, bayou-bound matriarch (The Waterboy), and just about everything in between, be it drama or comedy, film or television. With an Oscar and two Emmys to her name, at age 68, she continues to take on lauded roles. Just last week, Bates received her 14th Emmy nomination for her role in FX’s anthology series American Horror Story. If that isn’t enough, Deadline also announced that she’ll be starring in Disjointed, a new Netflix comedy series about a longtime advocate for marijuana legalization who opens her own pot dispensary.

In honor of Bates’ talent and forthcoming stoner series, we’ve reprinted Interview‘s cover story on the actress from August 1991. In it, she discusses growing up in Memphis, her life after winning an Oscar, and how now, as an “official movie star,” she has to discuss her sexual affairs with the press. —Ethan Sapienza

Kathy Bates

by Michael Lassell

Kathy Bates has kicked off her shoes. Propped up on pillows of shocking primaries—red, yellow, blue—on the plus sofa of a suite in the Mondrian Hotel on Sunset Boulevard, she is curled up in the kind of cozy position that is habitually forbidden to children. There’s something provocative about her, something regal, something primal that takes the shape of innocence. She’s uncontrived, soothing—not maternal, exactly, but clearly in touch with the earth. Her southern accent is icing on basic, unpretentious speech.

Before she became a hero—or antihero—with her Oscar-winning role as Annie Wilkes in Misery, Kathy Bates was a widely respected stage actress known for a string of revelatory performances. She played the fantasizing sister in Crimes of the Heart, was Tony-nominated for her lonely, epileptic divorcée in ‘night, Mother, and won an Obie for her over-the-hill waitress in Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune. Those roles, all originated by Bates, were taken by Diane Keaton, Sissy Spacek, and Michelle Pfeiffer in the respective screen versions; Bates managed to hold on to the overdressed loudmouth she played on Broadway in Come Back to the 5 & Dimes, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean when it was filmed by Robert Altman.

Now, with a handful of movies at various stages of completion, Bates is taking stock, trying to assimilate the plunge into fame, trying to give some intellectual and emotional shape to a paradigm shift in her life and career. On finishing Misery last summer, she spent five months in Brazil shooting Hector Babenco’s At Play in the Fields of the Lord, squeezed in a small role in Woody Allen’s Shadows & Fog, and then traveled to South Africa to star in a movie of Athol Fugard’s The Road to Mecca, returning just days before the Academy Awards. When we met in June, she had just finished filming Prelude to a Kiss in Chicago. This month she’s in Georgia making Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Café, based on Fannie Flagg’s book, after which she begins Used People, inspired by Todd Graff’s The Grandma Plays.

She was supposed to have a month or two off this summer, but the press, insatiable presses.

MICHAEL LASSELL: You still look just like Kathy Bates.

KATHY BATES: Oh, good!

LASSELL: Did anyone think Misery was going to be such an important picture for you?

BATES: The men’s-wardrobe supervisor did… my sister, my brother-in-law. But I thought that was just family talk. I knew it was a tremendous movie for me, because how many pictures are there where a character woman gets to play the lead? I was looking at Gena Rowlands on TV this morning. I am always knocked out by her work because of the strength of it. It’s that combination of strength and femininity at the same time that I’ve always admired. I’ve never liked the namby-pamby, [tiny little voice] wimpy-wimpy-wimpy…

LASSELL: It’s an incredibly difficult balance, isn’t it, femininity and power?

BATES: The thing that I’ve run up against is that it’s always been an either-or proposition, especially in Hollywood. You’re either young and glamorous and you’re going to get the lead and get the man at the end of the picture, or it’s the opposite: you’re a character actress, you’re not attractive enough for the other role, and so you’re playing the friend or the killer or the lesbian or the doctor or whatever. But the one who gets to play the young, pretty, gets-the-boy-at-the-end role doesn’t have any power. And vice versa: a character can have power, but not femininity.

LASSELL: Misery was written and directed by men, but it’s an equal battle between one man and one woman. And she doesn’t really lose, does she?

BATES: I don’t think she does, because I think she makes Paul [Sheldon, played by James Caan] fight to the very last ounce for what he wants and what he believes. On one level, it was like he met the devil. I prefer to think of it in terms of my response to the novel: he was reborn. In the book, Paul Sheldon begins unconscious. And Stephen King refers to Annie Wilkes as this African goddess. He has two words on the frontispiece, “Africa” and “goddess,” and there are all these references to bees and the queen bee. To my mind, he was getting into something very primitive—Mother Earth, Rebirth, Nature.

These are things I think about. Maybe this is going off of the deep end, but as we readdress ourselves to Mother Earth in this day and age—which is the only problem confronting us, because if we don’t fix it then nothing else matters—and as women begin to take more power in society, and as men and women begin to balance the masculine and the feminine in themselves, I do think we are “Reinventing Eve,” to steal from the titles of Kim Chernin’s books. And I think that’s very exciting.

LASSELL: You seem to be a perfect example of someone who has struck a workable balance.

BATES: Mmmm…

LASSELL: I’m not trying to put you on the spot, but you’re a very feminine and very attractive woman, whatever Hollywood may say about your casting category. Does it make you uncomfortable to talk about yourself?

BATES: It’s strange. There’s a sense of giving away things that make up part of yourself. I’ve always tried to be honest, and it would be too difficult for me to develop some kind of persona. I don’t have enough time or energy for that. But there is a sense of depletion. It’s like somebody just moved into your head and took out all the furniture, you know? So I can sit here on the couch and hear you say, “You’re very feminine and very attractive,” but I have always struggled with that. I find it safer to pursue the powerful, the ugly, the unpleasant. As my mother would say [thickening her accent], “You always play these people with af-FLIC-tions.” Maybe it’s because I know that I can’t possibly win at the other.

LASSELL: You didn’t have a happy childhood, did you, down there in Memphis, Tennessee?

BATES: No, it was awful. I didn’t go out on one date in high school. I played guitar and sang and wrote my own music and poetry and stuff when I was a teenager.

LASSELL: What was your reaction when you heard Michelle Pfeiffer was cast in Frankie and Johnny?

BATES: I laughed hysterically.

LASSELL: Come on, the truth.

BATES: I did! I swear to God. I was in Brazil, and it was six o’clock in the morning. I went down to breakfast and handed the fax around the table to my pals and said, “You’ve got to read this!”

LASSELL: Michelle Pfeiffer is a good actress—

BATES: She’s a great actress!

LASSELL: —but she’s too gorgeous to play Frankie.

BATES: If you’re talking in terms of the play, it’s not good casting, but I haven’t read the screenplay. When I first went to interview for Misery, they were saying things like, “You’re not Michelle Pfeiffer, you know.” And I just don’t get the relevance of that remark. I’m not Elizabeth Taylor, either. I’m not Sean Connery. I don’t understand why it’s so importation to compare people to Michael Jackson or to Madonna, or whoever—people assume you have already processed and understand.

LASSELL: You may find, as you wind your way through the maze, that there’s a lot of that predigesting going on in Hollywood. It wouldn’t surprise me if your agent [Susan Smith] got a lot of psycho-women scripts.

BATES: She didn’t, actually. Of course, that may have been because of that article in the L.A. Times quoting her as saying nobody in Hollywood has any imagination. On Monday morning people were calling her, saying, “Here, we have imagination. Read this.”

LASSELL: It seems that the obvious benefit from Misery is that now you get to be the star.

BATES: [laughs] Well, I don’t know about that!

LASSELL: You don’t think it’s a benefit, or you don’t think it’s going to happen?

BATES: Because I’m a woman, because I’m a character actress, because I’m over 40, I’ll be very interested to see, not just for me but for other actresses, how Hollywood treats us in the next ten, fifteen years. I’m hoping that it’s not going to be so easy to shove people under the rug, as they have in the past. There are a lot of powerful women in Hollywood who have been movie stars for a long time who are getting into their forties and fifties. I still want to see them work.

LASSELL: You mean you would go to another Meryl Streep movie?

BATES: [laughs] Wouldn’t you?

LASSELL: I would do anything Meryl Streep ever asked.

BATES: See, there’s someone I’ve always admired, because she, more than anyone of our sex, is able to do what Laurence Olivier did, and transform herself into all kinds of characters, with accents and makeup and hair and everything, which is why we all wanted to be actors in the first place—to play! That’s the word we all forget. It’s so difficult to do that in film, because they want you to be yourself. That just gets to be so boring and so limited. There’s nothing creative about that.

LASSELL: You’re downright indignant.

BATES: I am! I just don’t get it. Ugh! It’s like in the circus, which is what we’re all in, let’s face it. You’d think that the more unusual, the more way-out, the more bizarre a stretch you make—[barker’s voice] “See the amazing transformation!”—that that’s what everyone would go for. And they go for just the opposite! Look at Linda Hunt. There’s somebody groundbreaking. She played a man in The Year of Living Dangerously. That’s the kind of stuff I want to do. I want to find my Popeye Doyle [from The French Connection].

LASSELL: You could have played Popeye Doyle!

BATES: I wouldn’t want to take it away from Mr. [Gene] Hackman. The problem I have these days is that women are often cast in a role—as a police officer, for example—and then are invariably perceived by the other characters as succeeding in a man’s job, as if they’re doing it in spite of being women. I want to see women onscreen the way I see them in society. O.K., we had women’s lib in the ’60s, the women fought for their roles, they’re out there in the work force. Now let’s talk about how they’re dealing with things as human beings.

LASSELL: You’ve been working nonstop lately.

BATES: I had a week off between Misery and At Play in the Fields of the Lord.

LASSELL: In which you play the sexually repressed wife of Aidan Quinn.

BATES: Mmm-hmmm.

LASSELL: How do you play a sexually repressed woman who is married to Aidan Quinn?

BATES: [laughs] He’s very attractive and a wonderful actor. We all had a great time in Brazil. We all said to each other after the first couple of weeks, “Thank God we all like each other, or it would have been awful.”

LASSELL: You seem to be much more sanguine about these glam queens snatching your stage roles now that you have an Oscar.

BATES: I know. But I find that I’m fighting to keep my energy and my passion centered on the work and not on “Will this get me an Oscar?”—which is the way people are starting to talk to me. I’m not interested in the way people are starting to talk to me. I’m not interested in looking at a role that way. That’s not what I ever did, and it’s not how I can continue to do my work. I still have to have a visceral response to the material and to the role. The relationship to the director is becoming more crucial to me, making sure there are some common goals. I haven’t been in the kind of position where my roles have been chosen for me, where someone says, “First we’ll do this and then we’ll do this,” and it’s all part of some master plan. It’s been a slower, more spiritual journey for me.

LASSELL: So no one has yet said to you, “And then you’ll do a comedy with Mel Gibson”?

BATES: [laughs] I don’t think you should print that, because I think it’s a great idea! And we don’t want to scoop it ’til we get it out there to the studios. I think we should put this in development!

LASSELL: You certainly seem a lot less depressed now than when you were doing ‘night, Mother.

BATES: I think with ‘night, Mother I danced too close to the flame. I became inflamed. It was such a scary, life threatening experience for me that I never wanted to go back, because the journey there was long and arduous. Along with all these other things that I’ve been thinking about lately has been this sense—and I think part of it has to do with my work with Aidan, because he’s such a committed actor and so fresh and spontaneous—that I have to go back to the flame, that I have to immerse myself more in the work. I think I’ve danced away a bit too far.

LASSELL: What was working with Woody Allen like?

BATES: He was certainly very nice. And, Jesus, you know, such a legend. I didn’t feel particularly excited about the actual process. I don’t know what kind of a development process making a film is for him, but to my mind, working on a set with people like Lily Tomlin and Jodie Foster and John Cusack, and all these great people in my little scene…

LASSELL: All those people were in one scene?

BATES: Yeah.

LASSELL: What was the scene?

BATES: I don’t know.

LASSELL: It’s a secret?

BATES: No. I don’t know.

LASSELL: You just have no idea how it fits into the picture?

BATES: No idea about anything. I never saw the script.

LASSELL: Well, was it shot in a butcher shop?

BATES: It was set in a brothel, turn of the century.

LASSELL: And you are all playing prostitutes?

BATES: Three of us were playing prostitutes. Mia [Farrow] was in it. I don’t know exactly what role she was playing.

LASSELL: But you wouldn’t turn down a larger role in a Woody Allen movie, would you?

BATES: I don’t know. I jumped at the chance to be in one, but in this particular case it was very unsatisfying to me.

LASSELL: It wasn’t a collaborative experience, eh?

BATES: That’s the word I’ve been looking for! I adore Woody. I don’t want to hurt his feelings.

LASSELL: So I assume you did not have an affair with Woody Allen.

BATES: [roars with laughter] I spent a week in a corset with Woody Allen.

LASSELL: The two of you in one corset?

BATES: [still laughing] One corset.

LASSELL: And you didn’t sleep with Jimmy Caan, either?

BATES: [still laughing] In his dreams!

LASSELL: So who have you had affairs with?

BATES: My dog!

LASSELL: O.K., don’t tell us about every single affair, just the ones with famous people.

BATES: Listen, Madonna and what’s-her-name already did that, didn’t they?

LASSELL: This is the difference between being a respected American stage actress and being a movie star.

BATES: I have to talk about who I slept with?

LASSELL: Exactly.

BATES: Really?

LASSELL: Uh-huh.

BATES: Forget it!

LASSELL: Didn’t you introduce me to your fiancée once? And now you’re not going to get married?

BATES: [smiles] We are.

LASSELL: This has been going on a long time.

BATES: Almost thirteen years.

LASSELL: But now that you’re famous, don’t people hit on you all the time?

BATES: What do you mean? To go to bed with them?

LASSELL: Usually there’s a dinner first.

BATES: Hit on me for what?

LASSELL: I meant it in the trashiest possible sense.

BATES: That’s so funny! You mean all the time I was walking my dog and people were stopping their cars, it was for that?

LASSELL: What kind of dog?

BATES: Yorkshire terrier, the one I’ve always had.

LASSELL: Another question I wanted to ask you—

BATES: Are you serious? Hit on me, like sexually—is that what you meant?

LASSELL: I did mean it. Yeah.

BATES: Nooo!

LASSELL: Really?

BATES: Maybe I’m not having the right career. [mock whine] They’re not doing any of the stuff they’re supposed to doooo!

LASSELL: Are you going to direct films someday?

BATES: No.

LASSELL: You really just want to be an actor, don’t you?

BATES: Right now I don’t know what’s going to happen someday. I am trying to get this acting part down first. Then I’ll decide what I want to do.

LASSELL: Well, Miss Bates, after your less-than-idyllic childhood, I’m glad your adult life is redeeming itself.

BATES: You and me both, honey.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE AUGUST 1991 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.