James Wolcott’s Old New York

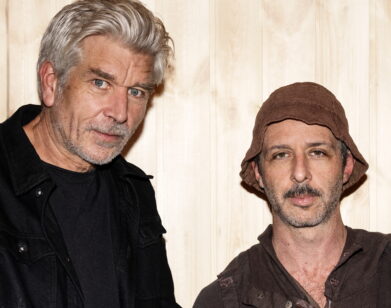

JAMES WOLCOTT. PHOTO COURTESY OF PATRICK MCMULLAN.

Writing used to be dangerous. In James Wolcott’s memoir Lucking Out: My Life Getting Down and Semi-Dirty In Seventies New York (Doubleday), Wolcott describes the rough city where his career began and the dynamic newspaper editors, cultural critics and icons who ran its gritty streets. From Norman Mailer and Pauline Kael to Patti Smith and the early punks, Wolcott’s book is peppered with anecdotes and insider insight into the movements and movies that would come to shape modern Manhattan. Wolcott brilliantly evokes the dark screening rooms where he first witnessed films like Blue Velvet, the beer-stained clubs of St. Mark’s Place, and the low-rent real estate that captivated and hosted so many ambitious artists. An author of several books and longtime culture critic and blogger for Vanity Fair, Wolcott reviews his past with a humorous and thoughtful eye. We spoke with Wolcott about going from Baltimore bookworm to downtown notable, the films that fueled his dreams, street smarts, the lascivious old school of publishing, and how his ambition ultimately paid off.

ROYAL YOUNG: What drove you to New York, and what kept you going when words and ambition didn’t feed you?

JAMES WOLCOTT: What first got me here, in the most practical sense, was Norman Mailer’s offer to write a letter of recommendation for me to The Village Voice. I thought, “This is never going to happen again, he may move on, he may forget.” I knew right away I had to make the move. Once I got here, part of it was there really was no Plan B. So it was just hang in there, and part of the virtue of being oblivious is I just didn’t know any better.

YOUNG: That instinct to grab the Mailer opportunity and then to stick it out, where did that drive come from in you?

WOLCOTT: I have no idea, the same way I have no idea why I was such a fiend about reading when I was younger. It didn’t come up in my family or in school. I was a freak. If kids cut school, they either went to The Block, a notorious section of Baltimore with lots of really crummy strip clubs, or they would go to Ocean City and get bombed. I would go to the library, or a great newsstand that had every out-of-town, counter-culture paper.

YOUNG: So the newspapers and avant-garde reading were in wild contrast to your context.

WOLCOTT: Yes, I remember reading about police arresting this filmmaker making this freaky movie and his name was John Waters. And I was like, wow, someone in Baltimore is doing something creative? I didn’t know there were people running off and making eight-millimeter movies. Then I got to New York and realized, oh, there’s a whole world of people who do these things. I was utterly bored being in the suburbs, but I didn’t know why I was bored.

YOUNG: What was your biggest misconception about the life you would find in New York?

WOLCOTT: I thought it was going to be more, like, adult cocktail parties, where people said really witty things. That definitely came out of movies. I should have known better. I think I had this strange idea it was going to be like Breakfast At Tiffany’s, or there was this movie that Gore Vidal and I both loved called Youngblood Hawke about a Thomas Wolfe-type novelist who comes to New York with all this primal energy and brittle repartée. Or I thought it might be like All About Eve, but instead it was just people yelling at each other.

YOUNG: How did a sense of danger shape the New York you knew, and how did it affect the artists and aspiring people around you?

WOLCOTT: There were a lot of apartment break-ins. There was one film critic I know who not only had many break-ins, but they, like, tied him to a chair while they ransacked the apartment. And there was a lot more peeping through windows. Your internal geography was different, there were certain areas that I just would never go to. An early piece I did for The Village Voice was about an improv comedy club, that I think was on 46th Street west of Times Square, and that was a very scary walk when you would leave that club after 12:30 at night. In every Neil Simon play and every sitcom, there were jokes about getting mugged. It was just taken for granted. It made you more guarded, but it also gave me a street sense that I’ve never lost.

YOUNG: I grew up in the Lower East Side and even as kids, we’d say, “If you go to Avenue A, you’re adventurous, B, you’re brave, C, you’re courageous, and Avenue D, you’re dead.”

WOLCOTT: [laughs] I never heard that. That part of the East Side, there was once an editor I went over to see and there were literally mounds of garbage burning in the middle of the street.

YOUNG: Do you think ambition is a substitute for love?

WOLCOTT: I think it’s a desire for recognition. People want to be special. I think ambition can take in a whole package of things, power or sexual excitement.

YOUNG: Why do we now rarely have writers and reviewers that are larger-than-life celebrities in their own right?

WOLCOTT: The whole ecosystem of celebrity has broken down for writers. If you go back to the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s, writers were on TV a lot, and they were allowed to misbehave a lot. Truman Capote was a pop figure, but it wasn’t until he went on David Susskind’s show and had that extraordinary voice and manner that everyone could imitate, that he really took off as a figure. Norman Mailer and Vidal, the same thing. The bestselling writers now, there’s no great animal energy with them.

YOUNG: Let’s shake it up.

WOLCOTT: Yes, people want somebody to be a daredevil, even if they’re not going to be a daredevil themselves.

YOUNG: Have the Internet and blogging made writing a more solitary art?

WOLCOTT: Somewhat more solitary and more splintered. It removes the whole sense of the magazine as an organism. A certain dynamism. At The Village Voice, there were all these fevers inside the offices, that would break out into full-scale rumbles between writers. The New Yorker used to be notorious for everything that went on, sexual intrigues and people had individual offices, they could close the door and take a bottle out of their bottom drawer or have sex on their desk.

YOUNG: Was being down and out, struggling, succeeding, and everything in between ultimately worth it?

WOLCOTT: Oh sure. I can’t imagine anything else at this point. I don’t really remember the depressing parts. I’m sure they were there, but I’ve sort of blocked them out. It was a blast seeing shows at CBGB’s, seeing Television at 1:30 in the morning doing their second set. Going to a New Year’s Eve show on 14th Street with John Cale and Patti Smith, that was a great kick.

JAMES WOLCOTT’S LUCKING OUT: MY LIFE GETTING DOWN AND SEMI-DIRTY IN SEVENTIES NEW YORK IS OUT TODAY.