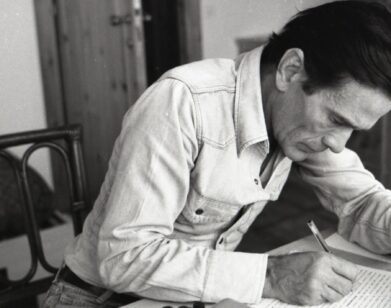

Hamilton Morris, Prophet of Pharmacology

PHOTOS BY KARLEY SCIORTINO

Hamilton Morris is a young writer, chemist and filmmaker. He is a wizard of pharmacology, a psychedelic explorer, a maestro of all things mind-altering. You may know Hamilton from his column in Vice, Hamilton’s Pharmacopia, where he writes about rare drugs and their effects to a fanatical degree. He is also the man behind the VBS documentary series of the same name. In his most recent doc, NZAMBI, Hamilton travels to Port-au-Prince to investigate the strange phenomenon of the Haitian zombie; the film follows his quest to procure the secret formula for the potion used in Vodou zombification rituals. But this is merely one of Hamilton’s many curious and magical adventures, as he shared with us recently when we paid him a visit at home.

KARLEY SCIORTINO: What’s your most prized possession?

HAMILTON MORRIS: I once owned a stick coated with Phyllomedusa bicolor skin secretions given to me by a Mayoruna Indian chief, but it was thrown away by a dyslexic Craigslist prostitute who I used to live with. He thought it was a piece of trash. I also have a diagram of the DiPT molecule drawn and signed by Alexander Shulgin, and on one occasion I traded a small quantity of crystalline psychotridine for a lion’s eardrum.

SCIORTINO: If you had to name a favorite drug…

MORRIS: That is an impossible question, as there are different materials for different occasions. I have a deep affection for DiPT, a psychedelic, and pramiracetam, a nootropic. And several others, which I probably should not mention—I’m being a bit vanilla, so forgive me.

SCIORTINO: Your house is a bit disorderly, you do not have sheets on your bed, there is some mold growing in your bathroom, and you claim not to shower often. Is personal hygiene something that is important to you?

MORRIS: Cleaning is the ultimate Sisyphean task; you sweep the motes of dust into the air, where they fall back down to the ground. It makes me feel like a cartoon character to sweep, like I am a Sim-person sweeping Sim-dust. The same goes for sheets and pillowcases. One must ask oneself the question, who is protecting who from what? Am I protecting my face from the pillow or the pillow from my face, and regardless of the answer, how is a pillowcase the solution? What protects the pillowcase? Why not put a pillowcase-case over the pillowcase, why not sleep in a Russian doll of recursive protective linens, why not put on successive pairs of underwear until I turn into the Mandelbrot set? This is mise en abyme; it is a recipe for madness that can be eliminated with the understanding that the pillow is already encased. The mattress is already covered, and the dust is seemingly governed by Aristotelian spontaneous generation and no amount of sweeping will ever eliminate it.

SCIORTINO: If you could offer one lesson to the recreational-drug-taking population, what would it be?

MORRIS: Simply because you take drugs does not mean you are an expert on them. In fact, there seems to be an inverse relationship between drug consumption and drug knowledge: more of the former results in less of the latter. If that seems obvious, you have probably gone easy on the former, though this relationship only applies to curious people who are seriously interested in drugs. But it can never hurt to do some basic research: start with Google Scholar and work from there. I say this not out of snide condescension, but out of love—love for you, and most importantly love of knowledge and the pursuit of truth.

SCIORTINO: Of the drugs you have tried, which have you found most erotic?

MORRIS: There was a designer sildenafil analogue, I believe it was sulfoaildenafil, marketed under the brand name Stiff Nights, which resulted in a few days of sub-clinical priapism—not exactly sure if that was erotic.

SCIORTINO: You own a lot of books by David Foster Wallace. What is it that you love about him?

MORRIS: I love DFW with a burning passion. He is one of very few writers that approach something close to the way humans think. That is to say, his writing is psychedelic in the etymological sense—it is mind-manifesting. His low latent inhibition, his maximalist style, it’s exciting in a way few things are—literary or otherwise. As a result there will be a backlash against him, DFW will become uncool, because the postmodern paradigm must be burned for new growth to spring from its stylistic ashes, but replacing literary postmodernism is, of course, a hopelessly postmodern task and maybe it’s best not to discuss this. Maybe we should all become slam poets.

SCIORTINO: You spend a lot of time in the library. I find libraries to be rather sexually stimulating. Would you agree?

MORRIS: There was a Russian cult of eunuchs known as the Skoptsy who were renowned for their proficiency as mathematicians, bankers, and moneylenders. Outsiders called them rapacious but this was simply their jealousy speaking—when one is freed from sexual desire, or sexual desire is transmuted into work, suddenly the world becomes engorged with possibilities. I envy the asceticism of the Skoptsy and wish I could attain a similar level of removal from the carnal temptations of the moment, but those gonadal androgenic hormones are crucial for hippocampal neurogenesis, so I can’t justify auto-castration just yet. Although, I have gone to library every day for the last three years, most nights sleeping on the floor using my shoe as a pillow, so that’s a start.

SCIORTINO: What are some of the questions you are regularly asked, or topics that are regularly raised by your admirers via fan-mail Facebook messages and e-mails?

MORRIS: One person recently asked me, and I quote, “It’s possible pulverizer marijuana for later snort?” I always answer to the best of my abilities. I have had people who deal in psychoactive chemicals ask to pay me as a consultant, to keep them up to date with various trends in the designer drugs and pipeline pharmaceuticals—but that kind of gray-market business is not for me.

SCIORTINO: Do you hope to be remembered, and for what?

MORRIS: On one hand I have great literary and artistic aspirations, but being remembered for anything is an accomplishment, even if it is ingesting the world’s largest quantity of semen or being struck by lightning the greatest number of times.

SCIORTINO: And lastly, does taking drugs automatically make a person cool?

MORRIS: No. Doing drugs is like anything else—predicated on taste, refinement, dignity, distinction, and originality. Cocaine is not cool, because it makes people act cartoonishly fiendish, and that is undignified. But when you get into more obscure territory, matters of cool become unclear. Is intraocular temazepam injection “cool?” Well, it’s unusual and by virtue of its unusualness, interesting, and by virtue of its interestingness, cool—if one were to follow that chain of propositions.

Self-destruction is only as cool as it is novel. There is nothing cool about consuming ten-dollar drinks at whatever incredibly loud bar with the vague hope that you will be photographed and vanity-stroked on a blog the next day, but if I throw hydrochloric acid on my face and blame it on an imaginary black woman in a Starbucks parking lot, that may be cool.