Francesca Segalâ??s Modern Families

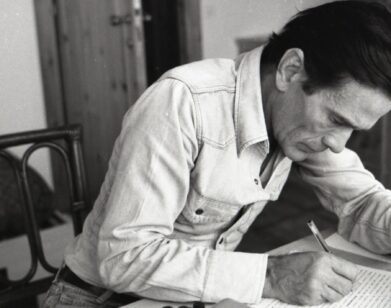

FRANCESCA SEGAL. PHOTO COURTESY OF LAURA HART.

A blended family is always ripe subject matter for high drama, and in Francesca Segal’s riveting and hilarious second novel, The Awkward Age (Riverhead Books), multiple conflicts ensue when James, a middle-aged, divorced, American doctor, and Julia, his widowed, English, piano-teacher girlfriend, decide to live together in North London. When raging hormones also get the best of their teenage kids, the parents’ carefully constructed second act threatens to be blown apart. Throw in colorful extended family members, the tension of exam season with a place at Oxford up for grabs, and former flames who seem to stay in the picture, and Segal has crafted a page-turner with great prose, humor, and a lot of soul.

Francesca Segal was born in 1980 in North West London, where she still lives. Her debut novel, The Innocents, won the 2012 Costa First Novel award and the Betty Trask Award. She is the daughter of American author, Erich Segal, who was best known for his 1970 novel Love Story and the movie of the same name.

JEFF VASISHTA: In this novel the teenage kids’ relationship in a blended family threatens to ruin that of their parents. Was this based on first-hand observations?

FRANCESCA SEGAL: The noble ambitions and unavoidable challenges of creating blended families seemed deserving of attention. I read an article about step-families in which one had this exact dynamic: parents in love, then the kids—rather sweetly, if cataclysmically—fell for one another, and I was struck by the fact that they all sounded like kind, good people, stuck in a godawful situation. Fundamentally everyone loved everyone else, but they were busily making one another’s lives as difficult as possible. At 15 it takes almost unheard-of generosity of spirit to think, “My mother has been alone a long time, she deserves love and happiness.” Instead you just think, “What the hell is wrong with my mother, thinking she is entitled to behave like an actual person?”

VASISHTA: There are some wonderful descriptions in this book. Pamela, James’s ex-wife, a sort of O.T.T. Earth Mother type, is hilarious—all silk, flesh, and hair. Where did you dream her up from and how did you envision James, who seems generally so civil and calming, falling for her?

SEGAL: James is from a working-class Boston neighborhood and after he battled his way to Harvard, I think Pamela just overwhelmed him. She has sexual and intellectual self-confidence, she’s very clever, wherever one might stand on her hippy philosophies, and James was very young and thrust among a privileged elite to whom he’d never before been exposed. She wanted him, and he succumbed. And, let’s face it, she has a great rack.

VASISHTA: Iris, the mother of Julia’s deceased husband, is also fascinating. The reader can’t help but feel conflicted about her. On the one hand, she’s so funny and steals every scene she’s in, and on the other, she treated her former husband, Philip, so badly that when he too falls in love late in life, we can’t help but cheer for him.

SEGAL: I’m so thrilled to hear you say that because it’s what I wanted—Iris’s complexity is what I loved about writing her. She’s generous one moment, stinging the next. I adore her.

VASISHTA: Your dad was also an author and often the kids of successful people end up doing well in the same profession. In your case was it osmosis or were you driven to emulate him?

SEGAL: Probably both. I adored my father and when I was a child, I wanted to do anything he did, but mostly I think his passion for language permeated and informed my childhood. He was a Classics professor by day, and so etymology and literature were the twin religions of our household. He took such joy in words, and that in particular was infectious. The only permissible reason to leave the dinner table, growing up, was to get the dictionary.

VASISHTA: Your first novel, The Innocents, won the Costa First Novel award and also the National Jewish Book Award for fiction. You touch on anti-Semitism in this novel when Nathan’s friends are getting drunk in the park. It’s a casual remark, which Gwen rightly finds offensive but she doesn’t speak up. Being Indian and British I remember being in similar situations. Now Brexit and the rise of the right throughout Europe seem to have sent us hurtling back in time. It makes the anti-Semitism furor surrounding the Labor Party all the more shocking. Are you conflicted in any way about the upcoming election?

SEGAL: There’s also Julia’s mother lurking in the background, who’s not so wild about the Jews either, and could have done with a far less exotic son-in-law. I am anxious about every election in Europe now. I think your phrase “hurtling back in time” is absolutely spot on, and very frightening. I am half-American, half-British, and the one-two Trump-Brexit punch has been winding. From whence came this impulse to kick shut the door behind us? I come from a Holocaust-ravaged family—I can testify to the consequences of turning away refugees.

VASISHTA: This book is very funny but it also touches on some deep issues, abortion being one. Without giving too much away, were there a lot of drafts and different outcomes you played with before settling on the one you did?

SEGAL: I thought a lot about it. I very much believe that a writer must honor the truth of a narrative and that if it slips from the destination you initially intended, you must follow. But I was also aware that touching on these issues brings with it a political responsibility, and I wanted to be careful that I didn’t unwittingly create a narrative that could be used to endorse an anti-choice message. These are dangerous days for women’s reproductive rights. Still. I remember being in an airport when my editor called, halfway through this precise discussion. I was pacing up and down at the gate, but as the phone call went on I felt I was drawing more than the usual irate glances—closer to rage, or maybe horror. It was only afterwards I realized what I must have looked like. Heavily pregnant—with twins, and therefore comically enormous—happy as a clam, lumbering back and forth and bellowing into my phone, “Well there’s absolutely no question, it must be an abortion. Great! Totally agree—abortion it is, I’ll get to it this weekend,” et cetera. I’m amazed no one phoned the police.

VASISHTA: What’s an average day for you? Do you have a writing schedule or go in fits and starts?

SEGAL: I have come to accept that the procrastination for which I had previously bullied and chastised myself is an essential part of my working process. I find myself leaving my desk for the nth time in a morning with an urgent need to reorganize a shelf, or defrost the freezer, or suddenly realizing that I can’t go another minute without reading the first chapter of a novel I’ve not clapped eyes on for 10 years. I used to sink into a mire of self-loathing after these episodes thinking, “Everyone in offices is off being so professional and productive, why can’t you focus?” but I’ve slowly come to see that my creative mind works in fits and starts, as you say, and I’ll have 20 minutes of furious typing followed by an hour of necessary restorative nonsense. I’m a sprinter, I think, not a marathon runner. Or maybe that beefy man at the gym who does a single heavy set and then struts around for half an hour in his Gold’s Gym vest, looking self-satisfied. I’m exactly like him, without the self-satisfaction or biceps.

VASISHTA: What was your awkward age and why?

SEGAL: Being extremely square at a post-Fabian progressive school in my teens made me feel a desperate misfit—everyone else was smoking weed and rampantly snogging one another, and I was busy with my extra-curricular Latin. When you’re 16, the boys go wild for extra-curricular Latin, I assure you. Then I moved to a school at which it was cool to do well and I adored it, but was overwhelmed by the opposite anxiety—suddenly everyone seemed dazzling and more ambitious than I was, and I had to pedal very hard to keep up.

I also found my late twenties pretty challenging. By then it seemed everyone else I knew was established in careers, barreling towards and past goals, and I was a freelance journalist, scrapping for 50 words here and there, longing more than anything to be a novelist. Then it didn’t seem the path less traveled by, rather pie-in-the-sky fantasy. Everyone’s writing a novel, after all, but most of the people who tell you they’re writing a novel also have a full time job with a pension and paid sick leave. I was intimidated by absolutely everyone.

Then the painstaking reclamation of one’s mental real estate and bodily autonomy after having a baby is pretty bloody awkward. People speak of the infant learning the me and the not-me, but that is a lesson for the mother, also, and not always very elegantly learned. Just when I think I’ve graduated from an awkward age another one comes along. Isn’t the truth that there are multiple awkward ages? Maybe better to count the fleeting periods of stability and calm between them, when life is so consuming one forgets to feel awkward and just lives. For a novelist, professionally analytical and introspective, those are few and far between, and to be cherished.

THE AWKWARD AGE IS OUT TOMORROW, MAY 16, 2017.