Expat Lit: Abdellah Taïa

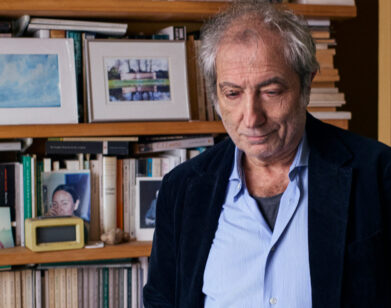

Possibly the only openly gay author from his native Morocco, the young Abdellah Taïa has chosen a vocation of literary transgressor and cultural paragon. Beginning with his second novel, Le Rouge du Tarbouche [The Red Tarboosh] published by French press Editions Séguier in 2005, the soft-spoken son of a civil servant began openly challenging Moroccan state laws aimed at silencing gay culture. A cover-story in the influential French-Arab journal Tel Quel followed, with the caption reading: “Homosexuel, envers et contre tous” [Homosexual, against all odds]. During the resulting public furor, and, amid calls for the author’s indictment for heresy, Taïa composed the very personal L’armee du Salut [Salvation Army], a bildungsroman of his youthful dreams and indiscretions set in Rabat, Tangier, and Geneva. Along the way he introduces and confronts the figures that most affected his formative love-life: an elusive mother, an omnipotent brother, and a Swiss lover. (PHOTO: ABDELLAH TAÏA, COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR)

Now published in English by academic samizdat Semiotext(e), Salvation Army is a valuable contribution not only to queer fiction but to North African diaspora literature as well. A resident of Paris over the last decade, Taïa has joined the column of Moroccan expatriates–Tahar Ben Jelloun and Abdelkebir Khatibi, among others–who cast a telescopic eye over the thorny and often violent ideological interchange between postmodern Europe and postcolonial Africa. But Taïa’s words are not scrawled with the bellicose politics of a partisan; rather, they are auguries of a familial world imbued with both magic and poverty; lilting and resolute; a prose of stark divinity and apostasy.

We recently contacted Taïa during his reading tour of the US and asked him to share his thoughts on the state of literature, the sexual politics of the Arab world, and the role of cinema in his writing.

ERIK MORSE: The first chapter of L’armee du Salut painted such a vivid landscape of your childhood, particularly how you first became aware of sex almost through a kind of familial osmosis. Can you describe a bit more about this house which plays such a fundamental role in the book?

ABDELLAH TAÏA: Hay Salam is the name of the neighborhood where I grew up. It is located in a city called Salé, near the Moroccan capital Rabat. Salé is known in the Moroccan imagination for its 17th and 18th century pirates who used to attack the Christian ships sailing through the Atlantic. I lived there from 1974 until 1998. Everything I have known about the world comes from this city and this neighborhood. Everything I want to put in my book is also coming from this world. The house where I lived there was very small, only three rooms for eleven people. One room for my father, the second for my older brother, Abdelkebir, who exerted a big influence on me, and the last one for the rest of the family: my mother, my six sisters, my little brother and me. Life for me still revolves around these three rooms. The tastes, the smells, the images, the ideas of fear and transgression are all coming from this house, this poor family that I love and hate at the same time. For many years, we were really poor, we didn’t have enough food and we fought with each other a lot. The power structures within the family were a mirror of the dictatorship Morocco was living under at that time.

My house in Hay Salam is the place where I learned about this displacement of things, being in the place that society wants. One of my sisters was possessed by a djinn [a spirit] and, thanks to her, I know today the meaning of the invisible world. I know what is it to speak with other forces, to hear other voices, and to go through that without feeling ridiculous. With this sister I had my first experiences of creativity. With my mother, a strong woman, the relation was difficult and strange: she only loved her older son. Surrounded by all these people I learned also about how sexuality is coded and expressed through mixed and elusive signals. The promiscuity of bodies in this house was difficult to endure because I couldn’t have a personal space, but at the same time it was an opportunity to witness directly the complexity of how human bodies interact. Among my parents, sisters and brothers the boundaries were not clearly defined. I suffered from loneliness inside of this hive. I couldn’t find a place for myself.

MORSE: The description of your first sexual encounter in the movie theatre in Tangier combined with the various references you’ve made to directors like Douglas Sirk and Fassbinder very much underscores the affinity you have for movies. Can you tell me what initially lured you to cinema?

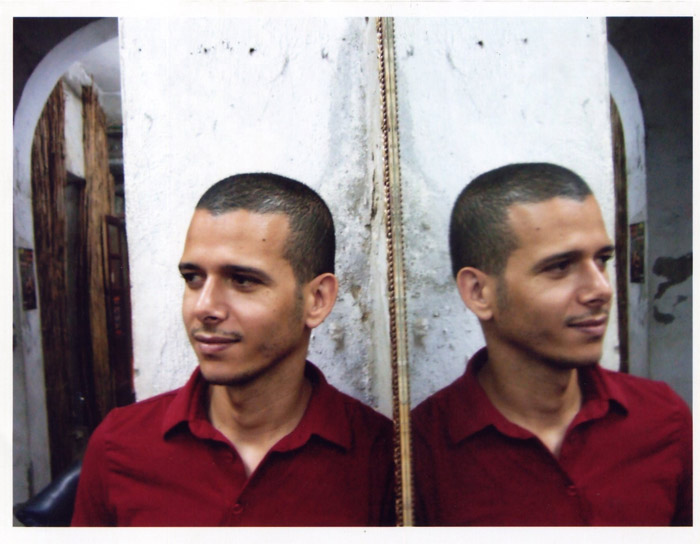

TAÏA: I first encountered movies on Moroccan television when I was a child. Egyptian films are very popular in the Arab world. I still love them a lot. When I discovered that I was homosexual and that there was no possibility to change, I understood that I had to hide this really impotent part of myself. Cinema helped me to deal with affliction and this killing of myself I was experiencing. When I was thirteen, cinema represented a space where I could be exist as Abdellah–teenager, homosexual–in silence.

The movie theaters I used to go to only showed popular films, melodramas from India and martial arts movies from Hong Kong. Although they’re not considered masterpieces, these films were, for me, the essence of cinema. They entered though my body not though my intellect. These films are still in my heart and they influence for sure my way of writing and being in life. To be faithful to them is like being faithful to my family and is something I found in myself as I started writing a text or a novel. I don’t think I am under the influence of movie directors like David Lean, Douglas Sirk, Fassbinder, or other great filmmakers. The cheap cinema is not cheap for me.

Later at seventeen, I fell in love with the French movie star Isabelle Adjani. She’s French but from an Algerian father and German mother. She is very beautiful in a strange and sublime way. When I first saw her images in movie magazines I told myself, she’s possessed like my sister. I can relate to that possession. Isabelle Adjani brought me the dream of Paris. I am not comfortable when I say I am a writer, my books seem to me like movies. They are filled with images and dreams coming from cinema and Isabelle Adjani.

MORSE: The image or trope of Morocco (and particularly Tangier) in literature as a world of escape and debauchery has figured very prominently in a type of European colonial novel and particularly “transgressive” literature from Genet to Burroughs to Gysin. As a gay Moroccan writer, how does one speak about this same world without being “seduced” by the over-sexualized image of the Moroccan male so prevalent in this type of literature? Do you find the work of those authors to represent a kind of sexual colonizing of what it means to be Moroccan?

TAÏA: I don’t think I speak about the same Morocco. Until the age of 22, I had never met any Westerner visiting my country. Like a lot of Moroccans, I come from a really poor background. We are amongst ourselves. Now I know about Jean Genet, William Burroughs, Brian Gysin, Edith Wharton, Paul Bowles, and other writers who came here and wrote about Morocco. But knowing their writing isn’t influencing what I want to say about Morocco. Their books weren’t available when I grew up. What I want to write about is this world I have inside of me where the characters are not under the power of Westerners. It’s an important point for me–to resist and to be transgressive is not an idea that was imported from outside Morocco.

There is today a controversy around Paul Bowles in Morocco. Some say that he used Morocco and Moroccan boys and exploited them. A lot of Moroccan intellectuals are trying to minimize his major contribution to Moroccan literature and Moroccan popular culture. I don’t agree with these people. He understood so many things about my country that held no interest for the intellectuals of Morocco. They didn’t pay attention to popular things, and a lot of it would have been lost if not for him. I think my generation is tired of hearing all the time that our problems are due to colonization. We don’t define ourselves anymore through this theme.

MORSE: At the same time that you are very vocally petitioning for public acceptance and government protection for homosexuality throughout the Arab and Muslim world, there is a kind of opposing movement within Europe and American queer studies that is calling for the depoliticizing of gay culture. In other words, some queer activists would prefer the ideology of gayness be replaced by a kind of undifferentiated sexuality of play and obscurity. Do you think this is a valid form of political protest?

TAÏA: I’m not sure I understand the theories developed inside the very protected walls of queer studies departments in American universities. I don’t have a theoretical background. I write from my own sensibilities and knowledge. I write novels and poems, not essays. But I don’t write only to say that I am homosexual. A novel is a complex entity. In the Arab world they try to keep us far from ourselves. They convince us that we should not define or interrogate things. That was the rule until now, and it had a disastrous affect on us and on our culture. Not to stand up to say who we are is playing the same game that those in power play on us. It is also a sort of betrayal to those who can’t express themselves….Poor Arabs don’t have that opportunity. Even today I consider myself as a poor Arab. The thankful and moving letters and emails I get everyday from people inside and outside Morocco testify to a despair and hope from people who are still feeling the burden of their own oppression. They thank me for having the courage to take a stand for them, to talk about things that we are not supposed to talk about.

Semiotext(e) will host a release party for Salvation Army Bluestockings Books at 7 PM tonight. Bluestockings is located at 172 Allen Street in New York.