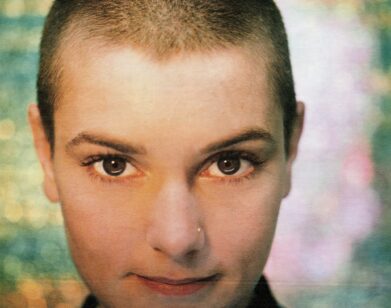

Yoko Ono

Little Boy: The Arts of Japan’s Exploding Subculture” is the third installment in the “Superflat” trilogy curated by Japan’s current art superstar Takashi Murakami. Hosted by New York City’s Japan Society and running through July 24, the show explores Japan’s obsessive otaku (geek) subculture and its extreme fixation with things horrific (radioactive monsters, atomic apocalypse), huggable (Hello Kitty), or somewhere in between (lolicom “Lolita complex” figurines). In addition to a number of works by contemporary Jap-an-ese artists like Yoshitomo Nara and Chinatsu Ban, the show features an exhaustive array of pop-culture artifacts-toys, manga, anime, and films that address Japan’s postwar cultural state of mind. On the eve of the exhibition’s opening, Murakami sat down with legendary artist, activist, and rebel Yoko Ono at the Interview offices, where the two got to know each other over lunch.

Takashi Murakami: It’s nice to see you for the first time.

Yoko Ono: Same here.

TM: I actually have a lot of questions for you.

YO: Well, then, please go ahead!

TM: We’re familiar with your works all over the world. Sometimes you do concerts with young musicians in Japan, with peace as your message. I see that your events always lead to big movements. I always wonder how you do that.

YO: You know, honestly speaking, I think my life has always been unplanned. So when something comes along, I feel like, Why not give it a try? It’s fun to experiment like that.

TM: So, would you say that there is some spontaneity in your work?

YO: Quite a lot, I’d say.

TM: When I see your work I feel like it’s been well organized based on some kind of framework.

YO: Maybe there’s some “framework” that I am not aware of. [laughs] What about you? How did you come to start your creative work?

TM: I started differently from everybody. Every-body else seems to have started with talent, but I didn’t have any talent, which is what led me to do what I do now. I didn’t start my career by doing what I really wanted to do.

YO: What do you mean?

TM: I actually wanted to become a manga artist.

YO: Why couldn’t you become a manga artist?

TM: I probably didn’t have enough talent for that.

YO: But you draw so well.

TM: Well, over the last few years, I’ve gotten quite a crash course in manga-style drawing. [both laugh]

YO: So are you saying you were doing not manga but more traditional art?

TM: Yes. When I was young, I visited New York once-

YO: What do you mean by “young”? How old were you then? Come on, you are still young! [both laugh]

TM: I was 27 or 28. And on that trip I was so stimulated by the city. I wanted to come back and base myself here, which was basically my motivation to become an artist.

YO: So you have been active here from the beginning of your career?

TM: I guess you can say the basis of my career as an artist started here. You also established your basis as an artist here in New York, right?

YO: Yes. It was in New York that my works started catching attention.

TM: Including that famous piece with a magnifying glass? [“Ceiling Painting (YES Painting),” 1966]

YO: Yes, including that one.

TM: I am a foreigner from Japan and don’t speak English well, and yet I am living here in New York as an artist who must express himself.

YO: You say you don’t speak English well, but you’ve started making your way. That’s impressive, you know.

TM: I still have a long way to go with English.

YO: But you have been successful. How did you start getting known? Through painting?

TM: Yes. Galleries in the West have probably been looking for exoticism. That’s the reason my paintings initially sold well, I think. And then once they started selling, people said my works were very detailed. They may have represented something Japanese to them.

YO: But you were able to sell your works from the beginning, which is impressive. Tot-ally the opposite of my case! [laughs] You said you wanted to become a manga artist, but you can still do anything you want from now on. Es-pecially now that your name is known.

What surprises me now is even though discrimination against women and racial discrimination still exist, they have improved a lot, especially among artists. And just when I felt I could finally take a break, I encounter this age discrimination.Yoko Ono

TM: What do you think of that? Do you also feel like you can do anything at this point, Yoko?

YO: Yeah, I feel that to an extent. I think we are both in that situation. The more I think about it, it’s incredible that you’ve become successful here without being able to understand English at all. Exoticism can only get you so far. I also think you’ve got guts to present your work. You didn’t doubt your work and kept on going, which deserves quite a lot of credit.

TM: You think? If anything, I think I was being naïve. [laughs]

YO: No. I think deep down you had a very strong desire to do this.

TM: I don’t think I’m being rude, but I felt something very nostalgic for some reason seeing you like this today. Hearing your voice and watching your movement is lifting up my spirits.

YO: I’m happy to hear that.

TM: Wherever I go as a Japanese artist, I find your footprints and encounter your precedent as an artist. So maybe I feel more familiar with you in that sense. Just now you said I had guts; I don’t know if it’s that long ago to say “back then,” but I think you are the one who really needed guts back then.

YO: Oh, I definitely needed guts! But what surprises me now is-even though discrimination against women and racial discrimination still exist, they have improved a lot, especially among artists. And just when I felt I could fi-n-ally take a break, I encounter this age discrimination. I turned 72 and started noticing a drastic difference in people’s attitudes. I started with racism and sexism in the beginning and fought them so hard and was finally ready to relax. Then, here comes ageism, and I feel like, “Give me a break!” [laughs]

TM: Your life has been a real survival story.

YO: Oh, yeah.

TM: I was so shocked to hear that you go to Sean [Lennon]’s concerts and get too excited to fall asleep. It’s unbelievable how much power you have.

YO: [laughs] Yes. I think if you give in and accept society’s stereotypes, then you start thinking, I cannot dance till late at night be-cause I’m 70.

TM: You have been dancing a long time, right?

YO: Yes, I love dancing. Oh, also something hysterical: I live on 72nd Street, and from 72nd down to Washington Square there are more than 70 blocks to go downtown and cross-town, but I can walk down there without any problem.

TM: Oh, wow!

YO: I did that three days straight with my friend, and then he got exhausted and begged me to skip the next day. And he is only in his thirties; I was so shocked. If you don’t exercise at all and your body gets tired and you take a lot of drugs or sleeping pills to sleep well-I don’t think you could walk 70 blocks.

TM: So you are not taking any drugs now?

YO: Only vitamin pills.

TM: I actually like taking medicine.

YO: You do? Well, I did lots of drugs in the past. I mean, the bad ones. [laughs] So I cannot do it anymore.

TM: I haven’t done any of those intense ones.

YO: That’s good for you. I envy you for that. Back then we weren’t aware that those drugs were bad for your health. When artists would read that, for example, Jean Cocteau was taking drugs, we would think, Wow, maybe we should do that. And everybody was doing it.

TM: So you could see another world?

YO: Yes.

TM: I think I would be rather scared to see that world.

YO: But you don’t necessarily have to do drugs to see that world, you know. My book, Grapefruit, is one example. I wrote it when I was totally drug-free, but everybody says, “She wrote this on drugs, for sure.”

TM: So you were able to see another world without drugs. [laughs]

YO: Yes, I guess you can say that.

TM: You mentioned racism, ageism. Do you think the bias against you is a factor that encourages you to express yourself?

YO: Yes. I am the type of person who would do something thoroughly if someone said, “I don’t think you can do it.” [both laugh] I am ex-tremely rebellious. I have this strong, defiant spirit. So when somebody raises ageism, I cannot help responding with an attitude like, “I’m gonna fight through it!”

[Food arrives. Ono and Murakami begin eating.]

YO: [After a bit of silence] I think they would be disappointed if they found out that we just quietly ate the whole time and didn’t talk at all. And all that was recorded was the sound of eating. [both laugh]

TM: Well, the other day I saw Hayao Miyazaki’s latest film in Japan [Howl’s Moving Castle]. It was about this girl who is put under a spell and transformed from a 19-year-old to a 90-year-old lady. What happens is that when she can put her thoughts together, she goes back to being a young woman.

YO: Interesting.

TM: But when her thoughts are scattered, she switches back to being an old lady.

YO: It sounds like a fantastic film. Very deep. I think it’s true that our thoughts determine our age. You know, when I’m clear I still feel really young. I look at myself in the mirror and I know sometimes I am young and sometimes I am old, but to tell you the truth, I always wonder, Am I really in my seventies? [laughs]