Fragments of Gordon Harrison Hull’s Interior

At only 37 years old, Gordon Harrison Hull is an established name within the fashion, art, and advertising industries. While a junior at NYU, studying “post-modern millennium theories of creativity,” he founded the boutique and creative studio Surface to Air, and although he parted ways with the company in 2011, he now acts as the Creative Director for a large American fashion label and continues to pursue his own freelance projects. Hull is also an artist in his own right, with works currently on view in his first-ever solo gallery show, “Department of the Interior,” at Bryce Wolkowitz in Chelsea.

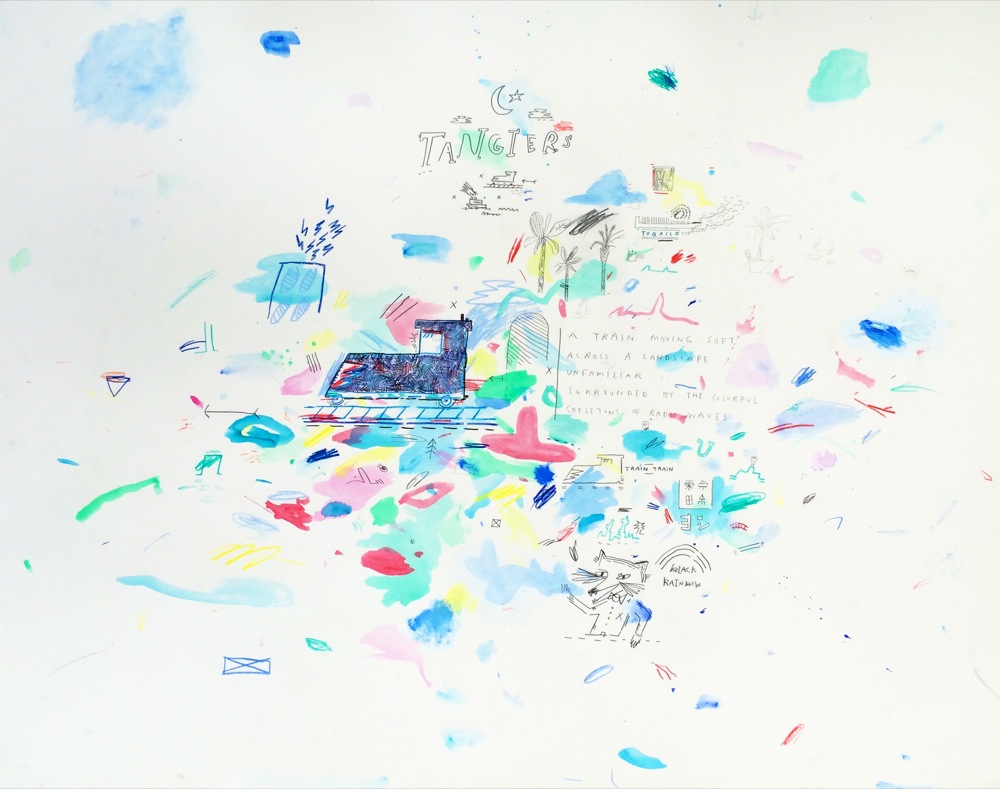

Drawing inspiration and information from his college major, childhood, adult life, and former collaborations, Hull’s pastel abstract drawings and paintings provide glimpses into fragmented stories culled straight from his imagination. Words and short poems provide hints of plotlines; recurring symbols reflect his exposure to Africa and the country’s art through his father, who was a professor of African history; former partnerships with brands like Suno, Tory Burch, Adidas, and Marc Jacobs lend a hand to his concise, yet impactful storytelling. Like the name of the exhibition, each work acts like one department of Hull’s own interior, depicting various places, objects, and people that hold special significance.

“My work has gone from a crazier place to a more minimal place, and I have plotted the journey; I’ve been watching it happen,” Hull says. The canvases of earlier works in the exhibit are covered from corner to corner, while the recent works place an emphasis on concise contemplation with excess negative space.

We met with the artist at Bryce Wolkowitz the day of the show’s installation. It was the first time he had seen any of the works framed, and he was as thrilled a kid in a candy store.

EMILY MCDERMOTT: Congratulations on your first solo gallery show.

GORDON HARRISON HULL: I woke up and I was like, “Wow, okay, this is happening! This is really happening!” A lot of this work is about decision and restraint, because I can’t fuck up. I can’t erase anything—everything is watercolor, pencil, and ink. Anytime I make mistakes I need to keep on going to make the mistake work again. For me to get to this point and be like, “I don’t want to touch this anymore, I love this,” it’s really so difficult.

MCDERMOTT: The negative space has increased in your recent works. To you, what does the negative space mean?

HULL: I’ve never really thought about the negative space, but it’s like little breathing points. All of these things are like weird clips of dreams: you have a daydream, or just a half an hour dream, or a nightlong dream.

MCDERMOTT: It’s also interesting that you write the titles directly on the works.

HULL: That happens because there’s always stories. It’s essentially these little narratives, little films, I have going on in my head. They’re all characters. For example, [in The Secret Passage] you’ve got this woman, you’ve got Kathmandu, you’ve got this idea of secret passages, you’ve got a weird sort of cat figure. They’re just stories…

This [work] is The Picasso Dance Move—so much of my work is about rhythm and dance. The act of making these lines, there’s a rhythm to it. Then I’m always thinking about dance—there’s always an element of that, so this is the story of “the Picasso dance move.” I like the idea that Picasso, as a dancer, would have a signature move, and [this is] how would I express that.

MCDERMOTT: Are the stories all fictional or are some based on your experiences?

HULL: A lot of them are made up, but I’ve done tons of traveling. My dad was a professor of African history, so I grew up obsessed with Africa, surrounded by Africans who were always coming to visit. But aside from the fact that my dad’s background is in African history and my parents’ house is covered in African art, I grew up on an apple orchard in upstate New York—the classic America, apple pie, white picket fence. So I had this weird mix of “all-American Africana” and I think that’s always informed everything I’ve done.

Through my dad, as a child, I also traveled a lot through Africa. I traveled all over the world, and that has always been a part of my work. There’s always locations. A location to me is an idea about something: it’s a look, it’s a feel, it’s a color palette, it’s a storyline. I was also in Paris for forever [with Surface to Air] and I speak French, so there’s a lot of French in some of the work. It’s blending worlds, cultures, colors, dreams, ideas, and marks, and the marks are all about the sense of energy, ideas, and existence. I’m making my mark and it’s about proof of life, in a way.

MCDERMOTT: I want to go back to growing up with a dad who’s a professor of African history. I read about the rather unique way you were born. Can you talk about that?

HULL: My parents had me when they were older, like in their early 40s. My mom and dad tried to have kids for a decade, so the doctors had said, “Look, I don’t think it’s going to happen. You should look into an adoption.” My dad was like, “I’m going to Ghana for a couple months and I’m going to have a witchdoctor make a fertility dress for you, from the Ashanti people in Kumasi.” So he went to Ghana, had this fertility dress made, brought it back, my mom wore it, and she had me. She wore it again eight months later, got pregnant with my brother, and had my brother. Then she put the dress away. [laughs] Never brought it out again. I saw it for the first time maybe 10 years ago. I don’t know what the truth in it actually is, coincidence or mind over matter, whatever it might be; it’s just an amazing story.

MCDERMOTT: Do you consider yourself a spiritual person?

HULL: I’m totally spiritual. I’m not remotely religious, but I definitely believe in some shit out there. I was baptized as a Methodist, but first they had me baptized in an African ceremony—me, in a thing of hay, with a white picket fence around me, and then an African guy in this amazing outfit, and some drummers…I grew up with my dad always saying magic is real, spirits are real.

When I was 18 we went to Kumasi, where the dress was made. About six months before, I had this series of dreams about these mountains; there were fires, and I could hear these noises, and I woke up in a room surrounded by books. It was a crazy dream, but I had it a couple of nights in a row. So we go to Kumasi, and when we get there, my dad’s like, “We’re going to be staying at this school in the mountains that I helped build in 1963.” The school had a room for my dad, but they were like, “The only place we can have you sleep is in the library.” That night they put me in this tiny little gazebo surrounded by books, and I wake up in the middle of the night—I hear something, I see the room full of books, and walk outside and look out on all the mountains and there’s fires everywhere. Then in the distance I can hear people drumming and singing. It was incredible.

On top of that I became obsessed with other instances of natural magic like magnets, lightning, electricity, and things like that. I was like, “All of these things are unexplainable. How does a magnet work? What is electricity?” A lot of those things really informed my work—the disembodiment of the story and the narrative. So many of these symbols are African shapes.

MCDERMOTT: They remind me of early African art and very simple wall drawings.

HULL: They’re really gleaming stuff from African sculpture. They come to me from this sense of the way simplicity and metaphor work in African culture and art. In African art, drawing an elephant is very simple, but it’s never really about an elephant; the elephant tells a story. It means something a lot larger.

MCDERMOTT: But you still have many Western influences too, like Elvis in Return to Sender…

HULL: So here is the story: Burkina Faso is a country in Africa, the Mossi are a very old tribe in Burkina Faso, [and] I am obsessed with Elvis. I had this weird idea about an Elvis-y sort of guy—maybe not Elvis, but a pompadour guy with sunglasses, smoking a cigarette—hanging out in Burkina Faso. It’s combining these weird, disparate elements, like Elvis in Africa; Elvis never really went to Africa. I am like, “It would be amazing if Elvis gave a concert in the middle of the plains surrounded by these crazy huts.” “Return to Sender” is one of my favorite Elvis songs. Again, these are straight up me drawing my own versions of African masks and stuff.

MCDERMOTT: How did you come to such a calm, pastel color scheme?

HULL: A lot of it has to do with the dreaminess. I love watercolors because they flow and are very soft and pastel, and the colors are always that way. Those, to me, are the foggy moments, the foggy color of the memory of a dream.

MCDERMOTT: Do you have a studio?

HULL: I work at home. I just do it on the floor. My house looks very similar to a gallery. It’s cement floors, this giant wall, and I’ll have two or three drawings at once. With Surface to Air, we were traveling all over the world to do projects. I had two studios—one in New York and one in Paris—and I found I was never in either. My work started to get smaller and smaller. The only time I had to make work was when I was traveling. So I used to make really big canvases, and they got smaller and smaller and smaller, until everything was happening on medium size pieces because I could travel with them. I had to be nimble; I had to be able to throw it down, do it, pick it up, and put it away. That really changed everything.

Also, the writing got kind of funny because we were always focusing on consultation projects for advertising agencies. An ad agency would be like, “We are trying to pitch Hugo Boss, and obviously we know nothing about fashion. If you come up with a campaign we are going to pitch it and pay you a pile of money.” I started to learn about copywriting and coming up with tag lines and titles for campaigns. All of a sudden I noticed how words were also getting smaller and smaller. They needed to get more and more impactful. It’s like pre-Twitter.

MCDERMOTT: And now your poems are like Tweets or haikus.

HULL: They are. I was using Twitter a year ago as a place to put poetry; I think all my poems are now 140 characters or less. That came from copywriting. That is basically the world we live in, where the shortest poems need to be a lot more impactful. There has to be something said by each that elicits a number of feelings or a vibe.

MCDERMOTT: What is one of the biggest struggles you’ve faced that has really informed who you are and your work?

HULL: Space and time. I don’t have the luxury of working on anything for a very long time because I am always on the move. I’m constantly battling, “How far am I going to take this? When is it done?” Because I can’t erase, it’s always a real risk to build these compositions, and compositionally these are so fucking complicated. They drive me crazy. My wife is like, “For work that’s really happy and really fun, you get so angry at it.”

MCDERMOTT: So what do you do to decompress?

HULL: I make other work.

“DEPARTMENTS OF THE INTERIOR” IS ON VIEW AT BRYCE WOLKOWITZ GALLERY IN CHELSEA THROUGH JULY 31. FOR MORE ON GORDON HARRISON HULL, VISIT HIS WEBSITE.