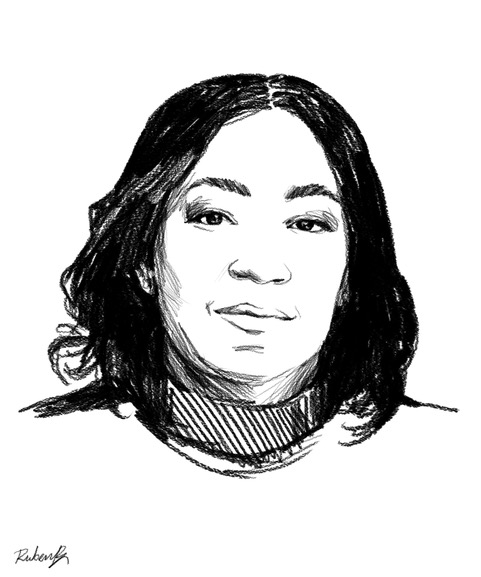

Ask a Sane Person: Brit Bennett on the Interconnectedness of Protests and the Pandemic

Brit Bennett has written the novel of the summer—if not the year—with The Vanishing Half, her dazzling American tale about race, family, and sisterhood. Born and raised in Southern California, Bennett may be one of the most exciting fiction writers of our interconnected cultural moment. She’s an astute observer of the times, all the big horrors and small triumphs, and to read her is to understand how the past keeps such an enduring grip on the present.

———

INTERVIEW: Where are you and how long have you been isolating?

BRIT BENNETT: I’m in Los Angeles right now. I was isolating in Brooklyn by myself from March to July, and finally flew out to spend the summer with family.

INTERVIEW: What has this pandemic confirmed or reinforced about your view of society?

BENNETT: We’re all interconnected. It sounds cheesy, but that’s the terror and hope of this whole crisis. On one hand, it’s horrifying to see these chains of infection emerging from places of intimacy and closeness—weddings, funerals, birthday parties. It’s horrifying to imagine that I could harm someone I love just by wanting to be near them. But on the other hand, I’ve never seen a clearer example of the responsibility we all have to take care of each other. I hope that when the pandemic ends, we’ll continue to feel that responsibility.

INTERVIEW: What has this pandemic altered about your view of society?

BENNETT: That we are not as entrenched in tradition and conventional belief as we claim to be. We all constantly hear self-described pragmatists argue that certain things are impossible or inevitable or unwilling to change. Then, in a matter of weeks, we saw the whole world shut down. Nothing is impossible to change.

INTERVIEW: What is the worst-case scenario for the future?

BENNETT: Our planet becomes unlivable due to climate change, and along the path to extinction, generations of poor people struggle to meet their basic needs as the wealthy continue to horde all available resources.

INTERVIEW: What good can come out of this lockdown? Are there any reasons to hope?

BENNETT: Back in March, I was encouraged by all the people donating to food kitchens and mutual aid funds. It seemed, for a moment at least, that people were recognizing our interconnectedness and realizing that we have a responsibility to our communities. Then later, during the protests, you saw people donating in mass to bail funds, and I’m not sure that you would have seen that if not for the experience of donating during the pandemic. It felt like in this moment, it became abundantly clear that we all have a responsibility to directly help and support and protect those in our communities—that idea gives me some hope.

INTERVIEW: What has been your daily routine?

BENNETT: Lockdown, for me, was split between life before my new book came out and life after. In the before, I was writing in the mornings, watching lots of TV at night, and checking in with friends and family to maintain my sanity in my apartment alone. After the book, that turned into less writing and lots of Zoom events for the book.

INTERVIEW: Describe the current state of your hair?

BENNETT: Ugh. Let’s also not talk about the current state of my eyebrows.

INTERVIEW: On a scale of 1 to 10, what is your level of panic about the current state of the world?

BENNETT: It’s a sliding scale? I’m not as panicked right now as I was, say, in March, because I’ve experienced this crisis long enough to begin to feel a bit more stable. I’ve learned to accept some of the unpredictability and to realize that I can only control so much in such a volatile time. I’ve also been fortunate from the very beginning to be able to work from home and to know that my family was also able to be safe at home. That being said, we’re in the middle of a global pandemic with a president who stopped trying to solve this crisis because he got bored of it. Oh, and in a few months, we’re facing the possibility of him being our president for four more years. So, like, an 8? But it’s more of a quiet panic, always humming along beneath the surface.

INTERVIEW: Do you think there is hope for true racial equality in the United States? What do you think is the first step in that goal?

BENNETT: I don’t know. My gut reaction is no. Racism is so integral to the narrative of America that it’s hard to imagine this country otherwise. But at the same time, I don’t like to say no because I think about all of the Black folks who’ve come before me and who strove to improve this country for future generations. If they didn’t give up hope, who am I to?

As for the first steps, I don’t even know where to begin. Maybe unlearning the myth of our own national innocence. I don’t know how you can strive toward equality without first seeing yourself clearly as a nation. We need to divorce ourselves from the childish idea that we can end racism by simply being nicer to each other or by rebranding symbols to shed their offensive history. We need to think about how racism actually operates in this country, and how we’re implicated within these systems of power. You can’t undo a system until you’re able to honestly face how you first benefit from it.

INTERVIEW: How can America work to ensure more equality and justice on a day-to-day level?

BENNETT: Dismantle our carceral system, invest in education, expand and protect access to voting rights.

INTERVIEW: Do you think protests are effective tools for changing the system? How does it make a difference in the long term?

BENNETT: I mean, the protests have already led to change, or, if not tangible change, then they have widened our imagination toward what change is possible. The protests have led to Black Lives Matter becoming so mainstream a phrase that the NFL, of all organizations, has adopted it. We’ve seen some truly embarrassing gestures toward solidarity, but we’ve also seen policy shifts that we hadn’t seen during previous protests, like police officers being fired swiftly for misconduct or cities cutting police budgets.

As for whether these changes will last long-term, who knows? The protests have always, to me, seemed deeply interwoven with the pandemic. For one, we’re experiencing a global pandemic that is disproportionately killing Black and brown people. A month in, our leaders began rushing the country to reopen because they did not care that more Black and brown people would die. Then, in the midst of this horror, we watched a white officer casually choke the life out of a Black man. So casually, his hands were in his pockets as he killed him. There was something particularly sinister about witnessing this when we’re all sheltering in place, presumably in order to save lives. The lockdowns were such an act of communal sacrifice and solidarity, where everyone suffers for the greater good, and then while everyone is lonely and anxious and worried about lost jobs, sacrificing for the sake of preserving life, we saw a white cop casually snuff out the life of a pleading Black man.

How many times have horrifying videos like that gone viral? I think the context of the pandemic made the video even more horrific. And beyond that, we are in this surreal moment, witnessing society transform in ways we’d never imagined. Whoever thought they’d see New York City shut down for months and months? Whoever thought that we would spend months trapped in our homes, unable to see friends and family? If that’s possible, then why can’t we defund police departments? Why can’t we rip down Confederate monuments? Nothing is inevitable anymore. I don’t know whether the protests will leave lasting effects. Will we be forever changed by living through this pandemic? Or in a few years, will we largely go back to how life was? I don’t know, but it certainly feels like something has shifted.

INTERVIEW: How do you personally channel your anger? Do you find anger to be a useful emotion?

BENNETT: I think anger can be useful in life, but I don’t find it useful in my writing. Not to knock it for other writers, I just don’t think I’m interesting when writing from a place of rage. Perhaps because anger is most useful when it’s pointed and precise, and my writing feels most interesting to me when it meanders.

INTERVIEW: Who are the young leaders of the moment that you are inspired by?

BENNETT: Everyone who took to the streets, in the middle of a global pandemic, facing a violent state counter-protest, and risked their bodies and their lives.

INTERVIEW: What’s the next step after protests in the streets? Where does the righteous rage go?

BENNETT: I hope it doesn’t go anywhere. I hope we continue to hold our leaders accountable. I loved all those clips of people cussing out government officials on Zoom. I think rage is a healthier part of democracy than indifference.

INTERVIEW: Do you work best alone or in a group? Can you protest from home?

BENNETT: Definitely alone. I think there have been lots of ways that people have protested from home, like the K-Pop stans who thwarted Dallas PD’s snitch app. Why can’t that be considered a form of protest?

INTERVIEW: Americans tend to find the topic of race uncomfortable. How do we start the conversation and address it directly?

BENNETT: I think by Americans, you mean white Americans. I’ve been talking to other Black people about race my entire life, I don’t find it uncomfortable at all. Nor do I find it uncomfortable to talk with my other friends of color. I think white people need to examine why they find the topic of race so uncomfortable. Okay, here’s an example: in college once, I went to see some friends sing at a gospel choir concert. A white family sat behind me, and the 5-year-old daughter immediately asked the dad, “Why is everyone in here Black?” Loudly. And the dad, naturally, freaked out and said, “Don’t say that. Why would you say that?” So the kid shut up. And I understood his discomfort about the fact that his kid said something that embarrassed him. And who knows, maybe later he explained to her that gospel is a traditionally Black art form that originated in enslavement. But I kept thinking about how swiftly he shut down her legitimate question because of his discomfort. That, in itself, was a lesson for this child about race.

INTERVIEW: What thinker have you taken comfort in of late and why?

BENNETT: Not comfort, as in makes me feel better, but comfort, as in giving me a language to process this cultural moment. I’ve been digging Lauren Michele Jackson’s essays. She wrote the definitive piece on the problem with anti-racist reading lists as well as this very thoughtful piece for the New Yorker on “the Black voice” in cartoons. She also wrote a fascinating story about attending Robin DiAngelo’s white fragility workshop where she lands on the notion that to be antiracist, white people need to turn toward and away from whiteness but so far, they’re only turning toward whiteness. She writes incisively and beautifully, and she always subverts your expectations.

BENNETT: “Locked Inside” by Janelle Monáe. INTERVIEW: If 2020 were a song, which song would it be?

INTERVIEW: Where did we go wrong? Like, what was the exact moment?

BENNETT: The 2009 VMAs. That was the night we entered this parallel universe.

INTERVIEW: Which (admittedly totally unqualified) celebrity would you trust with the planet’s future?

BENNETT: Rihanna, and she’s totally qualified.

INTERVIEW: If you could stop time at one particular moment in your life, which moment would it be?

BENNETT: Probably when I sold my first book. I was in the car with two of my closest friends when I got the phone call, and that whole drive home was a blur. We’d gone to visit the Motown Museum earlier that day, and I was geeking out like the big nerd that I am, thinking about how happy I was to be there with my friends. And then hours later, I learned that I sold my first book.

INTERVIEW: What’s one skill we should all learn while in quarantine?

BENNETT: I wish I could say bread-baking, but I did not learn a single useful skill in quarantine. Did not bake a single loaf of anything. I think I did learn that I’m capable of adjusting to more than I ever thought I could. So maybe a useful skill is learning how to keep ourselves company, and how to stay in touch with friends who feel far away.

INTERVIEW: What does our future as a nation look like?

BENNETT: Worse before it gets better. One of our two major political parties is united almost entirely around white nationalism and trying to cling to power in what is becoming an increasingly diverse country. Not only that, but this is a party willing to cannibalize itself out of loyalty to Trump. For months, it’s been clear that controlling the spread of the virus and repairing the economy was the only way the GOP could maintain control of the presidency, and yet, they decided to flout health guidelines by reopening prematurely and railed against wearing masks. I have no idea what will come of the Republican party’s cultish devotion to Trump. What can you even make of a political party whose leaders are willing to sacrifice their own lives and those of their voters to appear loyal to the president? But I don’t imagine that fervor goes away quietly, even if he is voted out of office this fall.

INTERVIEW: What prevents you from giving up hope in the human race?

BENNETT: Hate to sound cheesy again but Gen-Z. They have already endured so much as a generation, from growing up in a country where school shootings are normalized, watching viral videos of Black death, experiencing the resurgence of right-wing nationalism, and now this pandemic. And yet they’re willing to fight back against power in a way that is also funny and self-aware. I know everyone loves to mock the generation coming after them, but I will say, in my embarrassingly millennial sincerity, that I’m rooting for Gen-Z and I’m excited to see the world that they will create.

INTERVIEW: Who should be the next president of the United States?

BENNETT: Not even going to be cute about it, I’m voting for Joe Biden. I would vote for nearly any human alive over Trump.