The War on Drugs Get Lost and Found

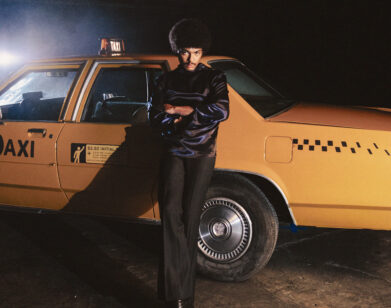

ABOVE: THE WAR ON DRUGS’ ADAM GRANDUCIEL. PHOTO COURTESY OF DUSDIN CONDREN

The War on Drugs have never been afraid of stretching out, but on “Under the Pressure,” the expansive opening track to the band’s latest record, they seem particularly comfortable in the process. The nine-minute number starts with a flurry of nervous electronic rattling long before the piano kicks in, shepherding the kind of open-road soundtrack that has become The War on Drugs’ calling card. Over the span of those nine minutes, the band slowly reveals its arsenal: big, driving drums and keyboards are punctuated by the occasional saxophone burst, while soaring guitar lines take off alongside frontman Adam Granduciel’s rambling tenor. Rather than land on a high, though, “Under the Pressure” draws to a close over a long stretch of pulsating distortion. It’s an absorbing move, indicative of a band hitting its stride.

Lost in the Dream is The War on Drugs’ third and easily most anticipated album to date, but in many ways it also feels like their first. Following 2011’s breakthrough, Slave Ambient, Granduciel and bandmates Dave Hartley and Robbie Bennett struck out on a tour that would, upon completion, stretch the length of two years and well over 100 shows. During their time on the road, Slave Ambient‘s songs grew and morphed into something wholly new, and Granduciel found himself staring down an increasing amount of critical praise alongside a band at the height of its capabilities. With the strength of touring behind them, The War on Drugs spent the bulk of 2013 jumping between six different studios to work on Lost in the Dream. The result is an album that makes unmistakable nods to America’s greatest rock heroes—Springsteen, Dylan, Petty, Simon, and Young—all the while highlighting Granduciel’s particular brand of painstakingly layered song craft, and band’s newfound, vibed-out comfort zone.

Below, we chat with Granduciel about the post-tour comedown, studio hopping, and the heady meaning behind Lost in the Dream.

ALY COMINGORE: You guys had quite a run with the last record. What did coming home to Philadelphia look like when that finally hit an end?

ADAM GRANDUCIEL: It was intense. Touring is a rough thing. You don’t have any time to look around or stop and think if what you’re doing is making you happy. The more you tour, the better the band gets, and you get caught up in a lot more things than just traveling. It becomes a way to survive. It was definitely strange to come home and all of a sudden have to shift gears into creative mode. I kind of had to figure out what it was about music that made it exciting, and question what it was that made it worth sacrificing all the other parts of my life that weren’t as satisfying.

COMINGORE: You had to decide whether or not it was going to be a career.

GRANDUCIEL: Exactly. We had a choice on the last record, I think. We could have come out and been well received, but maybe not toured for two years. Or we could have done what we did, which was pretty much consistently tour and scrape away and have turmoil in each of our personal lives because of choosing to do so. But in the face of that we became a better band in front of a lot more people. That touring cycle was kind of the birth of the band. Even though we were all friends, we kind of reached a new level of friendship over the last couple years. I realized that it’s rare in life to look at all the people around you and realize that they’re all invested in what you’re doing.

COMINGORE: How did the writing process for Lost in the Dream compare to the last two records?

GRANDUCIEL: I was definitely a lot more disciplined. I didn’t want to do it like I did the last record, which was just me putzing around with a bunch of loops for three months and driving around high in my van coming up with melodies. That was something that I was able to do when I was doing it, but now, I don’t know, you just grow up a little bit. You want to do things a little more professionally.

COMINGORE: But you were still demoing a lot of stuff at home first.

GRANDUCIEL: Yeah. When you’re in the moment and not over thinking the song is when things tend to really work. You’re not so focused on the minutiae. You’re focused on the overall feel, and that’s the stuff that I get from the demos. First impressions are always the most important. When you start getting into a full-band, democratic context the little things almost immediately get thrown out the window because you don’t think they’re important.

COMINGORE: Do you know what you’re going for when you press “record”?

GRANDUCIEL: Sometimes. I usually know the general emotion of a song, or the general feeling of it, and then I think I just get so excited by the act of recording. I love that process so much that I feel like if I knew exactly what I wanted I’d arrive at something too soon. Part of the reason I work on stuff for so long is just because I love working on it. It’s not that I’m haunted by some ghost sound. I just have nothing else to do with my life. Some people like to obsessively shop online. I like to obsessively rack up studio bills.

COMINGORE: And you guys were in and out of a lot of studios.

GRANDUCIEL: It was like seven studios, including my house and my friend Jeff Ziegler’s house in Philly.

COMINGORE: You were also in Asheville.

GRANDUCIEL: Yeah, we went to Echo Mountain in Asheville twice. They’re like the Nordstrom’s of online shopping. I wanted to go down there just to get out of town for a little bit, but I realized that if you bring people out to a studio they’re kind of forced to care about your songs, if only because you’re the one who’s going to buy the burritos. If you tell them you’re going to put all the liquor on the band expense, they’re like, “Fuck yeah, I’ll go to Asheville with you.”

COMINGORE: Where else did you guys end up?

GRANDUCIEL: Then the other studio was with Mitch Easter. He produced a lot of early REM records and a bunch of other weird Southern pop rock stuff. He has a studio in North Carolina that I had heard about, so we went there. I’m a bit of a gearhead, so I like checking out what people have. And growing up as a fan of rock music and rock-‘n’-roll myth, I realized that this is maybe the only time in my life that I can have, by today’s standards, a really large budget for a record. My thought was, well, I can live in fear and make a tiny bedroom record… But this band needed to make a bigger sounding, high-fi professional record.

COMINGORE: One thing that struck me immediately is that it really feels like one big piece of music.

GRANDUCIEL: Yeah. I always work on the songs all together up until the very end. I never mix a song and think, “Okay, now that one’s done.” I think that’s why it feels like songs are really connected, and I like that. They’re all worked on kind of like a little family.

COMINGORE: And the record is kind of your kid.

GRANDUCIEL: [laughs] I love when people will say, “Oh, my songs are my children.” I understand that, but I’m also not afraid to kill my kids. I know when the time has come to throw it in the trash can. [laughs] With a child you’ve got to go to therapy and put it in daycare and buy it birthday presents. With a song, you can shove it in a dark closet and tell it you’ll be there when you’re ready.

COMINGORE: Do you feel like there were albums or artists that were especially influential to the process?

GRANDUCIEL: Yeah, definitely. For me to make the kind of music I make and say things like, “I don’t even really listen to Bruce Springsteen,” I mean, that would just be silly and embarrassing to read. I definitely admire all of those people and then some. Even Neil Young, who isn’t really evident when you listen to my music, is probably my favorite of the legends, besides Dylan. They’re all a huge influence on me. For me, just following rock history and watching Darkness On the Edge of Town and realizing that’s it’s okay to be obsessed with a snare sound because Bruce Springsteen was obsessed with a snare sound.

COMINGORE: I want to talk a bit about the album artwork. The cover is a picture of you in your house, right?

GRANDUCIEL: Yeah. All of the artwork is pictures of my house. So much music was made here over the last 10 years: all the War on Drugs stuff; me and Kurt [Vile] have made a lot of music in this house; friends have recorded their songs here. I wanted to immortalize it in some way on record. It has been such a big part of my musical journey in Philadelphia. I think it’s been a part of a lot of other people’s musical journeys, too, just because it’s this big house with no rules. You can practice here. I have my studio here. You can smoke inside. It’s the fuckin’ fun zone.

COMINGORE: I heard a rumor that there’s a short film about you and Kurt floating around somewhere.

GRANDUCIEL: [laughs] Wow. I hadn’t thought about that in a long time. Yeah. In retrospect it would probably be really fun to watch it. I think it would be a lot more revealing in a lot of ways then I thought about at the time. Mine and Kurt’s relationship is a really special moment in my life and in my musical journey. Finding someone at that part of my life, when I was really ready to dive head first into making music I thought was interesting, it was a beautiful kismet. I think he needed someone who was going to go on that journey with him and open up a space and make life about recording and having ideas and jamming. On my side, I think it was important that I saw somebody that knew how to express himself through music in a different way. I see that movie as an early glimpse of people being naïve, and how in friendship people can be so close and yet so different at the same time.

COMINGORE: As far as the album title goes, I feel like “Lost in the Dream” can either sound really idyllic or kind of dark and disillusioned. What was your intention when you settled on it?

GRANDUCIEL: For me, “Lost in the Dream” is about feeling disconnected from everything—your life, your expectations, your romantic relationships—and trying to make something in the face of that feeling, but also about it. A lot of the songs—”Under Pressure,” “Suffering”—I wrote when I wasn’t thinking about myself or the bigger picture, but six months later they really formed what the album turned into. It’s definitely autobiographical, but it’s also about trying to put those feelings that I know everyone has into the kind of art I want to make.

THE WAR ON DRUGS’ LOST IN THE DREAM IS OUT TOMORROW, MARCH 18, VIA SECRETLY CANADIAN. FOR MORE ON THE BAND, PLEASE VISIT ITS WEBSITE.