IN CONVERSATION

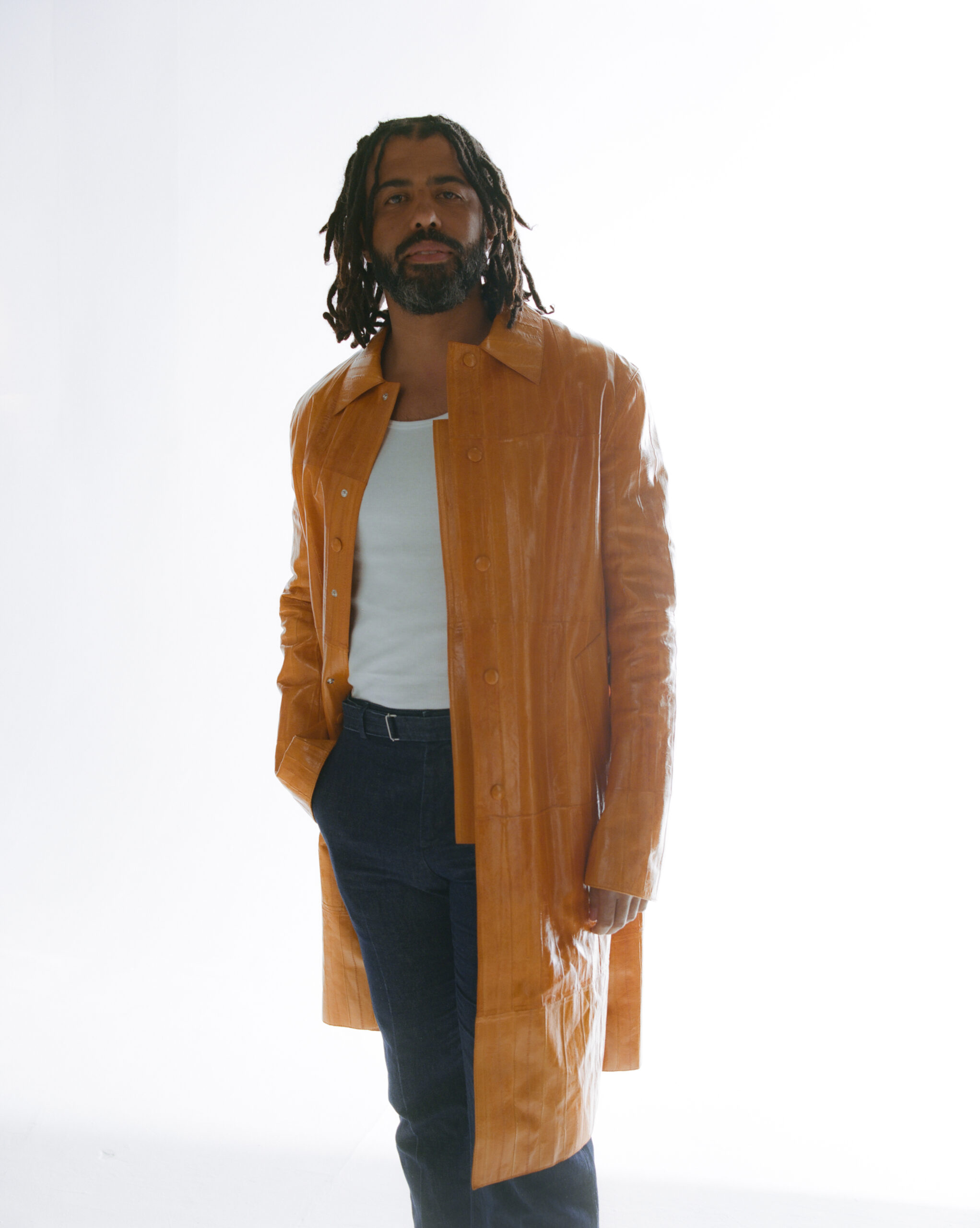

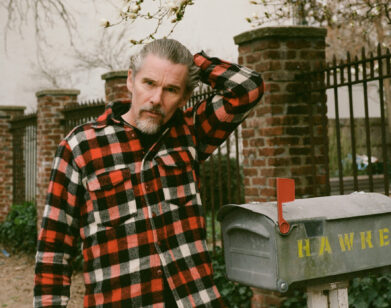

Daveed Diggs and Ethan Hawke Just Want You to Feel Something

Jacket and Shorts Amiri. Shirt Calvin Klein. Sunglasses Givenchy. Rings and Socks Digg’s Own. Shoes Camper.

Daveed Diggs, the handsome multihyphenate and 2016 Tony Award winner for his dual role as Marquis de Lafayette and Thomas Jefferson in Hamilton, is about to make his way from a film set in Vancouver back to Los Angeles when he and Ethan Hawke hop on a call. “You’re the next Paul Newman,” Hawke tells his friend and The Good Lord Bird co-star, and you can hardly blame him for the lofty comparison. Since exploding onto the scene in the megahit Hamilton, the 41-year-old Diggs has written and directed his own film, 2018’s Blindspotting, which Hawke calls “the definition of an indie, cool, badass movie,” and played a Rabbi in the recently concluded anthology series Extrapolations. He’s also in an experimental rap group called Clipping, which was tapped by the Disney Channel to write a “Hanukkah banger” in 2020. The house of mouse came calling again more recently, as Diggs was cast to voice the notorious Sebastian in Rob Marshall’s forthcoming remake of The Little Mermaid, in which Diggs performs an electric rendition of the classic “Under the Sea.” Before he hit the road, Diggs and Hawke got on a Zoom call to talk about life as a celebrity, their shared craving to return to the stage, and the importance of making creative choices guided by personal taste.

———

ETHAN HAWKE: Hey, bud.

DAVEED DIGGS: What’s going on, man?

HAWKE: Not too much. How are you? Where are you?

DIGGS: I’m good. I’m in Vancouver finishing up a movie. About to drive back to L.A. That’s a drive I really like doing.

HAWKE: So you just wrapped?

DIGGS: Yeah, yesterday.

HAWKE: I like that Vancouver-L.A. drive.

DIGGS: Yeah. It’s really very peaceful.

HAWKE: Are you going to stop anywhere on route?

DIGGS: I am. I always stop in Portland and then home in Oakland.

HAWKE: So how long will it take?

DIGGS: Three days, probably. I might spend an extra day in Oakland. I haven’t seen my family in a little bit, so we’ll see.

HAWKE: Right. So are you in some temporary hotel?

DIGGS: I’m in an Airbnb in the Commercial Drive area, if you know the city.

HAWKE: I do. The funny thing about shooting movies is sometimes it almost doesn’t matter what city you’re in, the B&Bs or the Radisson Hotel. I remember once I was in China and David Carradine was in the hotel. You remember crazy David Carradine? Well, I said, “How do you like China?” He goes, “I’m not in China. I’m making a movie. Director is nervous, actors are crazy, hotel is fantastic. I could be in South Carolina.”

DIGGS: [Laughs] You’re at home. I know because I love this background. This is my favorite Zoom background. We did so many pandemic Zooms together.

HAWKE: I know. Did I ever tell you the story with this background?

DIGGS: I don’t think so.

HAWKE: It’s a giant mural covering the whole wall. Richard Linklater made it for me. He took Polaroids of the heads and tails of films. He runs the Austin Film Society, and so he made this giant graphic thing.

DIGGS: That’s so cool.

HAWKE: Isn’t that cool? Well, all right. So I’m supposed to interview you, Daveed, and I take my job incredibly seriously, okay? You may not know this, but I made a documentary about Paul Newman and you’re the next Paul Newman. I’m beginning my documentary about you. Okay?

DIGGS: Let’s go. Let’s go.

HAWKE: Your life before you were a big shot and your life after you were a big shot, right? In what way do you feel a demarcation in your life? And has it changed the way you moved through space?

DIGGS: It has. I mean, I have money, which is cool, that was not true before and it is true now. So my vacations have gotten better. I did things like buy a house. Those sorts of financial stresses have been replaced by new, more existential stresses. But in terms of how I move through the world, I don’t know that it’s changed a lot. I think I work with so many of the same people most of the time. You know what I’m saying? So really, the way we work certainly hasn’t changed. I still talk to Rafael Casal every day about the ten to fifteen ideas we have at any given time together. Probably the majority of the time I spend thinking about art is thinking about it with that guy. My close friends are still my close friends. It’s just sort of interrupted by these moments of press tours and things that feel like I’m inhabiting a different person’s life for a while.

HAWKE: You said something that I think about a lot. My daughter, Maya, is on that show Stranger Things. So she’s watched her parents deal with celebrity but she’s never experienced it for herself. One of the biggest things I wish for her is in your answer, that if you have real friendship, like real friendship, then it gives your life ballast. First of all, we’ve got to say, I mean, what a wonderful man that guy is.

DIGGS: Yeah.

HAWKE: I meet very few grown-ups in the world, and I know he is a young man, but he has always carried himself. He takes care of others on set. A lot of people get extremely selfish when they’re creating, and they feel like they have to get selfish, and the world will give you permission to be selfish. I’ve been moved by your friendship.

DIGGS: I mean, he’s obviously among the best people I know. And yeah, he does do that. He’s a real creatives’ creative, and he’s been in all those spaces. It’s why he’s a good showrunner. It’s the way he works on Blindspotting, people leave there feeling like they’re able to be their best selves on that show, and that has a ton to do with the atmosphere he creates.

HAWKE: When I first saw the movie Blindspotting, you guys were the definition of an indie, cool, badass movie. I mean, there we were at Sundance. There’s certain lanes that filmmakers go into. There’s, “Are you trying to make a movie that plays at Sundance? Are you trying to make a movie that wins an Oscar? Are you trying to make a movie that makes a hundred bucks?” What lane is your aspiration in? What’s the difference between making the show as an indie rock star stud movie versus trying to sell it to America through a streamer?

DIGGS: Yeah, man. I mean, I think we were in our 30s by the time we made that movie. I still don’t understand. I agree that those lanes exist, but I could not tell you how to do any of those things, including being a rockstar indie filmmaker. It took us ten years to write a movie, and the only reason it ever happened is because our producers, Jess and Keith Calder, insisted that we do it. So, turning that into a TV show, this is the thing about working with the same people, right? We have a way that we work on things and a way that we get excited about things, and that enthusiasm carries the artistic ship across the finish line. The fact that Starz wanted it is shocking to me, but they did, and then they did let us do it.

HAWKE: The show is so creatively free, with spoken words. It’s so playful. I admire the show so much. I kind of can’t believe you got it made.

DIGGS: I agree. Sometimes we have these long conversations with the marketing department because you’re right, you’ve got to sell a thing to America as a thing. I don’t know how to do that. I know how to write or read a script that I think is good. I know how to get excited about whatever I’m working on as an actor. I know how to start making a song and keep working on it until it gets to the thing that it was supposed to be. I know how to do that, but in terms of the categorizing of things, I don’t know, and I never really have had a sense of that.

HAWKE: I think that’s why I like you so much, Daveed. I feel the same way. I hear these stories about some rockstar that right in front of their treadmill they put a picture of a Grammy, you know?

DIGGS: Yeah.

HAWKE: I don’t know how to even want that. I mean, it’s not like I don’t want compliments and prizes and money and fire engines. I want everything, but I know how to listen to the river, how to listen to my own voice. I remember when I was doing those movies with Richard Linklater, for example, the Before Trilogy or Boyhood, I didn’t even know if they would come out. One part of my brain thought, “Oh, people are going to love this.” And another part of me thought, “Nobody’s going to be interested in this.” I didn’t care. I knew that I was interested in it, and I can hear that voice. But every time in my life I try to sell out, when I’m like, “Oh, that’ll be a hit,” every time I try to do that I fall on my ass. Totally wrong every time.

DIGGS: Yeah. Sometimes I wish I was one of those people, but I’m just not. I’ve come to terms with that over the years.

HAWKE: I wanted to ask you what you think about this. I’ve spent the last nine months working on a movie exploring the life and work of Flannery O’Connor, who is this Southern gothic writer. One of the things that’s interesting about her artistic life is she didn’t have any meaningful success until after she was dead. She was always writing for herself, or a tiny fraction of the population that read the Partisan Review. She had this line where she said, “Well, I’d rather have one reader in 100 years than 100,000 today.” It’s a very interesting thing to think about when you make things. Are you making them for yourself? Are you making them for other people? I always feel like Bob Dylan’s being true to himself and millions of people happen to care. Spike Lee seems to always be working for himself and some of the movies hit big and some of them don’t, but you can tell they all kind of mean the same. It’s coming from the same creative force. When you make music, do you think about who you’re singing for?

DIGGS: Well, I think about the audience, right? I do think about how I want to elicit a feeling from people. I am going for that. I’m not just making it for myself. I’m aware that I want other people to listen to this. But it’s also guided by my band, it is guided by our own impulse and excitement. I don’t think of myself as one of those artists who doesn’t want care whether people listen to the thing. I do care, I definitely care.

HAWKE: Me too.

DIGGS: The fun part is that at some point I’m going to share this with somebody and I do hope they like it. I’m not going to be devastated if they don’t. Generally speaking, if they don’t, I understand. I’m making choices with that in mind. “I think this bridge feels cool here. I think I chose these words because they sound cool to say.” I want you to sing along.

HAWKE: You’re trying to connect. I feel like the best part of me when I’m working is when I’m trying to be true to myself so that I’m not talking down to said audience member. You’re trying to build something honest.

DIGGS: One of the things I love about being an actor, on the occasion that I just get to act in something, is I do feel like I get to be creatively the most selfish. I am responsible for this character’s journey and definitively not responsible for the rest of it. Whereas in filmmaker mode, I think you are the one who has to think about that connection. You have to be aware of the audience and modulate everybody’s performance to that.

HAWKE: I think that’s why I love acting. When you’re responsible for everything, there’s a certain pride you can take in it and respect you can have from how hard it is to do. But the joy I have from acting is actually just my little piece of the puzzle and saying, “I’m going to offer this up to the universe to make of it whatever they will.” In this new piece you’re playing a rabbi, right?

DIGGS: Oh, in Extrapolations. Yeah, yeah.

HAWKE: I find that kind of interesting because I did First Reformed where I was playing a priest. I kind of loved that we both got to play a serious, well-meaning person of faith.

DIGGS: It was cool for me too because I was raised Jewish, but I have my own general feelings about religion and how it tends to function in my own prejudices about organized religion in general. So getting to play somebody that kind of forced me to reinvestigate the faith that I was raised in, also a person who was in conversation with that faith in a really real way as it related to the real world, and was a good person trying to do the best that they can. [That was] fun to do, also.

HAWKE: Did you ever read James McBride’s Color of Water?

DIGGS: I never read Color. I think I’ve read all of his other books, except the one.

HAWKE: Color of Water is really, really beautiful. His mother’s Jewish. He writes very beautifully about that. I had a lot of people in my life when I was growing up who were very, very serious about their faith and you very rarely see it on film. Yet all those people in my actual real life were sources of inspiration to me. What’s the relationship to the community of African Americans who are Jewish? Is that a big population?

DIGGS: I imagine it’s bigger than we would imagine it is. I’m from the Bay Area, so I was definitely not the only Black Jew I knew growing up, but also maybe that’s particular to the area I was from. I remember being sort of a novelty to folks I went to college with. So that was always interesting to me. Yeah, we out there, there’s plenty of us. I don’t know. Me and the guys from Clipping made that “Puppy for Hanukkah” song a couple of years ago because, weirdly enough, the Disney Channel reached out like, “Hey, we want a Hanukkah banger.” I don’t know that this weird aggressive band is the one to make that, except that we totally were the ones to make that. We had a lot of fun with it, but I remember when it came out, there was a lot of discussion online about it—about how great it was for representation of Black Jews and a lot Black Jews coming to me in my DMs. I’m happy for the representation opportunities that it presented for a lot of people.

HAWKE: How often as an actor is it meaningful to you when you get offered parts that could be written for a person of any skin complexion?

DIGGS: I mean, I think it’s just meaningful to me when I get offered parts that are my taste. When someone sends me a script that’s an offer and I read it and the ethnicity of it doesn’t matter, but I read the script and I’m like, “Oh, I really love this thing. This is really my taste.” That is really meaningful to me because for some reason I feel like it implies that for either my body of work or the way that people are talking about me out there, someone had to know that it was a good idea to send me this thing and that I would like it.

HAWKE: Yeah, it makes you feel a little known. I think most of us go through the world worrying that nobody sees us, really. Every now and then I’ll have that experience. I mean, I felt that way with First Reformed, the idea that Paul Schrader would think of me for doing this, because actually, I related to everything that character was going through. I think you can bring that to set in a way that’s really exciting.

DIGGS: Yeah. Well, when you came to me with Good Lord Bird, I’ll never forget the feeling of it because you gave me the book, which I hadn’t read yet. You were very cautious. “Hey, this is a particular take. You got to read it first and let me know.” I have almost never felt more seen than being suggested that book to read. That book is so deeply my taste, and then the fact that you would ask me to play Douglass, that was also not a thing that I would’ve expected to be offered. It was like, “Oh whoa, Ethan Hawke is inside my head.”

HAWKE: When I asked you about this other part in Good Lord Bird, you were like, “Well, I think my best friend’s the perfect guy.” And it made me like you so much that you are moving through space championing your friends and championing the people that you believe in. Then funnily enough, when Rafael arrives on set, he has to maintain a quality level that you have established. He knows a friend of his stood up for him and that you had a big impact on that film. But people have this idea that working with your friends can be a mistake, but not if you have good friends.

DIGGS: Yeah, exactly.

HAWKE: So, what’s the thing you just finished?

DIGGS: It’s called In the Blink of an Eye. Andrew Stanton’s directing.

HAWKE: Oh, wow. He’s great.

DIGGS: Such a great guy. Got to hang out with Rashida Jones a bunch. We spent a lot of time together in the film. She’s fantastic. It’s like a really sweet film, a really beautiful script. I don’t know how much I’m allowed to say about it. It’s a cool meditation on relationships and technology and it’s beautiful.

HAWKE: I’ve known Rashida for a long time. She’s a really special person. It’s kind of amazing where she comes from. I mean, she’s entertainment royalty.

DIGGS: We spent most of the time talking about music, like 90%.

HAWKE: She must have a very interesting take on music. I mean, because she’s coming from inside the hive. I mean, she’s seen it at its highest form.

DIGGS: You’re in the studio when “Thriller” is being recorded.

HAWKE: Also, you’re doing The Little Mermaid. I’ve gotten a little of all the things you’re doing. I mean, that’s kind of interesting. My whole life as an actor I’ve dreamed of getting some email saying, “You can audition for the voice in one of these.”

DIGGS: You’ve never done a big [animated movie]?

HAWKE: I’ve never done one. Nobody’s ever come.

DIGGS: Shocking.

HAWKE: I watch all these movies and I’m like, “Oh, I could do that guy’s voice.”

DIGGS: Oh man, that should happen tomorrow. What do you mean? This is now my mission.

HAWKE: You’re playing the crab.

DIGGS: Yeah, I’m playing Sebastian. It was insane. It was so much fun to work on. The other thing about voice gigs is you’re pretty much in and out of there, but the great thing that you would’ve loved about this is that we rehearsed it like a musical. We spent a month in London, the whole cast together rehearsing the thing. So even though I was just going to be a voice, at the end of this rehearsal session I recorded all my stuff and left and they still had a year-and-a-half of filming left that they were using my already pre-recorded takes with puppeteers to work with the actors. That rehearsal time that Rob Marshall insisted on was so lovely. I haven’t seen the film yet. I’m going to see it at the premiere.

HAWKE: And when’s the world going to get you back on stage?

DIGGS: Man, I am actively searching. I’m trying to get back there. I haven’t found the thing or the timing yet, but yeah. You saw White Noise, right?

HAWKE: Yeah.

DIGGS: That was the last thing I did. That was the first thing I had done since Hamilton. I went back to my team and was like, “At least one a year, guys. I’ve got to do one play a year.” And then the world shut down.

HAWKE: That’s how I feel. Right before Good Lord Bird I did True West and I haven’t done a play since then. I don’t think I’ve gone 18 months since I was a kid without doing a play. I’m starting to kind of crave it like water, you know?

DIGGS: Yeah, me too.

HAWKE: I read something the other day that if you’re in New York, there’s a crazy early Sam Shepard play called Tooth and Crime.

DIGGS: Oh, yeah.

HAWKE: It’s about the war of ideas, and it’s kind of a young musician and an older musician, they have poetry battles. He wrote it before there was such a thing as a rap battle, so it’s not written like a rap battle. They’re almost country western battles, but there’s just spoken word. It’s almost Shakespearean meets Baudelaire, and I kept picturing you in it. And I was like, “Shit, next time you’re in New York, we should set up a reading.” Because it’s the kind of reading you should get. Because this play was written as part of the whole ’60s revolution when he is hanging out with Patti Smith and they’re doing all this punk rock shit. It was back in the days when people were trying to turn off the audience. Their plays are a giant fuck you to the audience, but there is something sexy about them. It makes you want to party, it makes you want to dance, it makes you want to run and it’s really alive. Some time we should do a reading of it together. The language is so difficult, but you could do it well and lift it and make it modern.

DIGGS: Whoa, trip. Let’s go, man. I’m about to go get myself a copy of this play on the way home.

HAWKE: I’ve done a bunch of his work and you can make sense out of it.

DIGGS: Right, right.

HAWKE: It wants to be an event. He used to say a theater show should be like a rodeo. I saw an early preview of Hamilton when it was at The Public, and I saw it again on Broadway. And even watching that play’s success impact the event of seeing it. I saw it before you guys opened and there were people sitting in front of me that actively hated it. They left at intermission because they hadn’t been taught yet by society that this was good. And once it got to Broadway, everybody was fighting for tickets so much. I mean, they were applauding before you guys started.

DIGGS: The whole journey of that thing was amazing, improbable, and wild. I’m so grateful for all of it, obviously. But the fact that someone would walk out is awesome, right? It’s not for everybody, and that’s one of the things that’s nice about it.

HAWKE: And that’s kind of magic and awesome about it and you don’t want to give that up. I remember I had a funny experience once where I was doing a new Stoppard play and Stoppard’s a big smoker. So at intermission, he’s out there chain-smoking, hiding from the audience, and he’s sitting with the director and he notices groups of people not going back in at intermission and it really hurt his feelings. He’s like, “Why don’t they like it?” And the director who was sitting next to him with us said, “You know, we had about 10% walkout when we did Hamlet.” And Tom goes, “They walked out of Hamlet?” And he is like, “See, you know, there’s no accounting for taste.”

DIGGS: It also is so lovely to hear a story about Stoppard being sad that people were walking, because you read his stuff and you’re like, “Of course you don’t care whether anybody likes this or not.” Artists, we’re all the same. We all desperately want people to like what we make, of course.

———

Grooming by Colleen Dominique using MERIT Beauty and Caldera + Lab at Exclusive Artists

Stylist Assistant: Lyn Veliz and John Celaya

Production Assistant: Benjamin Rigby

Special Thanks to Solar Studios