Strand of Oaks, In The Thick of It

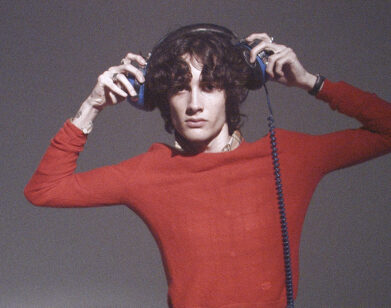

ABOVE: STRAND OF OAKS’ TIMOTHY SHOWALTER

When we met Timothy Showalter, who records as Strand of Oaks, for a beer in New York last month, we noticed his new tattoo: “SURVIVE,” in capital letters, inked by his friend Josh Stephens and spanning most of his right forearm.

The motivation behind it was practical, at least in part: “I didn’t want to cut my arm anymore when I got drunk,” Showalter says. But the word itself was one of only two possible options to commemorate the last three years of Showalter’s life. And he’d already used the other one, “HEAL,” as the title of his epic, explosive fourth album, out this week.

When talking about music, the word “powerful” often becomes shorthand for “affecting,” and HEAL is. The pain and trauma Showalter works through on the record, which he wrote in a manic state immediately after suffering a mental breakdown at the end of a nonstop two-year tour, are evident throughout, and are easy to identify with: loneliness, hurt from the past, and fear of the future, in their rawest states. But HEAL is powerful on a more literal level, too. The driving, hard-rock guitar riffs, courtesy of J Mascis, that open the album feel physically present, defiant, strong; and for the next 10 songs, the sense of urgency doesn’t let up, even as Showalter nimbly moves between genres.

“What’s funny is after it’s all said and done, it’s music that I wanted to make anyways, but I never planned for it,” Showalter says. “It’s like four records that I wanted to make in the future, combined into one. I wanted to make that synth-y dance record, I wanted to make that really loud metal record; they just kind of all rushed themselves into this.”

Showalter describes the process of making the album as something like a trance, over which he had very little control; and when we talked to him in May, it was just a few hours before many of his friends would be hearing the music for the first time, at a show at Pianos.

TIMOTHY SHOWALTER: Previously, I shared records with people to get a tasting of: “Please tell me if I’m insane or not.” This was the first one where I just was like, “Nope. I do not give a fuck. This is what I have to do, beyond any control.” My best friends haven’t heard it.

ALEXANDRIA SYMONDS: So tonight is going to be the first time?

SHOWALTER: Yeah. I am just so scared of someone to criticize it that I just refuse good or bad opinions. Because with your friends, you can’t trust them. They’re not going to tell you. My wife is the only person who will be like, “I don’t think that sounds good.” And then I get mad at her. I’m like, “That’s like telling an infant that they’re ugly.” You can’t, it’s a new baby! Especially in demo process. If a song could walk down the street naked, it’s like what a demo is. It’s so fresh! You can destroy this thing if you say something wrong. I know some artists are opposed to talking about stuff, but I need to have conversations about it, because it’s such a manic creation that I haven’t made sense of it yet.

SYMONDS: Is this one of your first interviews for it?

SHOWALTER: Yeah, basically. There’s no canned answers yet. It was like a fever dream. It happened so fast; I have no idea how it was made. I know why it was made, because it needed to be made, but it was such a visceral process. It wasn’t calculated.

SYMONDS: You said in an email that you felt like this album represented your brain breaking up with itself.

SHOWALTER: You have breakup records, and I’ve written a breakup record, but this is a record where I feel like… [pauses] I no longer knew who my self was. It sounds narcissistic, but I had no idea who I was. There was this breaking point—and it’s like a relationship ending—where my brain just stopped tolerating me lying to myself and stopped allowing me to continue to hide and push down bad thoughts and painful things. It was just like the legs gave out, and it fell apart. It happened on stage in Sweden.

SYMONDS: There’s a specific moment you can point to?

SHOWALTER: Yeah, I was singing a song, and I might have had too much whiskey, but my tour manager said, “You added, like, two different verses on that song.” I was like, “I don’t remember doing that.” Then I panicked, and I was like, I think I’m disconnecting here. I have [family] history of mental illness and I was like, “Is this when the schizophrenia sets in?” It was like a psychedelic drug experience, but I didn’t do any drugs. My brain chemistry just wore out, trying to be like, “You are denying all of these things you need to deal with.”

SYMONDS: Do you feel like things transpired to bring you to that point? Or it was more like starting to realize as an adult that you are living the same things over and over again? Did things change, or was the problem that things hadn’t changed?

SHOWALTER: Things hadn’t changed.

SYMONDS: There’s a song on the record that gets at that: “Most days I end at the same place where I begin…”

SHOWALTER: Yeah. I realized that things weren’t changing that should be changing, but I also left for tour for two years. And touring is the best way to run away from your marriage, your alcoholism, your drug use. You can be on that pirate ship and you’re not accountable. Touring is the only place where I like myself, because when I’m home, it’s just like an endless cycle of like feeling like a loser, feeling like I’m eating shit and drinking too much. When I had that breakdown, I knew that my tour was ending and I had to year to make a record.

SYMONDS: And that was at the tail end of the full two years of touring.

SHOWALTER: Yeah, it was like the second-to-last show of basically touring since 2011. It was a fear, because I was like, “I’m going to go home to a house I don’t know, to a domestic situation that I am completely unsure about, and I’m doing nothing to make it better. I’m not being active at all.” My drummer at the time was talking about being excited to go home, and I was like, “I want to do this forever.”

SYMONDS: What you’re saying sounds like how people describe struggling to readjust after coming back from war. You get thrown together with people for a common purpose that is not organic to the way that life happens normally.

SHOWALTER: Yeah! I’ve spent more time with my tour manager than my family, combined, since I was 18. I’ve seen this person for more hours than everybody I grew up with.

SYMONDS: It’s strange, also, to be doing essentially a really familiar thing, over and over, but in this variety of both foreign and dissociated-from-yourself landscapes.

SHOWALTER: Exactly.

SYMONDS: Everyone who comes to your shows knows and loves your music and knows you, but you don’t know them. You don’t have any responsibility to them beyond just…

SHOWALTER: Yeah, putting on a good show. And I need to have purpose in my life; if not, I just disintegrate. It needs to be a goal-oriented end. I feel really good when I wake up and know I have to be there at 5:30 and play at 10. It gives me strong purpose, and without that, I got home from that tour and I just crashed into alcoholism, I crashed into drugs. But it was also fueled by songwriting.

SYMONDS: Did you start writing immediately when you got home?

SHOWALTER: Yeah, I wrote like three of the songs… I wrote the song “Heal” like six hours after I got home from the flight.

SYMONDS: You came home, kissed your wife, put in a load of laundry, and started.

SHOWALTER: Yeah, boom. My wife probably wanted to leave me every day. It’s cool to say on paper that I was in a manic episode, from an artistic and a cool record standpoint, but I was hell [to live with]. I didn’t leave. I went on walks in my little neighborhood, but I didn’t go out, I didn’t call people; probably when I spoke on the phone it was even more disjointed than what I’m saying now. My friend said it’s like turning on a faucet; the crazy faucet got turned on. I also need to be careful, because I don’t want to discredit the really magical thing of making music by saying it’s crazy.

SYMONDS: I’m sure there’s a less loaded word.

SHOWALTER: Yeah, because it’s not crazy. I was in pain, and my brain was doing stuff; I don’t know what it was doing. But I was just talking to somebody and they said, “The last form of magic in the world is making music,” and that’s true for me. That sounds corny, but I don’t give a fuck. I don’t know why I wrote the songs; there was no intention of, “I’m going to write this song about travel,” or, “I’m going to write this song about an issue.” And it came out, also, with the style of music. I just don’t know what drove me to do it. It’s definitely a risky record—it’s not something you can put on a coffee shop. There are so many records out now like, “Aw man, I can kind of hear a snare drum, and a little synthesizer…”

SYMONDS: No, this comes at you like a freight train. I think it’s fucking awesome.

SHOWALTER: I hope so, because it’s also 45 minutes of like, there’s not a breath. And I don’t doubt the record, because it’s my favorite; I’m almost scared of how much I like it. I’ve never liked anything I’ve done, and I like this.

SYMONDS: Really?

SHOWALTER: I listen to it and feel like I didn’t even write it—even to the point where there’s guitar solos in a song that I can’t play again. “What did I do there?” I was even crazier in the studio. Right now, I’m speaking to you and I’m thinking about parking, I’m thinking about my checking account. I don’t sleep at night, I can’t stop thinking about this stuff. The studio and enough marijuana allowed me to be like, “I just keep thinking about this one bass line and that’s all. This feels so fucking good!” And then it goes away, and you can see when the haze is leaving, and stuff starts creeping in: “Agh, I forgot my dad’s birthday!”

SYMONDS: The worst thing about a comedown is being aware of it. As soon as you start to think, “Oh, this is where this ends…”

SHOWALTER: Yeah, that it’s leaving you. A lot of my friends are getting sober, and I’m in the process of asking how much they drink a day, and I’m like, “If they drink a lot less than me a day and they’re needing to get sober, what is going on?” I’m overweight and not healthy and I just always wonder, “What am I doing wrong here?” I don’t know. I lost track of a lot.

SYMONDS: I really wanted to talk to you about the opening cut, “Goshen ’97”. That song is about being a kid, being super isolated, listening to records. The experience of loneliness changes the older you get, I think. That’s a kind of loneliness that feels almost good in retrospect, once you’ve experienced what it’s like to be lonely as an adult.

SHOWALTER: Yeah.

SYMONDS: It’s just circumstantial, when you’re a kid. How has that feeling evolved for you, as a person?

SHOWALTER: I had some health problems when I was younger, and was misprescribed some medication when I was 12 or 13, and it switched my brain into mega-depression mode with puberty.

SYMONDS: And being 12 or 13 on its own…

SHOWALTER: It’s already bad enough, and I was a not-normal kid in a very small town. But there was a fantasy of loneliness and sadness that I had as a younger kid. I loved sad music, I loved sad movies, I wanted to be sad.

SYMONDS: The romantic melancholy. You wanted to wonder around the moors.

SHOWALTER: Yeah, exactly. I wanted to read Catcher in the Rye 100 times. There was this fetish of, “I am going to be lonely” and “I’m not going to this party, with girls; I’m going to be this guy.” And what’s sad now is in my adult life, in my 30s, I can’t listen to sad music or watch sad movies, because I’m like, “Life fucking sucks! I don’t want to fantasize.” I want to watch shitty comedies and listen to Grateful Dead and try to dig myself out of that pit.

I had a bad teenage life. It wasn’t my parents’ fault or anyone else’s fault, it was just bad circumstances. I had a bad juvenile form of arthritis. I would sit with my synthesizer in my mom’s sewing room, which I converted into my dude space, with my Morrissey poster and all that stuff. I’m so proud that I allowed myself to be the weird kid. Even supposed hip kids, when I was in high school, still felt like they congealed into these weird groups: punks or hardcore kids or rave kids, and I was like, “I like all of that stuff, and I like Def Leppard too.” Loneliness, when you’re 15…

SYMONDS: I just feel like it’s misplaced boredom, a lot of the time.

SHOWALTER: Yeah!

SYMONDS: And there’s something kind of delicious about that, being allowed to be bored. As an adult, if I’m bored, I feel guilty because I should be cleaning my apartment, I should have filed my taxes.

SHOWALTER: Exactly.

SYMONDS: All of this responsibility gets in the way of boredom, and boredom can be really fruitful when you’re a kid.

SHOWALTER: Yeah. I was a grocery bagger. I’d bag groceries, smoke cigarettes, and try and Robo-trip when I got home.

SYMONDS: I don’t know what a Robo-trip is.

SHOWALTER: It’s drinking a bottle of Robitussin and getting really loaded. I don’t think you can anymore, because Robitussin has changed. But there was something beautiful about that! And now, yeah, it’s something fucking scary to think about. I am lonely, I’m so fucking lonely, most of my life, and I’m surrounded by people, and I have lots of things to do. When you meet an amazing person or have a great talk, this sun kind of peeks through, and you’re like, “Oh, that’s what it means to not feel that.” It’s not sadness anymore—loneliness is much more severe than sadness.

SYMONDS: Yeah, it’s something more like desperation.

SHOWALTER: Yeah, you can grab onto sadness, because it seems to be placed by events. “I’m sad because my grandma’s sick, and I don’t know how to deal with it, and I’m trying to figure that out.”

SYMONDS: Like if there’s a causal relationship, it’s still in your control somehow.

SHOWALTER: But loneliness is like, “I am empty; there is nothing fueling this fire anymore.” I have an ability, though, to function through tragedy. I had a house burn down and I went to school the next day. I smelled like ash, still. So I have this self-survival mechanism, but that’s almost just as unhealthy, because I don’t allow myself to deal with it. Ever.

SYMONDS: I think that’s probably where your record came from, though!

SHOWALTER: Yes! I’m so happy that it happened, because I don’t think I would have lived. I was actively trying to just destroy myself. I hate to make myself seem like there is anything more special about this record than anybody’s record they write—but honestly, I listen to a lot of records and I’m like, “This is bullshit. I’m not feeling.” Dean Ween said, “If you’re going to miss, miss big.” That’s what I want to do with this. I might have missed completely, but I wanted to do it big.

Smashing Pumpkins, that guy went for it. If you hate it or if you love it, he went for it every time. Rush went for it. Led Zeppelin went for it. And those are my heroes. My hero’s not the fucking taste-of-the-month Ivy League band that met in Poli Sci or whatever. Some of them make amazing music, I love some of their music. But a lot of the time I’m like, there’s no substance to this, there’s no thrill; it’s like watching two of the most boring, beautiful models have sex. I want to see passion. I’ll be the first to admit, I’ll listen to some of my old records, and I’ll be like, “You’re painting in a very dull brown.” I feel like this one is the first colorful sounding record, because there are joyous parts and there are disastrously bad parts.

SYMONDS: I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the difference between not being immediately hopeful and not even believing in a future hope. Even as the record reaches some pretty dark, rough spots, there’s never the sense that you’ve stopped believing that sometime in the future there might be hope again. Especially on “Woke Up to the Light,” which is my favorite song on the album.

SHOWALTER: Yeah, that it might come back. And even as self-destructive as my mind is—I dream about suicide, I don’t want to, it’s just happened since I was little—there’s some internal motor that not allowing me to give up life. Hope isn’t a concept that I think about a lot. It’s never anything as soft as hope; it’s like, “I will not succumb, I will not let whatever bad stuff is happening to me win, I will not let people that are hurting me win.” It’s weird, there are more comfortable moments where it’s like, “I’m thinking about hope and what’s going to come,” but in the desperate times, it’s almost like a time of mental war—that’s a luxury I can’t afford right now. I have to think about how am I going to get the dishes done, and how am I going to get this day started. That’s what I have to do often. It’s funny how a lot of my records have actually been written in times of utter calm in my life, and they are reflecting on pain. This is the first time where it was right when it was happening. The pot was being stirred.

SYMONDS: You seem to think of your songs, once you’ve gotten them out, as entities that exist separate from you, and you almost have a sense of duty to them.

SHOWALTER: Yeah, they’re not mine anymore. I was lucky enough to be able to tap into whatever ether allows me to write those songs, and then I need to honor that. I’m able to translate my feelings to music; other people probably could do it through a therapist or just talking to people. I can’t do that. Even now, we talk and I’m still nervous about this interview; I’m good at relating my thoughts, but then there’s this extra layer down here that I don’t even know about. It’s not that I don’t want to share it with you, if I could I would, but I don’t even know how to get there. I feel it bubble up sometimes, and sometimes the songs tap into that. At one point I say, on one of the songs, “I was in love, but it was changing.” I have no idea what that means, but it scares the shit out of me every time I hear it.

SYMONDS: [laughs] It just came into your head and there it was?

SHOWALTER: Yeah. I could have written an academic paper on how I wrote lyrics on previous records. No idea how [on this one]. And there’s lyrics where I’m like, “Why did you rhyme fears and tears? What are you doing, Tim?!” Two records ago, I would have never, ever let myself do that, but this one, I was like, “I don’t give a fuck, this is how it comes out.” I don’t care if some of this stuff is repetitive or I’m quoting other people’s lyrics in it.

SYMONDS: This album sounds more mature the other three—but not in a way that I could have predicted based on listening to music you made at 24 years old. And that’s something you can probably extend to a process of growing up in general, that you can never predict how it will happen until it’s already happened. The kid in “Goshen ’97,” did he have specific ambitions? How are you different from how he would have thought about you?

SHOWALTER: I actually would have been about 75 pounds lighter, 10 pounds of hair lighter, and with really kind eyes that hadn’t aged with the pain of life. But I think he would be really psyched! All I wanted to do was not be in Goshen, not be who I was, not be in my circumstances; get to dress however I want to dress, get drunk, get tattoos. Even though there were really hard times, if I would have still been a schoolteacher at 32, I think 15-year-old me would have been really bummed: “Dude, what are you doing? Your dad worked a job for 35 years that he hated more than life itself; don’t do that.” This really is the first time in my life where I achieved something that, maybe, that 15-year-old would have been proud of. I think I made a record I think I would have liked at 15.

SYMONDS: In your mom’s sewing room, with your Morrissey poster.

SHOWALTER: There’s a parental advisory, because I say fuck a few times; I would have snuck it in, and I would have put it on, and maybe I would have liked it.

SYMONDS: That’s wonderful. We’ve been having this very weirdly lighthearted conversation about depression and loneliness and feeling fucked up…

SHOWALTER: And why not!

SYMONDS: But you don’t seem, right now, to be in a terrible state of despair, and I hope you’re not.

SHOWALTER: I hope I’m not. I hope I’m not really good at masking it. I think it’s okay. It arrives sometimes without me knowing it, but I’m just excited to be productive. I almost died Christmas day. I got in a car accident. My car got hit by two semis, and it’s totally dramatic, but I remember thinking, “I made Heal. I’m good.”

HEAL IS OUT NOW. FOR MORE ON STRAND OF OAKS, PLEASE VISIT THE ARTIST’S WEBSITE.