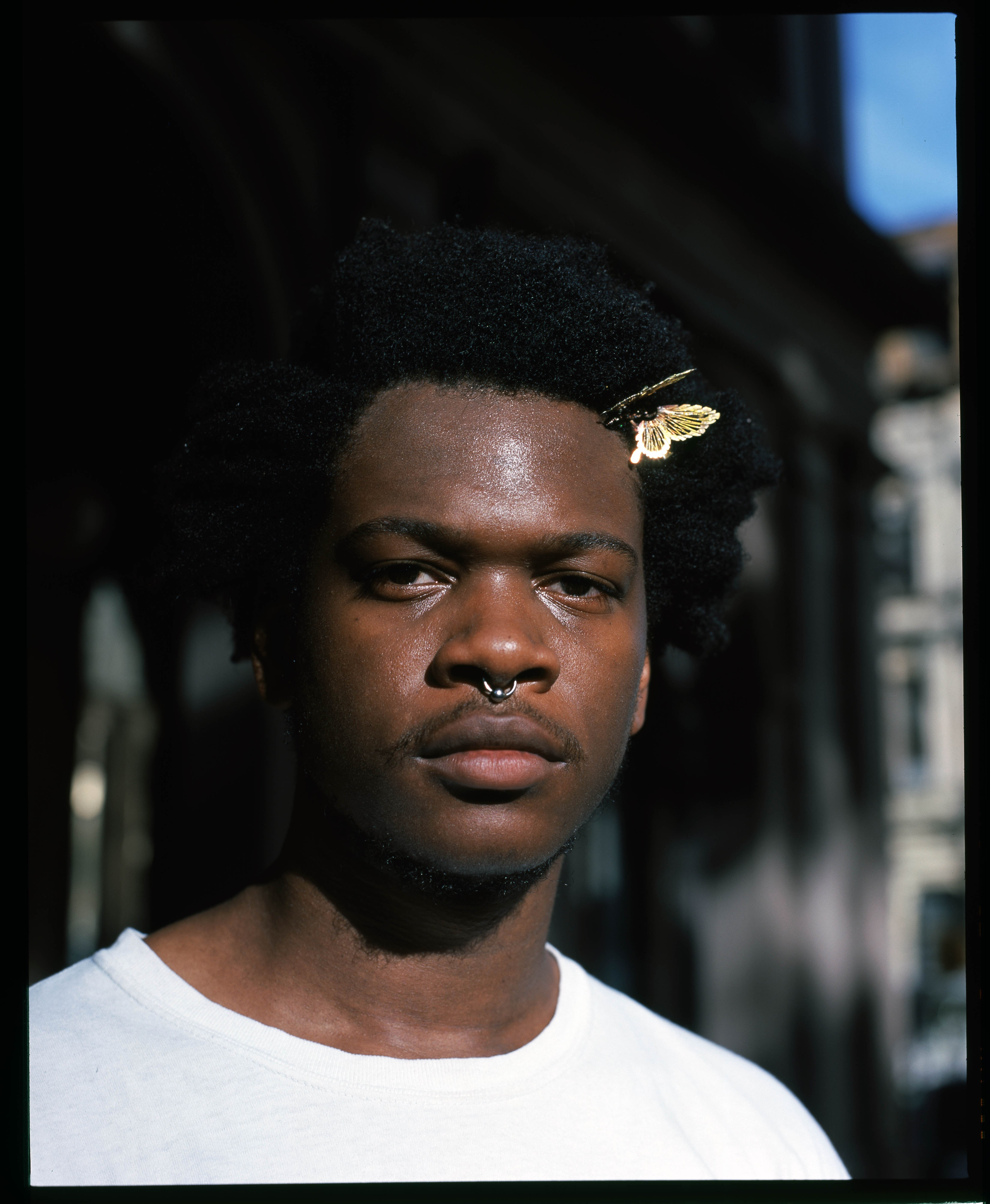

Pop singer Shamir tackles mental health on his new record

Shamir Bailey almost quit music six months ago. In 2015, at the age of 19, he released his breakout experimental electronic pop debut Ratchet; it transformed the Las Vegas native into what he now calls an “accidental popstar.” When it came time for the follow-up, however, Bailey wanted to try something with less slick production, and more emphasis on his voice and instrumental skills. He recorded and scrapped two full albums, and was subsequently dropped from his label, XL Recordings. Fed up with the music business and the creative expectations thrust upon him therein, Bailey made the impulsive decision to record and master his second record, Hope, in one weekend in his bedroom. He posted it on SoundCloud for free in April of this year. “I really thought that I was just going to quit and that Hope would be my last goodbye,” Shamir told Interview, chatting on a Soho stoop on a particularly warm fall day. “I was on a limb, and it was kind of just like, I’m going to give you the last of me, and then just leave it at that. I didn’t think that people would actually gravitate to it.”

Shortly after the release of Hope, Bailey experienced a psychotic episode and spent five days in a psychiatric hospital. He was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, and returned home to Las Vegas. Boredom motivated the singer to write new material about his challenging year, some of which would turn into his third record, Revelations. It’s out Nov. 3 via family-run indie record label Father/Daughter Records. Over ‘90s grunge-influenced grooves, Bailey addresses his mental health issues head-on in his gorgeous falsetto. “Float,” for example, was written about one of Bailey’s hallucinations during his psychosis. “It was kind of like my imagery of what heaven would be like, because at certain points I literally thought that I was dead,” he recalled. “When you’re that detached from reality, it’s like, am I dead? Is this the afterworld?”

Shamir believes in signs; he writes monthly horoscopes with his mother for Talkhouse, and finds meaning in numerical symmetry.“[Revelations] comes out November 3, it’s my third record, and it comes out right before my 23rd birthday. Three is this year’s number for me.” With dark times behind him and fate on his side, the sky is the limit for this talented young crooner.

NATALIA BARR: What was going through your mind as you pressed the button to upload Hope on Soundcloud?

SHAMIR BAILEY: I never had so much anxiety in my life before I, yeah, pressed the “Upload” button. It was crazy, because I was like, I can’t believe this actually worked out, I can’t believe that I even got it mastered. Everything just flowed and felt very meant to be, but also, I didn’t tell my managers at the time. I didn’t tell anyone. I just did it. It was very nerve-wracking, but I was very happy with the response. It made me happy to see that people do react to vulnerability.

BARR: With the introduction of Hope, you said you were almost going to quit music the weekend you released it. What kept you from quitting?

BAILEY: I think the good response from Hope, that kind of gave me a reassurance that I can do this on my own. After Hope, I ended up having a mental breakdown, and having a psychotic episode, and spent some time in the psych ward. When I got out, I went back to being a soul singer, and that’s where Revelations came from, once I realized I had a group of songs together, because I had nothing else to do in Vegas. I was just recording and writing my own album. I’m just going with the flow now. It’s not really that calculated anymore. I’m bearing my soul in these songs, and just giving it how it is.

BARR: You wrote on SoundCloud, “When I would listen to immaculate recordings with my friends, their praise over the quality of the art as opposed to the art itself made me feel really sad for music as a medium in general.” How did that view affect your music?

BAILEY: I think people right now, when they hear stuff like Hope and Revelations, they’re like, “Oh, Shamir is just like anti-studio, anti- clean recordings, anti- nicely produced stuff,” and I’m not. I want to do it; it’s just that it never shows itself to work out in this time period. My goal with these records was to show people that it’s the art itself first. It’s the actual songs first. A friend of mine described it like this, like songs as water. You want water to be as pure as possible. You don’t want your water to be contaminated. Production is like a soda machine, those new soda machines where they have the sparkling water and they add the flavor. That’s what production is. It should add flavor. It shouldn’t contaminate the water. It’s crazy to hear a lot of songs on the radio these days, and even on some of my older songs, you can’t even sit down and play the songs acoustically if you wanted to, because production is what’s driving the song. I think the songs should be driving the production.

BARR: Was Ratchet authentic to you as a musician?

BAILEY: I don’t think Ratchet as far as production and sound was authentic to me as a musician. It was more of an experiment for me that kind of became a life of its own. I went with it, and I was really young, and I was scared to raise my voice a little bit more. That’s my fault, it’s no one else’s fault. I understand the whole XL dropping me because of that. Honestly, I would probably be a lot more miserable now if I was stuck in a contract. I feel like everything worked out for the best.

BARR: Ratchet got such a great response. How does that feel for you now when you have to assert that you’re not making that kind of music anymore?

BAILEY: I don’t resent Ratchet. It gave me a career. It started my career. It’s definitely hard when you know that it wasn’t 100 percent you in a way. Ratchet right now feels like a gateway to me. I think it showed people that I had the skill, but not where I necessarily like to put my skill towards. It kind of feels like a whole other artist.

BARR: How are your musical and production-related visions translating now that you’re signed to Father/Daughter?

BAILEY: They’re just amazing. It’s family. Jessi [Frick], who runs it, she’s so open to everything. It feels great to have this backing, but also be able to do whatever you want. They one thousand percent trust my artistic vision and everything that I want to do, and they trust that I would never steer them wrong.

BARR: Why is the record called Revelations?

BAILEY: As I was writing it and after I got out of the hospital, I was opened to so much about the world around me, about the people around me, about myself, about my own mental health. Being diagnosed with bipolar disorder, and even before I was hospitalized, I kind of had a feeling that there was something funky, and expressing that to other people, but people kind of being like, no, you’re overreacting, it really clarified that for me. There have been so many times where I put my own opinions aside whether it be the music that I did beforehand, to other decisions that people had told me to do, to even things about myself. Now, after everything that has happened this year with my music and also my personal life, it’s been a huge revelation that I just need to do what’s good for me and follow my gut and not worry about the rest. Since then, everything has been pretty golden.

BARR: How similar will it be to Hope?

BAILEY: I feel like it’s definitely a sister record to Hope. They’re both so straightforward and simple. I wanted them to exist in a world together. That’s why I wanted to do two releases this year. I think how close they were made and the short time that happened in between when they were made, it really feels like an answer record to Hope. First comes hope, and then when you have hope, a bunch of revelations come about.

BARR: On “90’s Kids,” you sing about pressure of parents on college kids. Have you ever felt that pressure from your parents about music or outside of music?

BAILEY: No, I’m actually really blessed. I wouldn’t even have a music career or be here. After I graduated high school, I was like, “I need to be an adult now.” I was working, and my mom was like, “Look, you should just take a break here and work on your music.” I was just experimenting and writing these electronic pop songs, literally just to keep my mom happy and stay in her house. That’s a rare case for people my age. I see the pressure with a lot of my friends. I wrote this song with my best friend since eighth grade. It was a little bit after Hope came out. We were on our way to New York, and while we were on the bus, I had the opening line pop into my head: [sings] We talk with vocal fry, we watch our futures die.. I thought that was so funny, because, like, it’s us. [laughs] The college part she wrote, and it was very specific to her, because she’s in college and she knows the stress.

BARR: That song is such a message of solidarity among such a specific age group that isn’t written about all too often. What other messages will you relay on Revelations?

BAILEY: A lot on the record is personal, and that’s why I wanted to release “90s Kids” as the first track, because it’s definitely the more universal message. There is my second single, “Straight Boy.” That song I think a lot of people will relate to. It’s a song pretty much about how straight boys aren’t that reliable, whether it be emotionally, physically, when you need them to be there. They’re just kind of oblivious, living in their own world. The video touches on whitewashing and gay baiting too, and how straight boys are even given credit for being queer these days. I see headlines about Harry Styles as a queer icon, and I’m like, “Where? Just because he wore a pink blouse?”

BARR: In your old interviews with Rookie around the release of Ratchet, you spoke a lot about believing in fate. Did fate come up again with Revelations?

BAILEY: This whole year has been fate for me. When I turned 22 last year, Trump had just gotten elected. Like, happy birthday to me. I couldn’t even celebrate my birthday, and on top of that my phone was broken, and then a bunch of hard times with the music, and friends, and having a freaking psychotic episode, [laughs] and having to spend time in the psych ward, and having to go back to Vegas and die of boredom and heatstroke. But I felt like all of this had to happen for a reason. It’s definitely opened my eyes to a bunch of things, and I think it’s all made me a better person. It’s definitely made me a stronger person, and it’s given me a lot to say for my career and for music and for me to share my experiences. Now, I’m donating a dollar from every proceeds of the preorders of Revelations to Mental Health Society of Pennsylvania. Now I’m very outspoken about mental health, because, having been in psychosis, you are completely detached from reality. That’s so scary. After it happened to me, and especially being in the psych ward and realizing this is not a rare thing, I was like, I have to speak up about this. It’s been amazing, even talking about it in the New York Times. I have people coming up to me saying, “Thank you so much for talking about it. When it happened to me, I was so scared and embarrassed.” Even though it’s something bad that’s happened to me, me being able to put it into art and express it on my platform and have other people relate to it and not feel alone, it’s a positive out of that negative. And again, it all comes back to fate.

REVELATIONS COMES OUT NOVEMBER 3 ON FATHER/DAUGHTER RECORDS.