The Genesis of Rone

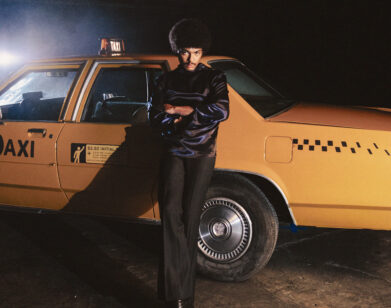

ABOVE: RONE. IMAGE COURTESY OF TIMOTHY SACCENTI

Following up Spanish Breakfast, Rone’s much-lauded debut on InFiné, hasn’t been easy for the Erwin Castex. Forced to contend with high expectations from across the electronic music world, Castex labored over his next release for years, as he expanded his sound and gained inspiration while recording in Berlin. Beholden to neither the music of his native France, nor the minimal tradition of his adopted home, Tohu Bohu is grand in scale, yet delicately intimate: “The concept is, there is no concept,” says Castex.

The title of Rone’s sophomore album comes from, quite literally, nothing at all. Tohu Bohu is the word used in the book of Genesis to describe the swirling abyss that existed before God created light—what in English might be referred to as “hurlyburly.” Like its namesake, Tohu Bohu is a mercurial, vast, and often mesmerizing collection of tracks, ranging from lush techno to expansive pop reminiscent of M83.

We caught up with Rone via Skype, where he talked animatedly about the difficulty of following up his debut, the connection between music and imagery, and the difference between Paris and Berlin.

NATHAN REESE: It’s been three years since your last LP. Can you tell me about your new record, and the process behind creating it?

ERWAN CASTEX: Yes, well, it wasn’t so easy to do this album. For the first one, I just made some tracks—I didn’t realize I was making an album. This second album was different for me. It was like a job. It was a little bit new to make music this way… I was a little bit stressed because I was aware that people were waiting for my work, and for a while it was impossible for me to make music. Finally, I understood it was important for me to forget everything and make music like I did at the very beginning when I was alone in my room. In that way, I could make the album.

REESE: Did you approach Tohu Bohu track by track, or did you have a concept for the LP as a whole?

CASTEX: I mean, it was better if I wasn’t thinking about what I was doing. I was trained to do something more instinctive—something very direct between me and the music. In the morning I would go into the studio, turn on the machines, and forget about everything else. For example, “Icare” seems strange at the beginning—there was something almost ridiculous about it. I’d have to say [to myself], “It’s not a problem. I have to do this,” and then go in that direction.

REESE: There are a lot of beautiful visual accompaniments your music. How do the videos and art play into the record?

CASTEX: In the past, I worked in the cinema industry. It was my main job, and music was just for fun, so I think I have a unique attachment with cinema. When I make music, there is always something from this past—from pictures. There is something that’s a little bit narrative. It’s as if my tracks are little stories. [The visuals for the album] were done by a good friend of mine, Vladimir Mavounia-Kouka. I make the music, and at the same time Vladimir would make the drawings. At the end, we mixed our work together, and there is a kind of alchemy.

REESE: How did you hook up with High Priest of Antipop Consortium to make “Let’s Go,” and what was it like mixing in hip-hop with your sound?

CASTEX: I was talking with High Priest, and it was a very nice meeting. I sent him my music via email and he was very enthusiastic. We worked at a distance, like ping-pong. I met him [in real life] only one week ago—it was very cool. It was funny. It was like he was an old friend. I’m very interested in working with a lot of different people from different universes. When I was a teenager, I was listening to a lot of hip-hop. It was like a dream to make this track. Maybe I’ll try it again later.

REESE: How did writing the record in Berlin change your perspective?

CASTEX: It’s funny, because I don’t think the album sounds at all like Berlin electronic music. But for me, it’s really my German album. If I made the album in Paris, or in another city, it would be a completely different record. It wasn’t influenced by the music, but by the city. There is more space, it’s more quiet—totally different from Paris. Paris is more stressful. I think all these elements give color to the record.

REESE: What other music were you listening to when recorded the album?

CASTEX: For a long time—three months in the studio—I wasn’t listening to anything at all. I tried to isolate myself from the rest of the world. When I’m not working on music, I listen to music all the time, even when I don’t want to: getting a drink with friends, when I’m on the Internet… So there are certain influences indirectly. The thing to do is try to forget everything and make a work of introspection.

REESE: Are there differences between playing to an audience in Paris versus one in Berlin?

CASTEX: There are some differences. In Paris, for example, in clubs and at concerts people are a little bit more aggressive. You can feel that they had a big week of work, and it’s the weekend they have to be like, “Aaaahhhh!” [waves hands]. In Berlin the parties are longer—a club like Berghain opens Friday and closes Monday. People are more relaxed, even if the music is really strong.

REESE: What do you want to make your audience feel at a live show?

CASTEX: Playing live is very intense. It’s a big contrast to the time in the studio. You’re with a lot of people and there is so much energy. People give me energy and I give energy to people, it’s like a collaboration. My music is different when there are a lot of people in front of me. Something special happens. It’s a very curious moment. It’s like I’m remixing myself, because I play my track, but every time I try to play it in a new way. It’s important to me for people to think that there is something special happening there that night, and if there are accidents, I think it’s more interesting.

TOHU BOHU IS OUT NOW VIA INFINÉ. FOR MORE ON THE ARTIST, VISIT HIS WEBSITE.