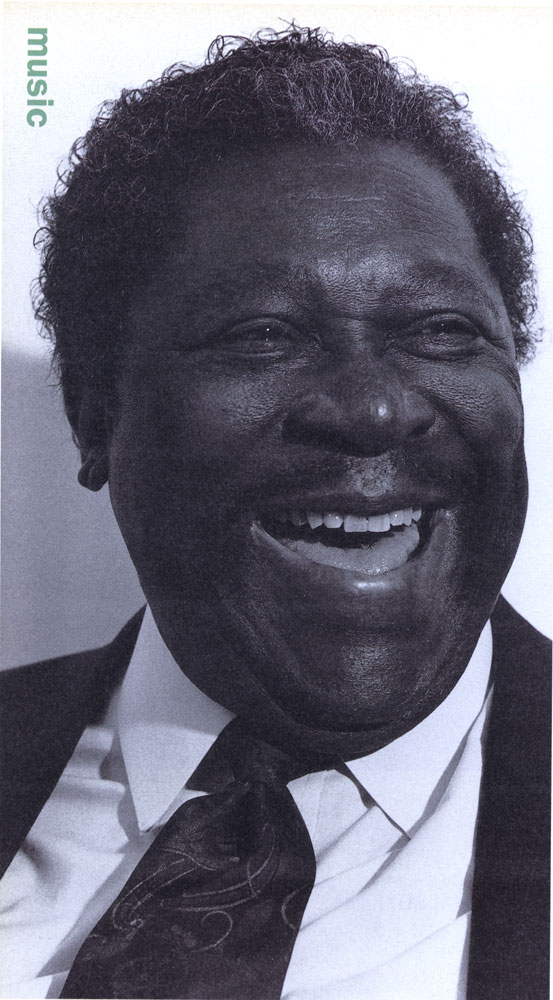

Remembering B. B. King

B. B. King, the godfather of blues as we know it, died yesterday at age 89 in Las Vegas. King’s live performances were renowned for his visible emotion and powerful adaptations of recorded songs. He often looked as though the audience was absent, contorting his face during moments of pure musical ecstasy, allowing himself to focus solely on his craft. His records are just as poignant, remembered for a soulful voice that ebbed and flowed in tune with the striking vibrato of his guitar. Never tiring, B. B. (which stands for Blues Boy) King, played 342 shows in 1956, and between 200 and 300 shows every year around the world for the following half-century. In honor of the blues legend, here we revisit an interview with King from our March 1991 issue.

r&bb

By Dimitri Ehrlich

B. B. King is widely recognized as the greatest living blues guitarist. This title derives not only from his mastery of the guitar but from the generosity of spirit he brings to the blues. Last November, in the midst of a world tour, he shred the stage at the Apollo Theater with Ray Charles and brought the audience to its feet in a bear glossolalia of bluesy ecstasy. Living Colour’s guitarist, Vernon Reid, is among the producers of King’s new album for MCA, and last month, after perofmring at Mardi Gras in New Orleans, King embarked on a three-month tour of the U.S.

INTERVIEW: What was it like when, at 18, you moved from the countryside to the relatively urban Indianola, Mississippi?

B. B. KING: You didn’t have to go to bed with the chickens in the evening. Usually, when the sun went down, you could go to one of the cafes or clubs, which was something I was crazy about. These were things we didn’t have in the country. There was music, electric lights…

INTERVIEW: What kind of music were you first exposed to?

KING: Most of the black people were singing blues, most of the white people sang country, but all sang gospel. And jazz was coming in. Later on we started hearing about rumbas and congas and various fads.

INTERVIEW: You’ve said that your mother thought that the blues was the Devil’s music. Do you ever have second thoughts about devoting your life to a music your parents forbade you to play?

KING: No. Many people who came from the old country—my parents or your parents—meant well. The Ford they had was great, but now we have limousines. I didn’t want to disrespect my parents, so I never played blues around the house. But I knew then, same as I know today, that I wasn’t doing anything wrong. I think that before they died they both felt very proud of me.

INTERVIEW: You spent two decades playing juke joints in ghettos all across the country, and now you’re headlining in upscale venues worldwide. How has this changed your experience of performing?

KING: I feel the same way about that as I do about plowing in Mississippi and moving to Indianola. I’ve learned something. You wouldn’t have wanted an interview with me back then! [laughs]

INTERVIEW: White blues-rock guitarists like Clapton and Stevie Ray Vaughan have copied the way you play and the way Muddy Waters and Robert Johnson played. Isn’t it ironic that these rock guitarists were later responsible for reintroducing you to a larger audience?

KING: Better late than never. If they had not spoken out about who influenced them, then nobody would know that these rock ‘n’ roll people did listen to us. Of course, if Muddy Waters and many of us had been able to be exposed like the rock stars are, then you would have known about us anyway.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE MARCH 1991 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

For more from the Interview archives, click here.