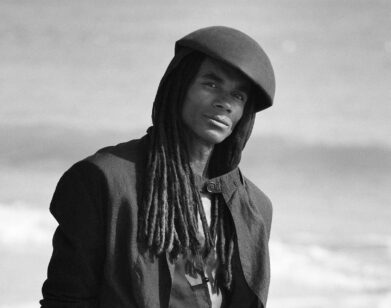

New Again: Robert Plant

Between tours with Led Zeppelin and after recovering from an accident in, Robert Plant dreamt of visiting Kashmir and the Atlas Mountains on the northern coast of Africa. Ten years ago, he came quite close to making this dream a reality.

While it may not have been India or Africa’s most northern coast, Plant traveled to Essakane in the North of Mali—south of the Atlas Mountains—to play at the Festival au Desert. His performance with Strange Sensation’s Justin Adams was captured through the French documentary Le Festival au Désert, but, as of this week, we are all able to watch his experience firsthand. In a mini YouTube series entitled Zirka, Plant is releasing personal footage over the course of eight episodes. His adventure takes him across Mali, from cities where he witnesses dancing spilling onto darkened streets to the expansive countryside and desert.

Before Plant could even conceive of playing with anyone other than Led Zeppelin, Mark Ginsburg spoke with him in our July 1977 issue.

Robert Plant: Led Zepp’s Lead Zinger

By Mark Ginsburg

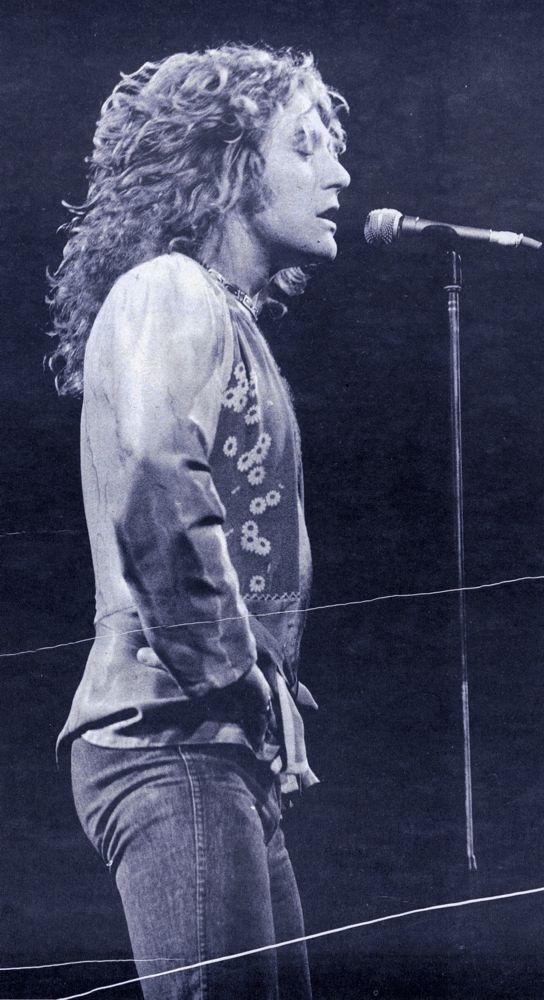

An interview with Robert Plant is rare. But then the same is true for Jimmy Page, John Paul Jones, and John “Bonzo” Bonham. These four men constitute the band Led Zeppelin. Their current North American tour has sold more tickets faster than any other bands that have booked in the same stadiums, concert halls, and coliseums. The newspapers could fold tomorrow and million tickets would sell anyway. A growing number of intensely loyal fans (traditionally not including the press), know that Led Zeppelin’s music has nothing to do with the way they think… only how they feel.

An audience with the Pope would have been easier to gain… but not nearly as much fun in the end. Besides, he probably doesn’t sing as well. Now that Robert Plant’s leg has headled from a gueling auto accident in Rhodes, he leads his private life the way he wants to. And his public life seems equally satisfactory: with the wave of a hand and a “Please,” I saw him silence 20,000 screaming people. With his clap, they clapped. Robert Plant is their own, and his own, “stairway to heaven.”

[April. Late afternoon. On a double bed in Swingo’s Celebrity Hotel, Cleveland, Ohio.]

ROBERT PLANT: [gazing out of the window at a parking lot] Oooh! Is that a Mark V? That is one isn’t it? It’s very nice, I like that. Can you get those in New York? [Shouting to a man with a camera on the street] It’s not worth the pictures! It’s not worth the pictures—forget it!

VOICE: [from the street] You think so?

PLANT: [laughing] Nah—

VOICE: Then I’ll get some tonight at your show.

PLANT: Never heard of it. I’m not going.

VOICE: No?

PLANT: I hear they suck. [to me] So what is your story then, Sir? Or in fact—

MARK GINSBURG: I want to know what yours is…

PLANT: I have no story. My story goes from day to day.

GINSBURG: Okay. What’s today’s?

[silence]

JENINE SAFER: [publicist] Seven Up is great for hair management!

PLANT: Mmm. Well, I just found out that Seven Up left in the hair for 12 hours is the greatest hair conditioner. I mean all this shit on the TV that you see—I don’t believe it at all.

SAFER: But it has to be applied properly by John Bonham [alias Bonzo, Led Zeppelin’s drummer].

PLANT: Where are you going to be?

SAFER: I’ll have to get a schedule off you. Then sit down with Jonsey [John Paul Jones] as well because we’ve got to do the plan. [mumbles]… got to do the plan.

GINSBURG: What’s the plan?

PLANT: Well… discretion is the better part of valor. How to let the family have a wonderful time without knowing it’s all programmed. I might as well tell you that there’s not a lot of towns that I can go to and take family—too many incongruous knocks on doors—”Hello, honey. Have you missed me?”

GINSBURG: So where do you go then?

SAFER: Not Dallas!

PLANT: North Bend, Indiana is rather scenic in August.

GINSBURG: North Bend, Indiana?

PLANT: Ah, well you see I know a lot about the colonies.

GINSBURG: Who colonized them?

PLANT: ‘Twas us! We Redcoats.

SAFER: [after a pause] Last night was so much fun.

PLANT: My jaw’s hurting from just giggling. Now that’s a good sign young man after nine years of rock-‘n’-roll. That you can still laugh at each other for about eight hours ’till you have to go to bed holding your head.

SAFER: [leaving room to re-sew the spider-web design on Plant’s concert shirt] Same time next week—

PLANT: Well, it’s going to be the big one tonight. Now, did you come to another town? I was supposed to see you in Chicago, right? What happened?

GINSBURG: Do you really want to be reminded?

PLANT: Yeah.

GINSBURG: You had a strange afternoon…

PLANT: [screams] Ohhhh! There was nothing strange about tit. It was regular, but…

GINSBURG: Typical strange afternoon, then. It all depends on your point of view—

PLANT: …which angle you lie.

GINSBURG: Right. Well then, what would you like to lie about?

PLANT: No! I was meaning “lie” as in what I’m doing now—lying down.

GINSBURG: And get high?

PLANT: No. I made a vow after two years of not working, because of the accident, that I should, uh, take care of my health 100 percent. With two years of living not quite sure whether you’re going to rock-‘n’-roll again, the build-up to this tour was tremendous. The inspiration was flowing, ’cause when I knew that I could go back onstage again with my foot, I just said, “Right. Now, if I am going to do that, if I’m going to dance again, perform again, then I’m going to sing better than I’ve ever sung before. There’s nothing that’s gonna stop me.”

GINSBURG: You would not have settled for remaining in the studio rather than onstage?

PLANT: Oh, no. When I started all I wanted to do was get out in form. I just wanted to sing. A simple thing. I loved the feeling of letting fly, of pushing as far as I could go with my voice. The only way you can really graduate how you do it is by doing it regularly to people who don’t have to be super impressed. You can do it in the studio all day long but you don’t get the flashback that you get onstage.

GINSBURG: Do you still get the flashback as much each time?

PLANT: More now. Much more now, this tour.

GINSBURG: You realized you’d miss it then.

PLANT: Oh, essentially there’s a very serious aspect underneath everything now for me. Well, not serious but one of relief, I guess. There is nothing that will stand in the way of the fact that I’m going to put out 199 percent every night. So, I’ll leave the pot alone for a bit, ’cause it only clogs up my vocal cords, anyway. You get tar up them. [demonstrates hoarse sounds]

GINSBURG: Any favorite Zeppelin albums?

PLANT: I don’t have any favorites. Each album comes from definitely a different period in the evolution of each of us individually as creators and the role that we take in life. The external stimuli changed… so the songs are full of lots of different meanings. Each album has a different atmosphere. The third album and Houses of the Holy seem to be the two albums that people didn’t get off on quite as strongly as the other ones. But I think they contain the basic ingredients for the further pursuance of what we’re doing… the turning point to relieve the tedium of repetition.

GINSBURG: Presence seems to be a turning point, too.

PLANT: Presence was our phoenix.

GINSBURG: Yours mostly?

PLANT: Well, I know I’m talking so it’s coming from me, but when you sit in a wheelchair and sing the whole album, the very fact that you’ve sung it is fantastic. But for everyone, in that we got it together in such a short space of time under such odds not knowing what the outcome was going to be—not of the album but of the future of the band.

GINSBURG: Why not knowing?

PLANT: Because the doctors could never really quite tell me, all that time, about how inactive I might have been left from the accident. So we were just kicking it from the very depths of our determination.

GINSBURG: Could you have stayed on top without performing live?

PLANT: Oh, I don’t think anybody would have want to. I guess we could have made it cutting studio albums, but it takes shows and tours for, uh—

GINSBURG: Energy?

PLANT: Yes, and inspiration! Events like last night. Silly times, and….

GINSBURG: You used to sing on rather simply about a girl—always one that you couldn’t have but wanted badly, for instance. Now the description is more colored, complex.

PLANT: Sure. Well, I’ve tried to do that on things. Like with Celebration Day, going back: “Her face is cracked from smiling” and that sort of thing. The impression of a free world all the way through. It could still have been greyed but it could have also had that natural effect that time gives it.

GINSBURG: But everything you sang about early on—the open spaces, the beautiful women, the dreams—aren’t these all things you’ve now had—goals you’ve reached?

PLANT: I’ve touched, that’s all. You have nothing. One should never allow themselves to think that they have, one can just touch—to have is to lack appreciation, to touch is to want to touch again.

GINSBURG: So some things are still inaccessible to you now?

PLANT: Definitely. I’d like to think that’s the way it should be. That’s what keeps me going on and on and on. Like that bit in our movie, [The Song Remains the Same], the princess thing. Everybody thought I was out to… well, “There’s Plant after another chick…” But there, the whole thing is that in the end the chick disappears before my eyes. You must just get in reach so that you know you’ve made the effect—the primary effect. And you mustn’t grab it too hard… so the most basic things can still remain a pleasure.

GINSBURG: Ten years ago did you want to become a rock star?

PLANT: Well, I didn’t look at it like that. I just wanted to sing. Nobody ever looks at it like that. Didn’t even know what one was then. Still don’t.

GINSBURG: Well what happened?

PLANT: I’d already played with people who’d got the same amount of adrenaline and drive as I’d got and it just so happened that Jimmy [Page—LZ’s lead guitarist and former member of the infamous Yardbirds] had got more than I’d got. He could channel it. He knew which way to let it go. And that was the best thing that ever happened to me, musically. I’d found someone whose tastes were basically along the same lines. Who’d got the patience to allow me to—it’s like dangling your foot in a swimming pool to see how deep it is or how cold—accustom myself to everything that would come along that he was already aware of from the Yardbirds. Perfect relationship.

GINSBURG: Has it changed much?

PLANT: Yeah, because I’ve grown up. My experiences of course now come up to the same ones as his. I guess we’re both sort of trotting together rather than him showing me the way as he did in the early days.

GINSBURG: Where are your musical roots?

PLANT: In anything that’s done wholeheartedly from Edith Piaf through to Howlin’ Wolf. From anything that comes from that point. Some people say I sing from the groin. In the early days it was Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters, Ray Charles, Drown My Own Tears—stuff that was ultimately sincere. And some wild, wild rock, too: Little Richard, early Presley stuff—before he went into the Army. Presley was definitely a great inspiration to every guy who ever had a hard-on in the whole of the Western world, I should think. He shook everybody well and true, and we just kept on shakin’. But he started it.

GINSBURG: And now, Led Zeppelin is left to carry the ball…

PLANT: I don’t know… I’d like to go to more concerts to see the overall effect of an audience because I like to see excitement. But I like the excitement to be contained. In the early days when we used to play everybody was bangin’ their heads on the stage and going completely crackers. Now they sit down and absorb. There’s a sort of transfixion between ourselves and the audience, which is wonderful. It’s a great level to have reached with people who you don’t know by name. That is my idea of the ultimate sort of communication level.

GINSBURG: How far away do you feel from an audience when there are tens of thousands of people watching you? How can you see or hear?

PLANT: You pick it up without sight or sound. I suppose for a vocalist it’s super built-in because if I talk, I do the talking. I think I can feel better than I can see.

GINSBURG: What music do you listen to at home when you listen to music?

PLANT: Uh, I like Little Feat, Fleetwood Mac—obviously. That little lady ought to come and sing on one of our albums. If she were to come sing on one of our albums—it would…What’s her name?—Stevie…

GINSBURG: Will you or any LZ member play onstage or record with anyone else?

PLANT: Well, no, I think it would only be impromptu. On other albums maybe just guesting for a track—on a very light-hearted level. I can’t see any serious turn one way or another. We just enjoy playing with each other. I wouldn’t like to go and sing with anybody else at all.

GINSBURG: Why not?

PLANT: I just don’t. When you’re singing we all phrase each other in the most remarkable ways. I might hit some sort of thing I’ve never done before—some vocal pattern. Bonzo will pick it up—he’ll phrase with me instantly and then Pagey may join in or start some other phrase—it’s like a quadrant.

GINSBURG: Where did Kashmir come from?

PLANT: The rhythm came from Bonzo. The sort of striding majestic element really came from Jimmy’s and my leanings toward the East. I wrote the lines after driving into the Sahara Desert because I knew that I was on my way to the Spanish Sahara and there was the war on between Morocco and the Spanish. I kept bumping down a dusty desert track—nobody for miles except, occasionally, a guy on a camel, waving his hand in the most nonchalant Arabic way. And I thought, “Well, this is great but one day—Kashmir.” And the sun was beating down upon my face…

GINSBURG: So your ideas spring from place you’ve been or want to go?

PLANT: Well, Kashmir is my last resort. I think, if I truly deserve it one day, I should go there and stay there for quite a while. Or if I really need it at any point, it should be my haven, my Shangri-la.

GINSBURG: Any place else?

PLANT: Well, the whole point of “Achilles’ Last Stand” is that, though the story builds, it’s centered around one spot on the top of the high Atlas Mountains. One tiny little spot on the side of a track 10,000 feet up—looking down over half of Southern Morocco.

GINSBURG: “Achilles’ Last Stand”—I would have thought the title had something to do with your accident.

PLANT: It did. It did because I fell over when I was singing it in the studio and I was rushed to the hospital. They thought that I had fucked it for good. [moves his leg up and down in the air] So I spent two week yet again with it up in the air. I still hadn’t walked—which is after four months without walking and I’d put all my weight on it—went down, bang! Pagey virtually carried me to the hospital. And when it got to a point where I could lower it gain off the bed without touching the ground, I was wheeled to the studio while the others were asleep and did the whole vocal track all over again from start to finish. I said, “Right from the top, I’m going to do it again and I’m going to call it that.”

GINSBURG: What about the song “For Your Life?”

PLANT: That’s a sarcastic dig at one person in particular that I know, who was a really good person but got swallowed up with the whole quagmire of the downhill slide, the L.A. syndrome. You know the sort of thing. “Hung on the balance of a crystal pane through your nose…”

GINSBURG: But you must see so much of that—

PLANT: Yeah, but when it affects people who I love then I sort of snap back at them—”Don’t you understand that you are now immortalized—The parody of it all… is there for you to behold.”

GINSBURG: And why do you think that happens to people?

PLANT: It’s the way… these aren’t people in the immediate surroundings but they’re people who come and go who we know—usually of the opposite sex. People get carried along with the whole momentum and the adrenaline of a rock-‘n’-roll band. We’re in one that’s been going for nine years, ’cause we can still shake it better than anybody else. Then when you leave people behind in a situation you say, “Bye, see ya next time…,” and they sort of slide into the L.A. syndrome, and New York. You come back, and they don’t look as well as they should do, you know, the smile has changed a bit. And this [“For Your Life”] is sort of waving your finger and saying, “Now you watch it.”

GINSBURG: You think they put too much stock in it all?

PLANT: Well, I think it carries them away.

GINSBURG: It wouldn’t carry you away?

PLANT: It carried me away but I carried me away, because we are it, the thing that rolls.

GINSBURG: So then where can you get carried away to now?

PLANT: Well, it’s entirely up to me how far over the top I want to go, you know.

GINSBURG: Have you peaked?

PLANT: I don’t think there is such a thing as peaking. Because if there is so much change, then how does one know when one’s reached the pinpoint?

GINSBURG: How do you measure your success?

PLANT: By my own satisfaction. If I doubt what I’m doing then I’ll go about putting it right—readjusting. Time is too precious to… dance with half-measures.

GINSBURG: You have kids?

PLANT: Yep. A boy and girl and there’s no compensation for children. You can never compare any elation at all to watching a child… because the child is only the reflection of yourself and those of the people who surround it. So really I guess I prefer to be with them. But, you know, when you can’t take this out of your blood…

GINSBURG: What do you do, more or less, when you aren’t singing?

PLANT: [smiles] Wish I was… I don’t know… I have a great love for the more atmospheric parts of Britain. The parts that contain true atmosphere. The days of Albion, the Dark Ages, if you like.

GINSBURG: You must have a more manic side, too.

PLANT: Oh yeah. I’m a total soccer freak. I total soccer freak. Absolute total.

GINSBURG: Will you be able to start up again, at all?

PLANT: I can’t play anymore. I can play touch soccer where I could tap the ball around and do tricks and things like that. But I couldn’t go in, or tap hard. I spend every weekend, every possible moment with the soccer team that I support. Get involved with them, goin’ to see them and having sort of discussions with the management and chairmen how to project a soccer team in the ’70s—on a parallel on how to project rock-‘n’-roll, I guess.

GINSBURG: Any projections for rock ‘n roll?

PLANT: Yeah. Do it good. And do it so nobody’s going to forget it—and that’s what I say to them—play like fuck and people will never stop talkin’ about you.

GINSBURG: We are so stepped in technology. Someone can listen to a studio record, then go to a concert by the same group and expect the music to come out the same.

PLANT: Well, I don’t know whether they do or not. I know that I go about with the voice, which is the hardest thing to sort of play around with and yet the most enjoyable, obviously, because I’m a singer. I have my little machines that I like to play with. I like to make my voice sound like a piece of tin that’s been stuck on the side of a chair, lifted up as far as it would go and then let to spring—”doooiiinng.” I like to make it into a piece of metal from time to time and I can do it, both with the movements in my throat and with, uh, my little toys… So I like to take it beyond just a voice, more into the realms of a weapon.

GINSBURG: A weapon?

PLANT: A sharp spear.

GINSBURG: Do you care at all what the concert critics and writers get printed up in the papers?

PLANT: Not really, because the proof is in the pudding. I mean the people who come are the people who care.

GINSBURG: And the people come!

PLANT: And if they come and I see a smile on their faces, I know that it’s all right.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE JULY 1977 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.