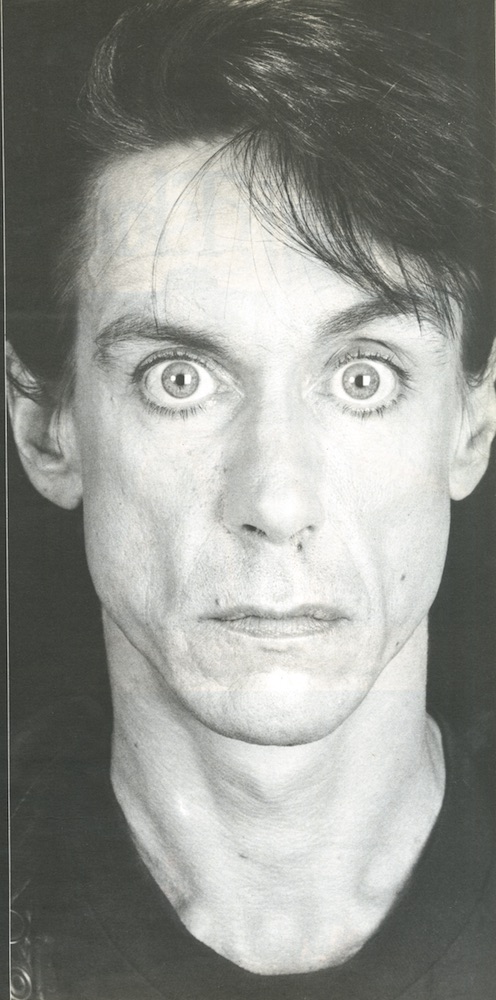

New Again: Iggy Pop

Musical genres and generations came together on Monday night with one voice: to preserve Tibetan culture. The Tibet House hosted its 30th annual benefit concert and gala, spearheaded by Philip Glass and featuring special performances by Canadian up-and-comer Basia Bulat, FKA Twigs, Sharon Jones, the Patti Smith Group (sans Smith), Iggy Pop, and more. Iggy, the last act of the night, performed four songs in total, finishing with a special tribute to David Bowie. Jones, Bulat, et al. returned to the stage (although FKA Twigs was absent) to sing “Together,” which Iggy Pop originally co-wrote for his LP Lust for Life with Bowie. On the stage at Carnegie Hall, though, Iggy Pop performed “Tonight” as a duet with Sharon Jones, much like Bowie later recorded the same song with Tina Turner on his album Tonight. In honor the performance, here we revisit an interview with the icon from November 1986, in which he discusses Bowie and the everlasting life of this exact song.

Iggy Pop

By Lisa Robinson

Iggy Pop, considered by many to be America’s original bad boy/rock ‘n’ roll rebel, has returned to the public eye after a four-year hiatus with a brilliant new album, Blah Blah Blah, and a dramatic role of Martin Scorsese’s movie The Color of Money. The album, his first under a recording deal with A&M Records, also marks a professional reunion between Iggy and his longtime friend and sometime producer and co-writer, David Bowie. This should be the breakout album for the performer who for the past 18 years—from his beginnings with The Stooges in Ann Arbor, Michigan, through countless albums and notorious on-stage performances—has embodied the raw power of rock ‘n’ roll energy. More significantly, it coincides with a new, cleaned-up, married Iggy, who says he can enjoy simple things these days—like being friends with his dentist and shopping in the supermarket.

LISA ROBINSON: What have you been doing for the last four years?

IGGY POP: Well, after Zombie Birdhouse came out, I toured behind it in the fall of 1982, into the spring, and in the summer in the Far East. At that time, I found my work self-referential; it was getting to be rock songs about a rock singer who lived a rock life on the rock road, and I was starting to wonder what I would be like to rent my own apartment, what it would be like to have a checkbook.

ROBINSON: You never had a checkbook?

IGGY POP: No, I never had a checkbook. It used to be cash in hand, stuff in the pocket, or a manager would keep some accounts and give me money. I started to wonder what it must feel like to actually make a profit, pay taxes, and to have a phone listing, and a manager. And also, I was sick of sleeping around every night.

ROBINSON: What do you mean, sleeping around?

IGGY POP: Casual sex.

ROBINSON: You were still doing that?

IGGY POP: Yeah, sure I was. Like a dog.

ROBINSON: Weren’t you afraid of getting a disease?

IGGY POP: You know what I think you get scared of more—especially me, after touring for so long and being in bands for so long—you start to associate certain behavior with the music. It’s like people associate having a cigarette with having a cup of coffee, or lunch. It’s the same thing: I would think, “If I can’t go out and pull some teenager tonight, maybe I’m no good on stage anymore.” And you start to think that you even need it as a motivation. I did, anyway.

ROBINSON: But you’d had a girlfriend, no?

IGGY POP: I’d have a few on and off, but the commitment was always more on the girls’ part than on mine, to be perfectly honest. So, I met a girl in Tokyo, on my Japanese tour, with whom I’ve been living ever since, very happily. Her name is Suchi.

ROBINSON: You’re married now.

IGGY POP: Yes, we did it for the government, because she couldn’t stay otherwise. Neither of us wanted to. We looked at each other suspiciously and said, “I’m gonna marry you?” But we figured, let’s try it, so we went down to City Hall, I think it was October, two years ago, and we were there with all the other immigrants. It was a potpourri of Portuguese, Puerto Ricans… Anyway, I saw a little daylight coming in the summer of ’83. David’s [Bowie] recording of “China Girl” was going up the charts and there would be a little income from that for me as the writer. And my own albums had sold consistently, so there was a little money coming in, and I thought this was a good time to get off the merry-go-round. I didn’t feel in touch with reality.

ROBINSON: Had you been having real problems with drugs and drinking at that time?

IGGY POP: Well, it wasn’t like I was going to run out and score heroin and score an ounce of coke—but incidentally, on the road, I would usually get tanked up and as stoned as I possibly could to go on stage. And offstage, it would be a demon that would come up about twice a week.

ROBINSON: Do you think you’re lucky? You’ve managed to stay alive after years of abuse. You still have this 18-year-old body.

IGGY POP: I don’t think I’m lucky; I think I have a tough constitution. That’s a lot of it. And I’ve been wise enough to listen to other people. I was unconsciously cultivating as many straight friends as I could.

ROBINSON: Where did you meet them?

IGGY POP: [laughs] Well, David has gone quite straight, so that was a good influence. And my wife—my girlfriend at the time—was quite straight. My tour manager, Henry, has always been a dream, and he’s very straight—wife, kids, Catholic Church, all that. And then, after I got off the road, I had a doctor in Los Angeles who helped me over the big emotional hump of cleaning out, and at the same time I hired a business manager for the first time in my life. I stayed in L.A. long enough to get on my feet, and then I moved back to New York. The reason I moved here was that I don’t feel warm outside of a city; it’s too barren in the suburbs, and L.A. is a suburb. Here, it felt active. I wanted to learn a little bit about acting, not because I thought I’d find a star vehicle and set the world on fire, but I thought the discipline of it would be good for me. I met a good coach, and I joined her class—with a lot of hungry young actors who really didn’t acre if I was a rock ‘n’ roll singer or not. I started to learn to get a focus, without having to jump up and down every few seconds.

ROBINSON: What else were you doing? Any writing? Music?

IGGY POP: Yes, in the morning I’d write these essays, anything that I’d feel like writing, and in the afternoon, I’d spend time with my guitar. I had decided after listening to my last four or five albums that my biggest weakness musically was melody. the reason I had been singing in a monotone over the chord patterns in my songs was that I never practiced doing melodies. So I thought that if I practiced doing melodies for a year or so at home, I would learn to think melodically, and when I went to work it would come out, and it did, on this album. What else was important to me…? I spend a lot of time in the grocery store, shopping.

ROBINSON: So you had never done any of those so-called normal things before? Like shop for food?

IGGY POP: Well, I had flirted a bit with that when I was living in Berlin. But the difference was that in Berlin I would stay up for three nights and crash for two days and get up at the end of the week and then shop at the supermarket. And for so long, I had thought if I was going to write a song, or get “into” something, I had to at least smoke a joint or something. And that didn’t work anymore. Once I was fairly well cleaned out, even a little bit of a drug getting into my work threw me off kilter. I’m not the kind of person who could join AA or have rules for myself or on Thursday take this vitamin pill. So, basically, I learned the hard way. I learned by trial and error, and tried to get drugs out of my work. That took about a year. If I was going to work, it was best that I be straight. And I was surprised at what came out. I thought, “Wow, it sounds really stoned anyway.” It sounded good to me. I found out that there was a lot in there. what all this comes down to is I was just trying to get in touch with myself. And I met some interesting people in New York who weren’t in show business. I even got to know my dentist. Then a year ago last summer, I had some money saved up. Me and Suchi had been taking subways and eating at home real cheaply—we were scrimping and putting the money in the bank. I had about $40,000 saved up, took the money, and what I didn’t want to do was get a dinky record contract, the kind they give to broken-down rock stars. I thought I had to finance a new chapter for my music myself.

ROBINSON: Why did you go to David [Bowie] first?

IGGY POP: Well, you see, I’m not a singer, a walking instrument like Aretha Franklin. When you get an Iggy Pop record, you don’t get “Iggy Sings.” I am also a style of music, an approach. And if somebody’s going to produce me, they should be producing my sound for me. And that’s something I have to come up with myself. David and I had talked for a couple of years about him producing my next record, but why should he have to come up with the sound and the songs and the musicians? I wanted to do this myself, and, in fact, he had to nearly twist my arm to let him produce it once I was done with the demos.

ROBINSON: Was Suchi with you the whole time you were recording the demos in L.A.?

IGGY POP: Yes, Suchi was with me the whole time, cooking dinner, helping me. It’s good to have somebody taking care of you.

ROBINSON: You had that great line in one of your songs, “I’ve done my best, now you do the rest.”

IGGY POP: Well, I take care of her, too. So by mid-October of least year I had these finished tapes, and I gave it to a well-connected lawyer in L.A. who I knew, and I started to get bites, and then I thought, “Okay, I need to get this brilliant producer.” I needed one more musical person…I wanted someone to counterpoint what I was doing. I was looking for someone who could color the music. Then David came to New York in November, and he called me up and asked if I would like to come and hear his demo tapes. he was about to record the songs for Labyrinth, and I said sure, and that I would bring my tapes as well. To tell you the truth, the only reason I’d been able to save money and make these tapes was because the income from the cover versions he’d done of my songs had been good; I was really grateful.

ROBINSON: What songs besides “China Girl” had he covered?

IGGY POP: He’d done “Neighborhood Threat” and “Tonight.”

ROBINSON: Did you like his versions of your songs?

IGGY POP: You’re not going to get a straight answer from me on that.

ROBINSON: You certainly couldn’t have liked “Tonight.”

IGGY POP: I thought “China Girl” was the best of them. That was very commercial.

ROBINSON: Well, let me ask you this. Aside from being please to make the money, ego-wise, were you upset that he had the hit with it and you didn’t?

IGGY POP: No. And this is important, because never once, except when I did the song “Bang Bang” with Tommy Boyce on my last Arista album [Party], and never since then until this album, have I ever gone in the studio trying to get a commercial hit. I always went in with a very specific idea of the sound I wanted, and once I’d recorded I’d try and make it sell as much as I could, but I only went in thinking of a sound I wanted. So, it’s no surprise to me that he got the hit and I didn’t. But what I realized was that he did dress it up nicely, and my god, he does sing on key well.

ROBINSON: So you played him the tapes.

IGGY POP: Yes. He was skeptical at first: I think he didn’t want to put the tapes on because he probably thought that I was out in California doing Stooges retreads. And he heard the tapes and his jaw dropped. I was really proud, and proud that he and Coco [Corinne Schwab, Bowie’s personal assistant and longtime companion] really liked them. I was able to show them that I had not been wasting my time, or wasting the money that I’d made off his records.

ROBINSON: Are David and Coco sort of like parents to you in some way?

IGGY POP: There’s an element of that, yeah, sure. Because they’re the only people from show biz I’ve ever met who I actually do enjoy and like and who are involved in the highly organized, professional, slick world. I’ve learned a lot from them about an entire world of which I’d always been ignorant and suspicious, that I’d almost hated.

ROBINSON: You’ve always had that relationship with him, since you met him the early ’70s?

IGGY POP: We’ve always been friendly. I never really got to know him well until 1974, in L.A. This was after Main Man dumped me, and he was a star. He was living there and I was really on the rocks, and he was looking for anybody who would join in with his insane projects at the time. I then had a long think about it for two days. I really didn’t know if I wanted to get involved with him again, because I thought he might overwhelm me musically.

ROBINSON: What had he produced before, The Idiot and List for Life albums?

IGGY POP: Right, and I realized that I’d written some great songs with him: “China Girl,” “The Passenger,” “Nightclubbin,” “Lust for Life”—a lot of good work.

ROBINSON: Well, also, didn’t you think that trying to come back into the business in an important way—to get a deal—having his name associated with you could help?

IGGY POP: You know something? I felt the opposite. That was one of my big worries…I mean, he was known when I worked with him in the ’70s, but now he’s like a household shrine or something, and so huge, and totally across the board, TV and chiffon. I was afraid that writers would say, “Iggy didn’t have anything to offer on his own, so he got himself this huge guy,” and I was afraid that my own fans, who are probably not Bowie fans, would give me a backlash.

ROBINSON: I think, in the end, your fans know that you have done some great work together, and also that he has been inflicted by you.

IGGY POP: Well, he has been; at least that’s what I heard. People ask me what we’ve contributed to each other, and if you want to know what I’ve contributed to him, you have to ask him. If you want to know what he’s contributed to me, it’s been professional, teaching me the necessity of hard work, organization, and, more than anything, to have a wide, wide interest in people who are doing things a lot differently than you are.

ROBINSON: He’s a very good friend to you, too.

IGGY POP: Yes. He’s always accepted me as I am and listened to my ideas in a way that my early coworkers in bands never would. The guys in The Stooges would say things like, “Listen, Ig, your theory’s great, but let’s all have a beer, screw some girls, and do a gig.” Basically, I like David very much. I like spending time with him, and we have a very good relationship.

ROBINSON: You said something about worrying about being broken-down rock star. Have you felt like that?

IGGY POP: Yes, absolutely. I was feeling that I was the in the dead-end circuit from 1980 to 1983, and I didn’t know what else to do. I remember doing a show in some college town, in a tiny club, and afterward some fans came back. I thought I had done good gig and they were going to tell me that. But they looked at me very seriously and were shaking their heads, and they said, “Iggy, you deserve better than this. You shouldn’t be here.” And I wasn’t so stupid that I didn’t realize the implications of what they were saying. In my live work I was going for the quick thrill, rather than spending time concentrating on my voice. I figured I’d get on, make as many quick movement as possible, dance my ass off for five minutes, move into the insult portion of the evening, and then, at the end, create some kind of chaos until the 55 minutes were up.

ROBINSON: One more thing—are you still plagued by the Entertainment Tonight kind of reporter that refer to you as “Iggy, who used to slash his face and throw up on stage”?

IGGY POP: Lisa, I swear to you, almost 70 percent of the reporters not only ask me that, that’s the main focus of what they want to know, and if I try to avoid it, they come back to it, their eyes gleaming. The two words now are the class and the cutting. Or the bleeding… About eight years ago, all they asked me was about heroin. Now it’s all this.

ROBINSON: Aren’t the two connected?

IGGY POP: I don’t know. [laughs] Now I tell them it was just an illusion. Or I say, “Oh, I was so discouraged.”

ROBINSON: Do you actually remember?

IGGY POP: Some of it, yeah.

ROBINSON: I remember one throwing-up incident at the Electric Circus, and some hitting in the face with a microphone.

IGGY POP: One night at Max’s [Kansas City] I fell on a glass and I bled… and it was a big deal, apparently. But it never was the focus of what I did. People come to me, though, and talk about my “self-destructive image” and I say, “What self-destructive image? I’ve been out there, giving you this really good rock ‘n’ roll, with a good beat, this unpackaged show, that comes to your town, for 18 years.” A lot of people would bite off their own right arm to have the chance to do what I’ve been doing.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE NOVEMBER 1986ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.