Lemonade and the Deep Blue Sea

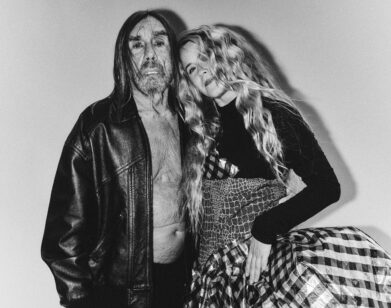

IMAGE COURTESY OF JOHN VAN PAMER

Sugary, refreshing, and pitch-perfect for summer: nothing pairs with these long August days quite like Lemonade. The San Francisco-cum-Brooklyn trio creates energizing, invigorating dance music that blends familiar ingredients into a brilliant audio combo. Part laconic vocals, part pulsing strobe lights, part bad drug trip, and part great drug trip, Lemonade’s sound is early ‘80s electro splashed with ‘90s club culture. They’ve opened for Neon Indian, played MoMA’s PS1, headlined Greenpoint’s House of Vans, and announced a European tour.

If you haven’t already heard their sophomore album, Diver (True Panther) blasting from every stereo in Williamsburg this summer, do yourself a favor and take a long, cool listen—or, better yet, attend their next New York show tonight with Teengirl Fantasy at the Rocks Off Concert Cruise. Recently, we talked with Lemonade’s Callan Clendenin, and the topics of conversation were as diverse as Diver‘s musical references: nostalgia, night swims, Bay Area radio, Crown Heights backyard dance halls.

ERIN BRADY: So, your music has been described by BBC Radio 1 as “agile, hedonistic pop music.” How do you feel about making audio hedonism?

CALLAN CLENDENIN: That particular description was on our first record. It was, I thought, kind of strange, but I liked it because our first record was not pop music really at all. I feel more like that is sort of what our music has become. At the beginning, it wasn’t pop music, it was more noise music. I kind of wish this record were more hedonistic and less sort of reflective. I think what happened was that too much of it was written during really, really bleak winters.

BRADY: Yeah, it seems like there are a few heavier themes on the record. Is this at odds with the pop sound?

CLENDENIN: It’s kind of interesting to me—the way people analyze lyrics. I mean dance music, pop music, like Whitney Houston songs or Janet Jackson songs, will be these really bright pop songs and when you listen to the lyrics, they’re always about longing and how much your heart hurts. Euro dance has been based on that; like these epically sentimental, happy moments with the most pained lyrics. Can you imagine someone reviewing Haddaway’s “What is Love?” and being like, “This is dark, dark, miserable…?”

BRADY: [laughs] Yeah. Fair enough.

CLENDENIN: “This poor sad man!” But, it’s not really about that. It’s about emoting and expressing. Also, with a lot of the Latin music I like, it’s like, “This is my heart and I’m crying for you.” I really like that. I like it in contrast with sort of more disaffected, cool lyricism. This record really was me getting into the role of what I thought a pop singer should sing, but not really for any reason beside that it matched what the song sounded like for me. It sounds like “Miss You Much,” and I was like “Well, what would Janet sing about?” I don’t know—I’m not going to sing, sort of like, indie lyrics about a vacation I had or something. I’m just not going to go there.

BRADY: I guess it all kind of depends on perspective, what your listeners bring to the table—

CLENDENIN: I think, unfortunately, I don’t get to pretend to be thoughtless. People are always going to think about the processes that go into our songs, which I think is a good thing so long as people don’t analyze to the point of not enjoying the music.

BRADY: Speaking of the processes that go into your songs, how are they written? Are they group efforts?

CLENDENIN: Yeah, I mean, some songs are more one person than the others. We all write on our computers. Some songs will be pretty much written before anyone else gets to it. Yeah, yeah, we all write the music actually.

BRADY: The record is in some ways a mix tape, with lots of different references—is this a result of you all collaborating together? Do you have similar or different musical tastes?

CLENDENIN: We definitely all have different tastes, but we share an appreciation of a tremendous amount. Really, how I know Ben and the band is Ben was working at a record store, a really big record store, and I would just go in and talk to him about records all the time.

BRADY: That makes sense.

CLENDENIN: He was way ahead of most people. He was one of the only people I could talk to about understanding dance music and electronic music and also, sort of, normal record-store guy stuff. In terms of all the different reference points, we’ve just listened to so much stuff over the years and usually when we’re writing, we don’t have any idea in mind; we’re just messing with stuff. So, anything can come out of us in that sense, but we don’t really have like a strict vision for what we’re trying to write. Like, I didn’t know what Diver was going to sound like at all.

BRADY: Really?

CLENDENIN: Yeah, going into it we weren’t really trying to replicate anyone’s style. I think it was surprising to us that that happened.

BRADY: That’s interesting. What are some of the references that you can pick out of the finished product?

CLENDENIN: This last year or two we used a lot of ‘80s, funk-based, sort of beachy sounds, like records that we associate with the beach or tropical funk. A lot of that snuck into UK electronic music at the same time that it snuck into our record. I don’t really know what it was, but it felt like the next step that needed to be made. It was the antithesis of the sort of IBM-y, like post-dubstep that was being made.

BRADY: Is that the reason for the record’s title, Diver? Or, if not, why Diver?

CLENDENIN: I don’t really know, actually, where the title came from. There is a lyric in one of the songs where I sing, “I heard you used to be a diver and you never broke the water.” I kind of know what the song means, and I kind of don’t. I don’t want to get too much into it. The lyrics and the scenes in that sort of encapsulate a lot of what the record’s about. There are a lot of aquatic scenes through it. When I write songs, I get certain images in my head, and that’s kind of how I fit the record together. There are actually one or two songs on the record where the images in my mind, the colors, don’t match the colors of the other songs and it bothers me, but I’ll never tell people, because I don’t want them to be like, “Oh yeah, it doesn’t fit.”

BRADY: What were you seeing for this record?

CLENDENIN: I was seeing a lot of like a pool at night, a lit pool at night.

BRADY: I like that image. That’s fitting.

CLENDENIN: When we were writing the music, I was thinking of all that. Also, there’s a record by Cluster or one of those guys that’s sort of a German New Age synthesizer thing and there’s a guy swimming—it’s very German—like he’s very muscular and he’s got diver shorts and he’s swimming in the ocean. I was really inspired by that image and by thinking about the solitude of being a diver. Also, I liked the idea of transitioning from dimensional states. So, all of that sort of played in, but I didn’t know exactly what I was trying to say with it. It’s just a theme that made sense, and everyone else seemed to agree.

BRADY: With all of that in mind, I’m going to have to listen to the album again. Also, I think that that title would also rationalize some of the musical references and nostalgia in the music. Are there any records you really remember listening to as a kid?

CLENDENIN: Honestly, my brother and I would listen to a radio station called X100 that was a dance, like high-energy, freestyle, Euro pop, and R&B radio station all rolled into one. It was a lot of freestyle and a lot of pop. I remember the first time I heard Madonna’s “Vogue” on it—

BRADY: [laughs]

CLENDENIN: [laughs] —and thinking it was really amazing. It was kind of like more interesting stuff, but also just like Tiffany was still being played on it and Taylor Dayne and all those freestyle hit songs were played on it, as well as old electro. I think maybe because of the Latino influence in the Bay Area there were also artists like Stevie B. and stuff, which I think most people don’t think about outside of like growing up in Miami or something. We used to tape the show on cassettes. I definitely internalized that music for some reason more than most people do because it’s supposed to be kind of light and whatever. Pop dance radio is sort of my nostalgic process.

BRADY: Yeah. The idea of the mix tape seems to inform Diver a little bit. It’s too bad those radio stations don’t really exist anymore.

CLENDENIN: Yeah, totally. Actually, sometimes I listen to Shep Pettibone sessions from the ‘80s on YouTube. Shep Pettibone produced “Vogue,” among other things. He produced tons of pop, like early Madonna. He was also an early remixer. He actually mixed other people’s songs and extended the breaks and added drum machines. You can listen to his DJ sets on YouTube from KissFM in New York. Another thing that got into me was being in New York and thinking about its legacy of great dance music. The radio in New York is still so amazing. I live in Crown Heights, and the amount of amazing Caribbean music I get to hear on the radio is awesome.

BRADY: I’m sure in Crown Heights, you don’t just get to hear Caribbean music from the radio, but also like every passing car and every bodega.

CLENDENIN: [laughs] Yeah. There’s an apartment complex a couple blocks away that has a backyard dancehall—

BRADY: Awesome!

CLENDENIN: It’s super loud.

BRADY: Well, awesome and not awesome at the same time.

CLENDENIN: I’m way into it, personally.

DIVER IS OUT NOW. LEMONADE PLAYS THE ROCKS OFF CONCERT CRUISE WITH TEENGIRL FANTASY TONIGHT. FOR MORE ON THE BAND, VISIT THEIR FACEBOOK PAGE.