Kweku Collins Between States

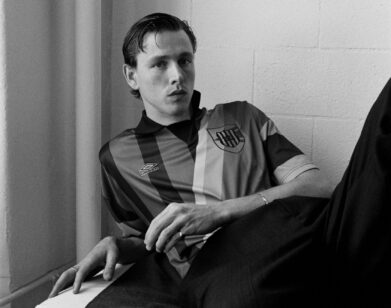

PHOTO: COOPER FOX. STYLING: RACHEL LESSING. SHIRT: JUGRNAUT. PANTS: LEVI’S.

In another life, hip-hop artist Kweku Collins might be a sophomore in college studying sociology. He’s fascinated by how people deal with those around them, and likes to examine the inner workings of relationships. In this life, the 20-year old Illinois native was signed to a record label (Closed Sessions) by the end of his senior year of high school, and channels that fascination into making music. His debut album, Nat Love, came out just over a year ago, and last Friday he released an EP, grey, which sees him explore the many dualities he’s been placed in as a creative, biracial young man: white vs. black, relationship vs. profession, practical college path vs. risky recording artist career.

“It’s very indicative of the place I was at when I was making the music,” says Collins of the EP, pointing to the frustrating feeling of not quite belonging as a source of inspiration. “It’s using the color grey as the larger metaphor for what I was going through.” Collins has learned to embrace existing in a series of “grey areas” or in-between states. “Grey is very humble, but when it needs to be, grey can be very bold. It’s very opposing in the way that it’s unified, being that it collects these two polar opposites and then turns them into one cohesive thing. It can be very cold and yet it can be very warm. It’s a lot of clichés that meet in the middle.”

When Interview recently spoke to Collins by phone, he was fresh from a visit home to Evanston, Illinois and riding the wave of wrapping his EP. He has other projects in the works, including his second full-length album, but for right now, he’s enjoying grey and “just being.”

KATRINA ALONSO: How did you decide on the different styles that went into writing these songs?

KWEKU COLLINS: The writing for each song wasn’t really a conscious, “Okay, I’m going to make this song and I need this kind of vibe for this to come after this,” or anything like that. It was more, “How do I feel in this moment?” And then I’d start. Like the guitar for “Youaintshit,” I started that off with just the guitar, and then how that guitar made me feel, and then, once the song was built, I could add that puzzle piece to the overarching soundscape—how it carries along the plot, not maybe so much in the literary sense, but the plot of the project as a storyline. It wasn’t really a conscious effort of, “Do I need this? Yes. I need this to go here.” It’s more how I feel.

ALONSO: You called the project a storyline, so how did you decide on the order of the songs?

COLLINS: For me, it’s kind of half and half. It’s weighing out the cohesion of content versus cohesion of sound. So, you listen to the first three songs of the EP—”Lucky Ones,” “Aya,” and “Jump.i”—those songs could be their own trifecta right there. Those songs merge together very easily. Then if you go “Jump.i,” “International Business Trip,” “Youaintshit,” and “Oasis,” that tracks these two parallel storylines, which is career versus the relationship and how those two intersect; that’s the predominant cohesion between those songs. Then you’ve got “Things I Know” and “Dec. 25th,” which are both songs that address death, but also sonically share piano, which is the line of cohesion between those two. Then there’s the outro, which is wrapping up everything into one song and putting it all into this period at the end of the sentence. Together, all these acts form a larger screenplay, in a way.

ALONSO: I read that your musical influences are really varied. You listen to Jimi Hendrix, Black Sabbath, Kendrick Lamar, Tame Impala. How did you get introduced to all of those artists?

COLLINS: They came from a lot of different sources. My dad and my grandfather both put me onto Jimi Hendrix and the Beatles and Bob Marley. Then there were the homies that put me onto Kendrick Lamar and Tame Impala and shit like that. It was also me discovering music on my own, where I started listening to Bob Dylan and I started listening to MGMT. I guess it’s fitting that it’s so scattered as far as what I listen to, because who I got it from is so scattered.

ALONSO: You mentioned your dad, and I know you have a musical family. What was it like growing up with a Latin and African percussionist for a father and an English teacher for a mother? How do you think they influenced your music?

COLLINS: The one thing that my parents were really adamant about was being creative and paying attention to the creativity that I had and using it. My mother would always encourage me to write, whether it be poems or short stories, or even draw pictures, or songs; whatever it may be, she’s always like, “Write and read.” My father, on the other side, we always had drums in the house and he was at home with me a lot of the day before I went to school, so he’d be drumming in the house with me, and I’d be doing what he’s doing, so I’d be drumming as well. I was just jamming every single day for however many hours out of the day. My mother, she was a dancer before she became a teacher, so I remember there was that whole other aspect of rhythm in my life.

ALONSO: Did she ever make you dance?

COLLINS: Nah. I wanted to, though! We used to watch So You Think You Can Dance when I was a kid, and I was always like, “Whoa, this shit is crazy.” I always wanted to be a modern dancer.

ALONSO: You’ve mentioned before that your family kept you humble about your craft and made you want to progress. What’s your dynamic with them now that you’re this famous artist?

COLLINS: [laughs] It’s the same dynamic, really, beause I’m not famous, it’s not like that. And even if it were, me and my family, we’re not really people like that, who will switch up if you get famous or some shit. I’ve still got problems communicating with my siblings and we all still have our little quirks, but at the same time, I’m still their little brother. My father is still my father and we still kick it like we’ve kicked it before. I think that it’s just part of getting older, how they see me. The media, they never really get how it’s like, how my family views me. They’re family. All my siblings helped me before I could help them, so things really aren’t even going to change. If anything, this music has made me closer to my siblings because it’s given me the opportunity to see them. They’re all settled in New York, and so every time I’m in New York City, I get to see them.

ALONSO: You once said, and this is a really cool quote, “I found that not belonging in one places helps me feel like I could belong in any place.” Do you still feel that way, or do you feel like you belong to a specific place now, two years after you graduated from high school and a year after your debut album came out?

COLLINS: You know what? That always changes for me. Now that I’m a little bit older, I feel like it’s changing, where I look at the world in different ways now: the way I look at things racially, the way that I look at things as personal. When I was in high school, I got along with the black kids, I got along with the white kids, and I in part attributed that to the fact that I’m biracial. I mean, I’m not a fuckboy, so of course I get along with most people. I feel like if you’re not shitty as a person, you’ll get along with most people. But I still feel like having the perspective of being biracial allows me to flow socially more. Whether or not I feel like I belong places, that’s more on me, personally.

In most cases, I don’t really feel like I belong. Unless I’m home, I don’t really feel like I belong anywhere. [If] it’s a new place, I become acclimated to that place and I become accepted to that place, and then I really do feel like I belong there. But with that being said, I think there is something remarkable about just being comfortable with yourself as a person. I do think that as long as you’re very secure in that, then you can be you anywhere. In that sense, I think belonging is a very interesting concept because it depends on how you look at it, and from whose perspective, and where you are, and what you’re doing. It’s very complicated to me.

GREY (CLOSED SESSIONS) IS OUT NOW. FOR MORE ON KWEKU COLLINS, VISIT HIS WEBSITE.