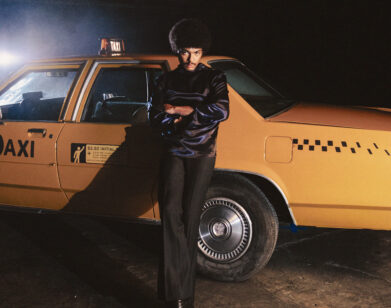

John Digweed Spins Into Goldâ??and Beyond

John Digweed was once asked which actor would play him in a film of his life. He chose Paul Scholes. His answer is instructive on two counts: firstly, Scholes isn’t an actor—he’s a soccer player (Digweed is a man of few theatrics); secondly, Scholes is celebrated in England for a combination of his technical brilliance and his lack of interest in the fame that goes with it. While Digweed’s career is inarguably distinguished, he makes no room for the excess baggage many globetrotting musicians seem to enjoy. A decade ago, Digweed was voted the world’s best DJ in the influential DJ Mag. Since then, his impact has only grown. His Bedrock label, established in 1998, is responsible for developing talents like Danny Howells and Jimmy Van M; his radio show, Transitions, broadcasts to 14 million people in 40 different countries. Digweed tells Interview the show is a way of showcasing his work; it also generously opens a window of opportunity to guest DJs, who prepare hour-long mixes well in advance of the weekly broadcast.

Two partnerships have been central to Digweed’s professional narrative. With Sasha, he developed a relationship responsible for several pioneering mix collections. The pair produced assiduously edited records, whose artistic merit collapsed any notion that house music was geared exclusively towards rave culture. Their original Renaissance collection was the first club mix to go gold in the UK. As a producer and record label boss, Digweed’s creative partnership with Nick Muir—both in production and in the management of Bedrock—continues to flourish.

During the ’90s, Sasha & Digweed formed a legendary New York residency at Twilo. Just before Digweed’s return to the city (to play Electric Zoo tomorrow), he talked to Interview about New York and offered a historian’s perspective on the music that took him there.

NICHOLAS MALTBY: When you were playing at Twilo, did you live in New York?

JOHN DIGWEED: Well, I kind of lived there in a roundabout way. I was there every month for over five years, so yeah, I was pretty much a resident; but I didn’t have an apartment or anything.

MALTBY: That must have been hectic.

DIGWEED: Yeah, but when you get the opportunity to play at what’s probably the best club that’s ever existed, every month, you’ve got a natural adrenaline that sparks into you. There was never once I got on that plane at Heathrow and thought, “Ah, I’ve got to go to New York tonight; I don’t wanna go!” I considered myself extremely privileged to be part of the time, and also it was a fantastic time in New York clubland.

MALTBY: Does the city have a special place for you?

DIGWEED: New York is a very special city—when you spend five years, every month going somewhere, you have a lot of fond memories of it. But I’m also one of those people that doesn’t want to spend too much time looking at the past, who wants to be looking forward. So since Twilo closed, I’ve had great nights at Pacha, District 36; and Electric Zoo last year was fantastic.

MALTBY: How would you define New York’s association with house?

DIGWEED: Well, as far as dance music goes, it had quite a big impact—I never went there, but if you go back to Disco 2000, with Keoki, he was putting on some very futuristic music—right through to all the clubs with the Limelight, and then The Tunnel, Area, Sound Factory, Sound Factory Bar. There was a hell of a lot going on in New York in the late ’80s and ’90s. I remember when I was first doing Twilo, it would be packed, but you’d have four or five thousand in The Tunnel, you’d have Area with four or five thousand, you’d have Club Exit or something like that, so probably on a Friday and Saturday night you’d have twenty, twenty-five thousand people out each night, going clubbing. New York definitely led easily with the sound systems because of Richard Long Sound Systems, which were doing installations at the Paradise Garage. You know, people talk about that sound system like no other sound system on earth. So New York’s always been very prominent when it comes to clubbing: they do it properly and they want the best sound systems. District 36 has got the Gary Stewart sound system in there, which is amazing, Steve Dash with his Integral Sound—the sound is a very important part of New York clubland.

MALTBY: How do you differ your sets when you’re playing outdoors?

DIGWEED: I’m one of these DJs who likes to play true to myself, so I’m not gonna be throwing in some rock bootleg mashup mix of some record to get a reaction. Sometimes it does amaze me, you go to festivals and DJs think, “Oh, I need to play big crowd-pleasing records.” You don’t need to spoon-feed the crowd.

MALTBY: You’ve resisted laptops when performing; what equipment do you use?

DIGWEED: I use the CDJ-2000. I’ve always been CDs and vinyls. I tried a laptop for about a month and I didn’t really feel comfortable with it.

MALTBY: In your sets and on your radio show, you rarely intrude on the music. You strike me as someone whose focus is all-consuming.

DIGWEED: I love what I do. I’m living the dream. I know that sounds corny, but I wanted to be a DJ from about the age of eleven or twelve, so the fact that I’ve spent over half my life living out my dream and still doing it at a very high level, I consider myself very lucky. But I’ve also worked extremely hard and I still work really hard, maintaining my career; but the radio show gives me an opportunity to promote new talent. As a personality, I’m not one that likes to be center stage. It’s not about me, it’s about the music. I just want people to listen.

MALTBY: How far does that inform the kind of music you end up playing?

DIGWEED: I’ve always strived to find those records that people don’t know, but they actually go “Wow, what is this?”—and they go crazy to it. To me, that’s more rewarding as a DJ, and that’s what I always thought a DJ was supposed to do: it’s about educating people. That was what made the rave scene in England, and the club dance scene, so popular, because it was escapism from what people heard on the radio and on the TV and stuff like that. Now there seems to be a commercial edge to stuff and people are reacting to stuff they’ve heard on the radio all day long: to me, that’s not what youth culture should be reacting to.

MALTBY: You have trumpeted the virtues of David Guetta. Are his kind of collaborations with artists from other genres something you’ve ever contemplated?

DIGWEED: David’s been DJing probably about the same time amount of time as me. He’s worked incredibly hard: he’s stuck to his guns. He makes music that he feels really passionate about—when he did that record with Kelly Rowland, he really tapped into something which no one had done before. For me, making music with different genres is not really something that I’m that into, but it works for David.

MALTBY: What other genres do you listen to?

DIGWEED: If you saw how many demos and promos I get sent every day, what time I do have left is usually trying to sleep, or doing something else! I get sent between 30 and 50 demos every day, if not more!

MALTBY: And you take time to try and listen to the majority of them?

DIGWEED: Yeah, you try and whittle your way through. But I only respond to the stuff I like.

MALTBY: How would you say that your style of mixing has developed during your career?

DIGWEED: It’s always been about trying to choose music that is good, current, and that I think is futuristic—but also, when I put a mix CD together, I’m not making a mix CD for that period of time; I’m hoping to choose records that people will look back at in five years time, and say, “These records still sound good.” That’s why when I put an album together, I usually spend at least two or three months making it.

MALTBY: What do house and techno signify to you in their current states?

DIGWEED: House is having a definite resurgence, but I think people are confused when they say Swedish House Mafia is house, because that’s more commercial house music, whereas if you went house music, you’d be thinking DJ Sneak and more old-school New York and Chicago guys. And if you look at techno a few years ago, it was quite tough, industrial, quite fast, but now it’s a lot slower and cooler: it’s almost house-ier. Everything seems to change all the time. People take influences from different styles: that’s what keeps it exciting. I’ve just downloaded a load of tracks from labels like BPitch Control and Ovum—straight away, I’m going into the weekend knowing that I’m going to have four or five new tracks to add to the ones I’ve already been sent this week.

MALTBY: If you had to select three of your tracks for someone on a desert island, what would you choose?

DIGWEED: “Heaven Scent” was a huge record for Nick and myself. I think it really captured the moment. We put our minds together—we wanted to make a massive record because we were doing a club night at Heaven in London; we wanted to create an end-of-the-night record and that just came together. It did what it said on the tin. I’m happy with our remix of “Cowgirl” for Underworld. And our track “Gridlock,” as well, we did like a 25-minute version. Quite self-indulgent—but it was nice to do something that took on a long journey!

JOHN DIGWEED WILL PLAY THE MAIN STAGE AT THE ELECTRIC ZOO FESTIVAL AT NEW YORK’S RANDALL’S ISLAND PARK TOMORROW. FOR MORE ON THE ARTIST, VISIT HIS WEBSITE.