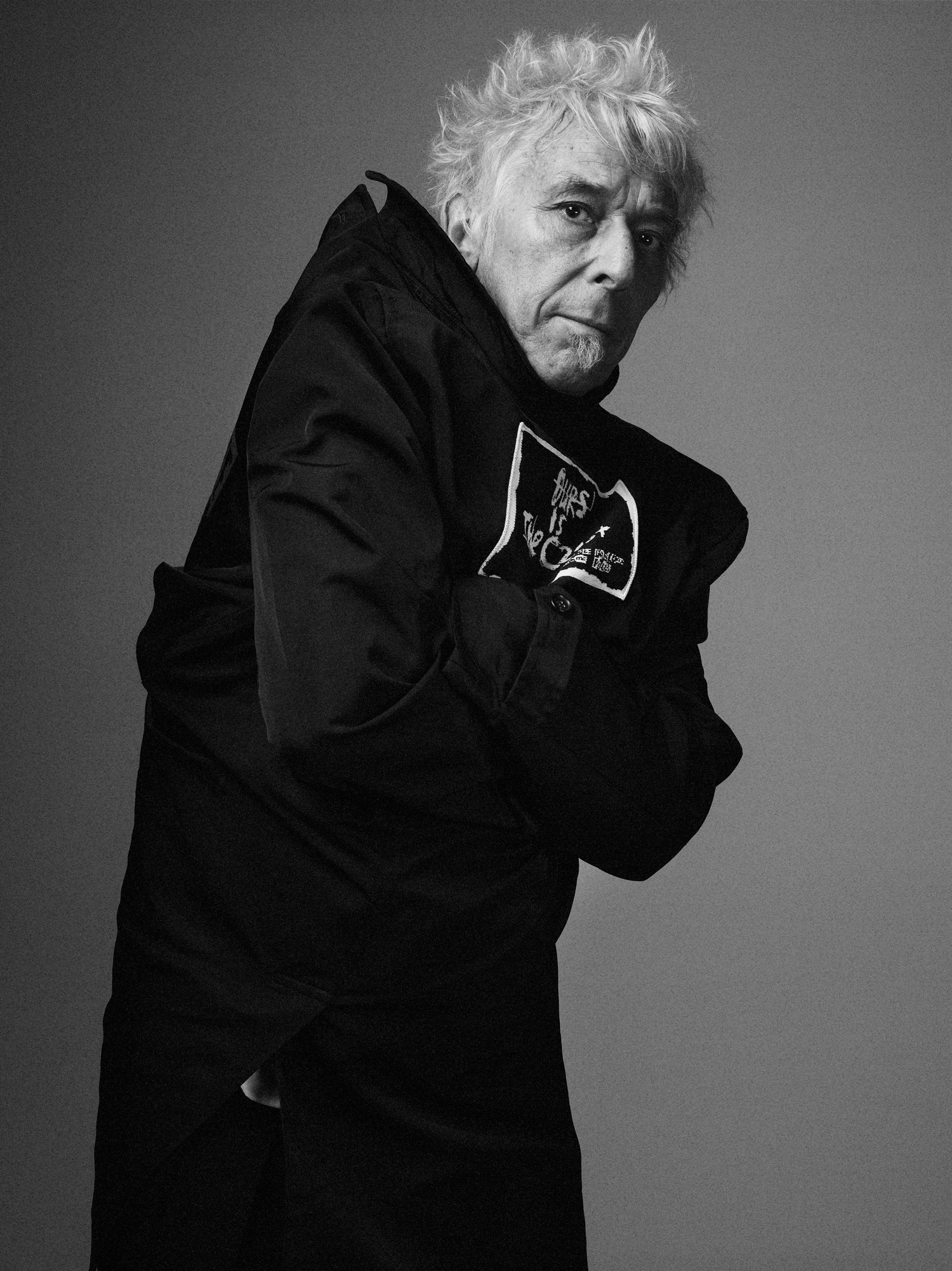

John Cale

The Vietnam thing was going on, and a lot of people in Europe seemed to take what we were doing as anti-Americanism . . . I think there was a good dose of that in our popularity over there.John Cale

Rock-‘n’-roll has always thrived off its status as a phenomenon that exists at once in the margins and in the mainstream. But few practitioners of actual rock-‘n’-roll music have moved between the more rarified worlds of art, avant-gardism, youthful rebellion, and disenfranchisement, and the larger world of pop as easily and as intrepidly as John Cale.

Born in Wales, Cale arrived in New York City in 1963 at the age of 21, a young classical-music prodigy who had gained the attention of composer Aaron Copland. Cale, though, quickly fell in with the burgeoning experimental music scene of the era, crossing paths with the likes of John Cage and La Monte Young. However, it was Cale’s co-founding of The Velvet Underground in 1965 with Lou Reed, Sterling Morrison, and Angus MacLise—who was quickly replaced by Maureen Tucker—that proved an early turning point. With the support of their original patron, Andy Warhol, The Velvets, of course, went on to become one of the most influential outfits in rock ‘n’ roll history, combining the raw noise and radical sonic explorations of the “serious music,” with which Cale and his new bandmates had become infatuated, with clever pop songwriting and the multimedia kineticism of the flourishing downtown art world. Adding German model-turned-chanteuse Nico to the mix, the Velvets spent nearly two years working up to their debut album, The Velvet Underground & Nico (1967), a record that broached then out-of-bounds subjects such as S&M and drug use in songs like “Venus in Furs” and “Heroin” while offering a vivid reimagination of pop music (and pop stardom) that has continued to cast a long shadow over multiple generations. “The first Velvet Underground album only sold 10,000 copies, but everyone who bought it formed a band,” or so goes the infamous quote often attributed to Brian Eno. Indeed, The Velvet Underground & Nico has done more to shape both the ethos and the direction of a certain kind of rock-music-as-art than virtually any other record to come out of the late 1960s, a time when pop music itself was beginning to assume a new cultural weight. (Sonic Youth and R.E.M. were both close students of the Velvets, and Pitchfork has helped create a cottage industry around celebrating bands that owe them a significant debt.)

The relationship, though, between Cale and Reed was always an uneasy one, and in 1968—the same year of his brief marriage to designer Betsey Johnson—Cale left The Velvet Underground to branch out on his own. The body of work that he has produced since then has proven both pleasantly diverse and remarkably vital. As a producer, Cale helped craft genre- and career-defining debuts by The Stooges (The Stooges, 1969), Patti Smith (Horses, 1975), The Modern Lovers (The Modern Lovers, 1976), and Happy Mondays (Squirrel and G-Man Twenty Four Hour Party People Plastic Face Carnt Smile [White Out], 1987), as well as three records by Nico, amongst numerous albums. As a sideman and collaborator, he’s worked with everyone from Eno to Terry Riley and Nick Drake. And as a solo artist, Cale himself has been both prolific and adventurous, moving effortlessly from compositional excursions like The Academy in Peril (1972) to the literary chamber-pop of his masterpiece Paris 1919 (1973) to the sneering unhinged aggression of subsequent albums like Fear (1974) and Slow Dazzle (1975). After leaving the Velvets, Cale also continued to maintain a longtime association with Warhol, who designed the covers of two of his solo albums (The Academy in Peril and 1981’s Honi Soit). Following Warhol’s death in 1987, Cale unexpectedly reconnected with Reed to create a memorial album, 1990’s Songs for Drella, which led to a brief, fractious Velvet Underground reunion three years later—the bitter aftermath of which led both Cale and Reed to pledge that they would never work together again. (Save for the group’s 1996 induction into The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, they haven’t performed together since.)

Cale has continued to work vigorously in recent years, releasing multiple albums and EPs, performing, and finding new (and occasionally unexpected) collaborators and audiences. At 70, he still revels in the shock of the new, as evidenced by his latest album, the conspicuously titled Shifty Adventures In Nookie Wood (Double Six). The record is, in typical Cale fashion, a study in contrasts, an album that manages to be both stately and funky, raw and techno-forward (yes, that’s a vocoder on “December Rains”). October also sees the release of a new 45th-anniversary edition of The Velvet Underground & Nico, featuring numerous outtakes and extras, including a series of previously unreleased recordings made during rehearsals at Warhol’s Factory and a November 1966 concert at the Valleydale Ballroom in Columbus, Ohio. “I’ve always admired John,” says Brian Burton, a.k.a. Danger Mouse, who worked with Cale on Nookie Wood‘s beguilingly perverse lead track, “I Wanna Talk 2 U.” “He’s produced some of my favorite albums, and yet he’s got his own special thing going on as an artist . . . It’s a place I’ve been trying to get to myself.”

Actor Willem Dafoe, who was working in Rome, recently caught up with Cale in London, where he was gearing up for the European release of Nookie Wood—and, as always, plotting his next move.

One of the things that has been really interesting in talking about this new record is how misunderstood some of the lyrics have been. In France and Germany, I had to explain what nookie was.John Cale

WILLEM DAFOE: You probably feel this, too, but there was a time where I was the youngest one in any group, and now when I turn around sometimes, I’m the oldest one in every group. It just seemed to flip-flop one day—it wasn’t a gradual thing. Have you noticed that at all?

JOHN CALE: Well, I’ve just recently started doing the promo bits for the new album, and the funny thing is that the people who come to talk to me about these things seem to be getting younger. It’s like the people who like the music are all young kids and they’re on top of you—they know all about what you’re doing, and they’re excited and animated about it. So it’s a lot of fun.

DAFOE: Let’s talk about the record.

CALE: We could, yeah—but I also want to talk to you about The Wooster Group, too [the renowned experimental theater group that Dafoe began performing with in the late 1970s].

DAFOE: The Wooster Group isn’t me anymore—I had a split with them [in 2004], but luckily I’ve still found stuff to do. Lately I’ve had a really good time touring with Bob Wilson’s show, The Life and Death of Marina Abramovic. I even get to sing in it.

CALE: So you don’t think you’ll find another group situation to get involved in?

DAFOE: Oh, you know . . . I was with them for 25 years. We worked every day—I mean, it’s possible. The other thing is, when we started out, we were a bunch of kids who weren’t theater majors. We were coming from different places. Some of us were training in architecture, some of us were musicians . . . It was that time where everyone around me was making stuff, and none of them had the credentials. In the ’70s, there was an explosion in New York of music, Super 8 filmmaking, and loft performances, and that’s what it kind of came out of. People were just not thinking about tomorrow. We had a small space, which was all we had, and we just kept on making work. Everybody hated us for a long time. Everyone thought we were useless. Then slowly, we got a reputation—mainly through doing things in Europe. I’m sure that you have had parallels in your life.

CALE: Yeah. [laughs] The Velvet Underground sold a lot of records in Europe. I think our reputation there was far more intact than anywhere in the U.S.

DAFOE: Then the next time you’d be in New York, people there would get proprietary—like, “Oh, I saw them at the Beaubourg. They were fantastic.” [both laugh] But it seems like a lot of the really special work that you’ve done, like that ballet you did [Ed Wubbe’s Nico, featuring music by Cale], was possible because of your reputation in Europe. You would never have received the same kind of support in the States.

CALE: That’s true. The weird thing about all of this stuff with The Velvet Underground was, at the time, the Vietnam thing was going on, and a lot of people in Europe seemed to take what we were doing as anti-Americanism and enjoyed it for that. It was strange—I think there was a good dose of that in our popularity over there. We certainly didn’t revel in that fact. We didn’t care about anything anyway. We didn’t care about what anybody thought. It was more like, “Let’s see if we can get it together to just play tonight . . .”

DAFOE: Before this interview, I was reading a lot about you, and one question that seemed to keep coming up was, “How did John Cale—this young, classically trained musician from Wales—slip so easily into the experimental music scene as soon as he hit the ground in New York and then wind up starting The Velvet Underground?” It’s like, Are you kidding me? That’s exactly what was happening in New York at that time.

CALE: Yeah. Things were all wide open.

DAFOE: Socially, that’s what was going on. I liked being around those people when I was downtown. When I first came to New York, I thought I was going to be a regular actor, but then I’d go downtown and be more turned on by the people—I’d be excited by what they were talking about and what they were doing. I didn’t even think about what it meant. Do you remember a place called The Collective?

CALE: Yes! I mean, that’s where a lot of energy came from. It was a social thing—everything with the Cinematheque and 16 mm film, Harry Smith, Lenny Bruce, and all that. You know, we’re coming through New York in January to do a tribute to Nico at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, and then we’re doing Paris 1919 with the orchestra there.

DAFOE: How do you feel about going back and revisiting that stuff?

CALE: The thing is, Willem, the first time we did it, everyone said, “Oh, you just want to do ‘All Tomorrow’s Parties’ and ‘I’ll Be Your Mirror’ and that stuff.” But then, all of a sudden, there came this tsunami of young singer-songwriters who all loved Nico just for her writing. It’s grown and grown and grown and grown—there’s no end to it. So they all want to be a part of the show for the right reasons. It’s a great variety. There’s Joan as Police Woman, CocoRosie. But, you know, getting back to Europe for a moment, one of the things that has been really interesting in talking about this new record is how misunderstood some of the lyrics have been. In France and Germany, I had to explain what nookie was.

DAFOE: I wasn’t even sure if you knew what nookie was.

CALE: [laughs] Well, what I’ve been telling people is, “If you ask a girl if she wants to have some nookie, then she’ll know what you mean.”

DAFOE: There you go . . .

It’s too frustrating trying to work a system where you have to run back and forth constantly doing different things. But hiring somebody who can read your mind while you’re working is excellent.John Cale

CALE: Then there’s the wood part of it. I read this article years ago about some national holiday in Japan where the kids celebrate the last day of summer or something like that. They all go to this one particular place, a holiday spot—in my mind, I think of an island, but it’s a sea of trees. But everybody goes out and celebrates, and at the end of the day, when they lock the park up, the last people in are actually the police and ambulance services, because, for some reason, every year people go in there and commit suicide.

DAFOE: Wow.

CALE: In one part of the woods, the police will find somebody who has hung themselves; in another part of the park, someone will have shot himself . . . It happens every year, but they haven’t been able to figure out in advance what’s going to happen. But just the description in the article of how the variety of the people . . . Anyway, that’s where I got part of the idea for Nookie Wood, with that atmosphere of Blade Runner [1982] and all those Vietnamese announcements in the background. It’s really from that image. It’s the closest I’ve ever gotten to writing a song about that story.

DAFOE: The song “Mary” is the one that popped for me first, because of the vocals.

CALE: “Mary” is about bullying—high-school bullying.

DAFOE: You know what’s funny? I didn’t know that, and I don’t need to know that. I responded to it immediately. It’s a real strong, emotional song. Somehow the lyrics just stand on their own.

CALE: When you finish writing a song, putting the vocal together is kind of the penultimate stage. On this one—because of the subject matter—I really didn’t want to deliver it. I don’t think it’s the kind of song where you want to go in and . . .

DAFOE: Work it.

CALE: Exactly. There’s a quality that’s tentative and insecure, and I wanted to leave it like that.

DAFOE: What about “I Wanna Talk 2 U”? That one just jumps into your lap. Tell me about working with Danger Mouse on that.

CALE: He played the drums and the bass and some other things, and I added the other stuff. The feel of it is different from the rest of the album—it’s sweet, and it has a little bit of Detroit in it. At the end of the album, I was trying to get this loose kind of feel-you know, a little tambourine—and I wasn’t getting there. But he was just a step ahead of me all the time. A lot of stuff I did, I’d say, “Nah, forget that. That’s not going to work. Let’s do another idea.” But when I got the files back from Danger Mouse, I noticed that he’d taken things that I did in the verse that didn’t work and put them in over the chorus, where then it did work. So this is a guy who realizes that every little expression of somebody’s personality is valuable in some way or another in the making of the piece.

DAFOE: Do you usually have to find collaborators or do they come to you? Is it different every time?

CALE: It’s different every time. With Danger Mouse, here was a guy who was turbocharged—we got a lot of work done in a little bit of time. It was fun and it was scrappy, and we found all of these unexpected things that you’d never think you’d find. He was really so useful when it came to finishing a song.

DAFOE: I’m jealous. The problem with actors is we generally need another person to play with. I mean, as an actor, you can do one-man shows, but I think that’s a limited thing.

CALE: It is similar for musicians—you can’t do everything. It’s too frustrating trying to work a system where you have to run back and forth constantly doing different things. But hiring somebody who can read your mind while you’re working is excellent.

DAFOE: I hate to throw old quotes back at you, but I was struck that you said that you used to read Michael Ondaatje when you were stuck and wanted to be inspired. I thought that was beautiful because I know exactly what you’re talking about.

CALE: About The English Patient.

DAFOE: I like many of his books. Do you know his other stuff?

CALE: Yeah. He was the one who got Liz Calder [co-founder of Bloomsbury] at Bloomsbury to write me a letter that said, “I must now ask you to write a book.” She saw a performance with Michael Ondaatje and wrote me a letter, and when you have Liz Calder and Michael Ondaatje asking you to write a book, then you kind of sit up and pay attention. I was really flattered. But the thing about the book, the biography, was that I wanted it to be like reading your television and have visuals all over it. I got this artist Dave McKean, who has worked with Neil Gaiman, and he put it all together. It was exactly what I wanted. It had a lot of visuals and photos from my youth and my family—just molten visuals with different fonts all the way through it. I was very happy with it. But, you know, there’s a wall between literary publishing and what might be thought of as comics. So they really didn’t quite get it. I think what I need to do is start the book on an electronic database . . . But anyway, that’s a whole other story.

We didn’t care about anything. We didn’t care about what anybody thought. It was more like, ‘Let’s see if we can get it together to just play tonight.’John Cale

DAFOE: You mentioned that the people you’ve been talking to while doing promo for the album seem younger, but I’d imagine that your audience changes all the time. Does it?

CALE: Well, at times it has been a series of forced changes. In Europe, the promoters used to riot when they heard me coming along because I would make everybody stop smoking. That was about 10 years ago—”Oh, no. Cale’s coming. I never sell any beer and now he wants me to stop smoking?” [laughs] Very good. And then you do festivals like the Drum festival, and they say, “Are you sure you want to do this? Drum is a tobacco company.” And I go, “Yeah. Just put up ‘No Smoking’ signs and it’ll be fine.” But as of late, the audiences have all gotten younger. It just started happening about four years ago, and I have no idea why.

DAFOE: It’s probably about who gets out of the house and listens to music.

CALE: Yes, they’re all sort of curious. But at the same time, I like a lot of the younger bands that are around—a lot of the Williamsburg bands.

DAFOE: Who do you like?

CALE: Dirty Projectors. Then there are also a couple of hip-hop guys, like Chingo Bling, who’s from Texas. He has had a couple of big hits there-specifically, one of them is called “You Can’t Deport Us All,” which is like Tex-Mex. Then there’s a group called Not the 1s. They have a song called “You Dress Like an Asshole.” [both laugh] It’s all about the fashionistas, and it’s very funny. I mean, I don’t think he’s talking about Pharrell, who is one smooth-dressing dude. But I like the hip-hop guys a lot. There is a lot of drama in them. A lot of the misogyny, I don’t like much, but in general . . .

DAFOE: How do you hear about these guys?

CALE: I go trolling, surfing . . . The odd thing is that a lot of these people come from Snoop [Dogg]. Snoop definitely has a wide range of irony. There’s a quality in his songwriting that you don’t really expect.

DAFOE: I’ve always liked him.

CALE: He’s so funny—he has a song about Johnny Cash. There’s this one guy, Kokane, who worked with Snoop and has three personalities in his voice that come out in every song. He has this Marvin Gaye voice—a very high, true falsetto, which is very sweet. Then there’s the middle tone, which is warm and kind of crooning. Then, down below, he has a growl—and all of those voices will be singing the verse. He’s got a wicked sense of humor, too. You should check out this one song of his called “When It Rains It Pours.” It’s heartbreaking. He’s got that church thing in there.

DAFOE: You’re interested in so many different things.

CALE: You know, I went chasing after this complete will-o-the-wisp: There was this guy in France who I’d heard of, this famous lawyer Jacques Vergès. He defended Carlos the Jackal. He also defended some Algerian revolutionaries when the Algerian War was going on. And then he also popped up to defend the Khmer Rouge in the trial in Cambodia.

DAFOE: Yeah?

CALE: And this guy . . . I’m thinking that these are good left-wing credentials we’ve got here. And then I see that he’s written a play! He’s written a play starring himself about all the stuff he’s been involved in. And I’m thinking, Hey, wouldn’t it be funny if this thing would really work in English? And then I trip over a little documentary by Barbet Schroeder called Terror’s Advocate [2007], and it’s this guy talking about all the stuff that he’d done. It’s something that has really kept my interest over the years. This guy disappeared for eight years in the ’70s, and he wouldn’t say where he was, so when he popped up to defend the Khmer Rouge, it sort of made sense that that’s where he would have been. Some of the defenses that were put up for these nationalistic movements—some of them worked and some of them didn’t. But anyway, I was really fascinated by this guy.

DAFOE: So that’s something you’re thinking about.

CALE: Yeah. But watching the Barbet Schroeder documentary—I really respect Barbet Schroeder a lot.

DAFOE: Do you know him?

CALE: Yeah, I met him once. He said, “Look, don’t ever let anybody tell you that with American films people don’t get exactly what they want.” And I said, “What do you mean?” And he said, “Well, they do all of these marketing analyses and decide on what people want from a select group—and they’re usually right.”

DAFOE: I don’t agree with that at all.

CALE: No, I don’t either.

DAFOE: First of all, those focus groups can be led.

CALE: I’m sure they are.

DAFOE: I mean, you don’t show people a movie and say, “What’s wrong with this?” [Cale laughs] It would be like playing your record and saying, “What should we change? What’s wrong here? What sounds bad?” And just for their own sake, people will say, “Well, I like it, but I guess that the ending isn’t quite right . . . “

CALE: It’s like going to the doctor and the doctor says, “What’s wrong with you?” and you’re like, “What do you think I’m here for? To find out!” But Barbet Schroeder did another film years ago with Nicolas Cage that I remember was pretty good. It was called Kiss of Death [1995], and it was a remake of an older film—Richard Price wrote the screenplay. Cage plays this mafioso who slowly goes mad. There’s this one scene where he says something like, “You know, I’ve come to the realization that my name should be associated with this idea, and this idea is B-A-D. I am BAD—Balls, Attitude, and Direction.” I was quoting that one for months.

Willem Dafoe is an Academy Award–nominated film and stage actor.