Japandroids in the Moment

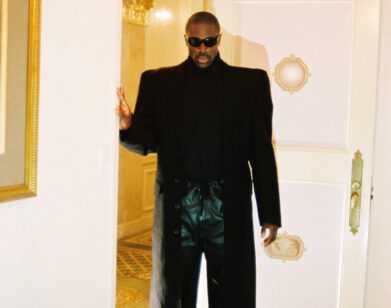

ABOVE: JAPANDROIDS’ BRIAN KING (LEFT) AND DAVID PROWSE. IMAGE COURTESY OF SIMONE CECCHETTI

Halfway through our interview with garage-rock duo Japandroids, in the sunny outdoor garden of a bar in Brooklyn, drummer David Prowse asks if it’s okay if he smokes. We don’t mind, we say. Then guitarist Brian King pulls out a pack, too.

“I figure we’ll just smoke at the same time, so then it’s just done,” King offers. “You don’t have to put up with it twice in a row.” They’re both very considerate, we observe. “We’re Canadian,” they answer, in perfect unison.

“We have to be,” King goes on. “It’s part of our visa to come play shows here: ‘Must be considerate to all Americans.’ Free trade, and all.”

King and Prowse’s unfailing politeness, and the studied thoughtfulness with which they answer questions, might come as a bit of a surprise to those familiar with their music, which is driving, insistent, and best played loud. Following the unexpected and delayed success of their debut full-length, Post-Nothing, in 2009—they’d planned to break up after releasing it, before the single “Young Hearts Spark Fire” became an Internet breakout—the band returned this month with the triumphant Celebration Rock, a whirlwind 35-minute paean to the right-this-second urgency of being young. Its first single, “The House that Heaven Built,” is our favorite of the year.

The same day the album came out, we chatted with King and Prowse about band bios, their preferred narrative mode, The Hold Steady, and why Celebration Rock may not be a summer album after all.

ALEXANDRIA SYMONDS: The bio you wrote for this album is long and extensive, and sort of funny and self-deprecating.

BRIAN KING: There’s two ways to write a band bio: Either you can get someone to write it, or you can write it yourself. Either way, it’s very difficult to take seriously. If you have somebody else write it for you, you have somebody who, maybe they interview you or they read a lot about you or they think they know what they’re talking about; and they write what they think will sell you to the world. Nine times out of 10, to be blunt, it’s just really flattering bullshit. It’s designed to make you seem better or greater than you really are.

And then if you write it yourself, it’s really easy to self-aggrandize or basically do the same thing–except it’s even worse, because you’re writing about yourself. So when it came time to do the bio, I decided that I was going to write the kind of band bio that I wanted to read from other bands that I liked. Something that contains a lot of valuable information, insight into the band, the history, and the recording of the new album, and stuff you might actually want to know—but at the same time, doesn’t strive to tout the band as something greater than they are and is, at its core, fairly honest and truthful and accurate. And that can do that with a little bit of humor and a little bit of, like you said, self-deprecation, and something that isn’t too serious.

SYMONDS: Do you think you have that impulse almost to a fault? I think the term was “not making the band more than it is,” but you guys are big. You’re allowed to bask in that to some extent—but you seem really hesitant to ever want to do that.

KING: Humility is sort of lost upon bands when they get to a certain point, and I don’t think we’ve reached a point where it’s not still imperative that we include humility everything we do.

SYMONDS: Do you think that’s partly because of the kind of unusual path you guys took from the beginning? How long it took to get started out, and then the fact that you got attention when you least expected it.

DAVID PROWSE: It definitely helps with not taking what we have for granted, and being aware that it can be fleeting and that popularity, to some extent, can be quite arbitrary. Post-Nothing could have, very easily, totally flown under everyone’s radar, and not really found that popularity. So I think it’s good to, especially when you start to get to achieve certain levels of success and start doing a lot of interviews and having a lot of reviews, it would be quite easy to get pretty full of yourself. I think it’s an important thing to try and keep yourself in check and just be aware that popularity doesn’t necessarily run in parallel to quality.

KING: I think the bigger music fan you are, the more painfully aware you are of all the little details that go along with all the bands you like. I can’t tell you how many band bios I’ve read, even of the same band, album to album, for such a long time—you’re just so hyper-aware of everything about the band on top of the music. The music, of course, is what draws you to the band; but if you’re a real fan, you have to know everything.

I think we’re the kind of band that the people who really like us have to know everything, so they’re going to read the band bio, they’re going to read the interviews, they’re going to read your reviews. So in every opportunity you have to actually be a part of the things that are written about you—the band bio, for example—you want to put in that the same personality, or the same earnestness, or the same whatever that you actually put into the music. You want that to be just as much a reflection of you as the music is or the photo is, or anything else that’s not specifically the music.

As you were saying, we’re not just a small band anymore. As your profile increases, you become more and more aware of how many people actually know who you are and are actually going to read these sorts of things and listen to the music, and you start to take those things a little bit more seriously and think about them more than you ever did in the past.

SYMONDS: Do these changes come gradually to you? Or does it come in fits and spurts? Do you realize “Oh my God, X-thousand people heard my last album, and Y-thousand people have already heard this one”?

KING: I think with the first record, they came really gradually, because it was sort of a slow start. It was more of a word-of-mouth kind of record. Its “success,” or its popularity, occurred over a longer period of time, whereas I feel like with this record it’s been more black and white. We wrote and recorded the record, and then it was like everyone discovered it within a very short amount of time. Everything you read or hear about the record has all occurred very recently, and so you don’t have as much time to process the evolution of the record as it’s going on. It’s sort of like, no one knew about it, and then everyone knew about it, and you kind have to come up with everything you need instantaneously.

SYMONDS: And you had anticipation to deal with this time.

KING: Yeah, exactly.

SYMONDS: I wanted to ask about grammatical register. It seems like you tend to write songs in the first-person plural—it’s “we,” or it’s “you and me.” You’re not telling stories about other people, or about things that are happening in any moment of time other than this immediate “you and me, right now.” Can you speak to that?

KING: Good question. That is something that I proactively try to do, lyrically. I didn’t understand how important it was to do that in the old days, because it just never occurs to you. And then, on our first record, some songs did do that and some songs didn’t do that. And you realize really quickly that the songs that resonate the most with people are the songs that you do that—because it’s inclusive to them. You’re no longer singing a song like, “This happened to me, hear about it.” It’s almost like you’re representing other people in the song that you write, and therefore, it’s incredibly inclusive.

Probably 99 out of 100 songs are introspective songs; it’s someone who’s singing about something that happened to them. That’s all well and good—I love plenty of those songs—but that does not work for our band. That’s not why our fans, at least, gravitate towards our band—I think there’s an inclusive nature to our songs that is why people like our band. They feel like we are writing something on behalf of them, we’re writing for them, we’re writing about them. It’s not, “This is about Brian’s life or Dave’s life.” It’s like, “They get my life, and they’re writing about me and my friends.” Every song may start as an introspective sort of thing, but it never ends that way. I went to great effort, actually, to tweak or evolve the songs so that it was grammatically plural and inclusive.

SYMONDS: That emphasis on inclusivity does make it easier for people like me to put you guys in this tradition—like, “They’re doing a Replacements, Springsteen, Hold Steady thing,” which gets said about you a lot. I don’t think you guys sound that much like Hold Steady. It’s much more about the idea of urgency.

KING: I’ve read that a lot, and I agree, because I don’t think that sonically, or the delivery of the songs and the types of songs, necessarily are quite so parallel to The Hold Steady. Especially lyrically and vocally, they have something that’s quite different from what we’re doing. I do think that they’re similar in the sense that—and I think you could say the same thing for bands like Springsteen and The Replacements—that music is for a certain time and place, and I think our music is also for that certain time and place.

If you like the Hold Steady, and you know about them, and you have them in your music collection, there’s a certain time of the day, or a certain part of the week—a time where you’re like, “I need to listen to the Hold Steady right now.” And I think our band serves a similar purpose. I don’t think, sonically, any of those bands actually sound like any other. But they all contain almost an unsaid feeling within the music that says, “This is the music for this moment. When I’m doing this, I need this. When I feel like this, I need this.” Knowing all those bands, I can say that I put those bands on at the same time that fans of our band put our band on.

SYMONDS: Have people talked to you about what that moment is for them?

KING: I mean, I think it’s a pretty personal and pretty unique, from listener to listener, kind of thing. But to be very, very general: I think when people are sad and they want to be happy, they listen to bands like those bands, including ourselves. Or perhaps the opposite, when people are already happy and they want to push it really to the limit, then they put on those same kind of bands. That type of music, that sentiment, that feeling you get when you put it on is just right for certain occasions in the day, or in your life.

PROWSE: It’s the same with any music fan, but for both of us, personally, there are a lot of albums out there that are very much tied to a specific time and place. Like, “I remember listening to this album over this summer, and whenever I think of that time I think of that album immediately.” A really humbling experience that we’ve had was touring on Post-Nothing, was having people come up to us and tell that story about Post-Nothing. Especially as the tour went on, people saying, “I listened to your album when it first came out and I listened to it every day for the summer of 2009. That was my album for that summer; that was my album for this time in my life.” When somebody tells you that, it’s a pretty amazing feeling, and very humbling.

SYMONDS: Do you think of this album as a summer album?

KING: You know, what’s really funny is you often read things about it being a summer album or the band being the kind of music for summer. I think if you actually read the lyrics, you’ll find that it’s not a summer record, actually, at all. Thematically and lyrically, it has way more to do with the opposite—the references are cold and wet and rainy. It’s just interesting to me that people always associate the album with summer, because I personally don’t at all.

SYMONDS: You worked with Jesse Gander—when you were recording, was there more push or more pull from him?

KING: I think there was more push, on both sides. We were much more aware when making this record that there was actually an audience to hear it, which we didn’t have when we did the first record. This was the first time we made a record that we knew someone was going to hear, and people were going to review it, and people were going to listen to it; and he knew that as well. On both sides, we were much, much more meticulous. Visions were narrowed, and we had a much more specific idea of what we wanted to accomplish. On both the band and Jesse’s side, it was really just much more attention to the smallest detail than ever before. And the battles were even more spectacular than they were the first time.

SYMONDS: To speak to details—on Post-Nothing, there’s more of a sense that these songs are the way they are because they needed to happen right this second.

KING: Yeah.

SYMONDS: And with this album, there’s more of a sense that they were kind of worked over, and they’re cleaner, but also more complicated. “Adrenaline Nightshift” is a pretty complex song in comparison to most of the songs on Post-Nothing. Did you feel more confident when you were recording this time?

KING: Yeah.

PROWSE: I think we were just much better musicians, and I think that’s a big part of why. Post-Nothing is a pretty sloppy effort. We didn’t have a lot of time to record it. We just cranked it out as quick as possible, because we were recording it ourselves on our own dime, and we wanted to do it as fast as possible, basically. This record, we had a bit more time to make sure every take was as strong as it possibly could be. And yeah, we just played a couple hundred shows since then.

SYMONDS: Working towards your 10,000 hours.

PROWSE: Yeah, you’re just going to be better at what you do. So we could kind of push ourselves a bit more too. We really tried to push ourselves as musicians, as singers, as songwriters as much as possible, and make the best album we felt we could.

KING: We have three records: We have No Singles, which is a compilation of all our early material, Post-Nothing, and Celebration Rock. And the one thing that all three of those records have in common is—

PROWSE: —they’ve done really badly.

SYMONDS: [laughs]

KING: Each record is the best that we could do at the time we made it with the resources we had to make it with. So if you see an evolution in those records, it’s that the best we can do now is not the same as the best we could do a few years ago, when we made Post-Nothing, which is not the same as the best we could do a few years before that when we made the songs that are on No Singles. I think we both feel that this is the best record we’ve ever made. And I feel like we thought that when we made Post-Nothing, as well. And if we couldn’t make a better record than Celebration Rock in a couple of years, I don’t think we’d make another record.

PROWSE: I think if you think of our lives as musicians, it’s craftsmanship. We’re not artists, we’re more artisans. You know, I don’t think we view ourselves as musical geniuses who can just make some sort of wonderfully beautiful record out of nothing. It’s something that we work at. And if we keep working, hopefully we’ll keep improving.

CELEBRATION ROCK IS OUT NOW. JAPANDROIDS WILL PLAY BOWERY BALLROOM TONIGHT AND THE MUSIC HALL OF WILLIAMSBURG TOMORROW.