show some respect

Issy Wood on How She Got to Know Mark Ronson During a Global Pandemic

I’m looking through my texts from late last year, when the world was normal, to find out when Mark Ronson and I were first put in touch. In November 2019, I’m introduced by our mutual friend Chloe, and Mark arranges to come to my studio the following week. The day before, I send him a panicked text from my therapist’s office saying that if he was in some way bribed or coerced by Chloe to feign interest in my “music hoby [sic]” then he really didn’t have to come over; he said no, accidentally tried to FaceTime me, apologised.

Mark hasn’t been to the shady end of Whitechapel before, so I give him a brief tour of the yard my studio is in: the drug dealer, the nursery, the call center that becomes a gospel church on Sundays, the accountant. We look at my paintings, talk, he suggests I self-release some demos, then leaves for a diabetes gala.

The overwhelming feeling I have over the next month about Mark, and the strange detour he represents, is that I somehow bypassed the “struggle” we’re told musicians are supposed to go through in their early years. Perhaps you play a family friend’s James Bond-themed bar mitzvah, or a gastropub where somebody was recently stabbed—you get booed, you mercilessly peddle yourself to no avail. Yet here I was with a cheat code, having Mark be the sixth person on the planet to hear the secret songs I make in my kitchen. It was—is—fantastic, and perfect gasoline to pour on the year-round forest fire that is my imposter syndrome.

At the beginning of December of last year, Mark tells me he has a gift, but that it’s stuck in customs. When it finally arrives, a LinnDrum drum machine from the 1980s, Mark has left London and I have to collect the enormous box from Chiltern Firehouse and wheel it home. I write Mark asking how the fuck I plug it in, which wires to use. The laminated label saying MARK RONSON on the machine’s base informs me this isn’t a gift, but a loan.

Learning to use the LinnDrum is painful. I sense Mark’s respect for me hangs in the balance and begin to resent him for lumbering me with such high existential stakes. An instructional YouTube video by a man called Doctor Mix helps. At the time I’d tried to make amends with my estranged father by inviting him for a session with me and my shrink. My dad used the hour to give a verbal PowerPoint presentation about how I’d failed him as a daughter, and it broke my heart. I text Mark three demos off the bat using the LinnDrum: “Out,” “Cortisone,” and “Cry / Fun,” the vocals for all of them made wobbly by intermittent sobbing.

Over the holidays I try constantly to draw parallels between art-world and music-world roles and dynamics; they collapse every time. Almost everybody I’ve met in music is a man, so I couldn’t, for instance, go to anybody at the label with my ever-expanding daddy issues and explain their part in my music to any great extent. In art, I work near-exclusively with women who want to know everything. What is a music producer like Mark, who doesn’t produce any of my music, in art world terms? A gallerist? A restoration specialist? A curator? An advisor? For me, he’s somewhere between a museum director and a kind collector, but that could change.

Shortly after New Year’s, Mark brings a guitar pedal and another drum machine to my apartment, asks if I’d like to sign with his label Zelig, and tells me I should hire a lawyer. We arrange a time to mix the tracks for my EP in February, and I google whether mixing is different from producing.

At a studio in Shoreditch over two days, Mark brutally cuts a verse and chorus from “Cry / Fun” while I eat a Niçoise salad. I decide music studios are oppressive, like airplanes. I bring him a copy of the book I made from two years of blog entries, and he says he intends to be extremely careful with what he tells me in future lest it end up published, which makes me feel like a tabloid journalist. After mixing the EP, we walk to hail cabs and he wishes me a good shabbos. I notice he is wearing very dainty shoes and worry he’ll be cold. I go home, exhausted, and make the song “Insist,” which includes the lyric “I’m not sure what I’m doing here.”

By spring, the pandemic we all thought wasn’t a pandemic is a pandemic, and I begin referencing “my lawyer” in conversation to scare people. I make more songs in lockdown, and send them to Mark. Physical affection in 2020 seems like more and more of an oxymoron and the music is getting more and more sophisticated every time I open my laptop. Mark is camped out just across town, but the restrictions make boroughs feel like separate planets. His distant approval, however, is like caffeine. I make more songs.

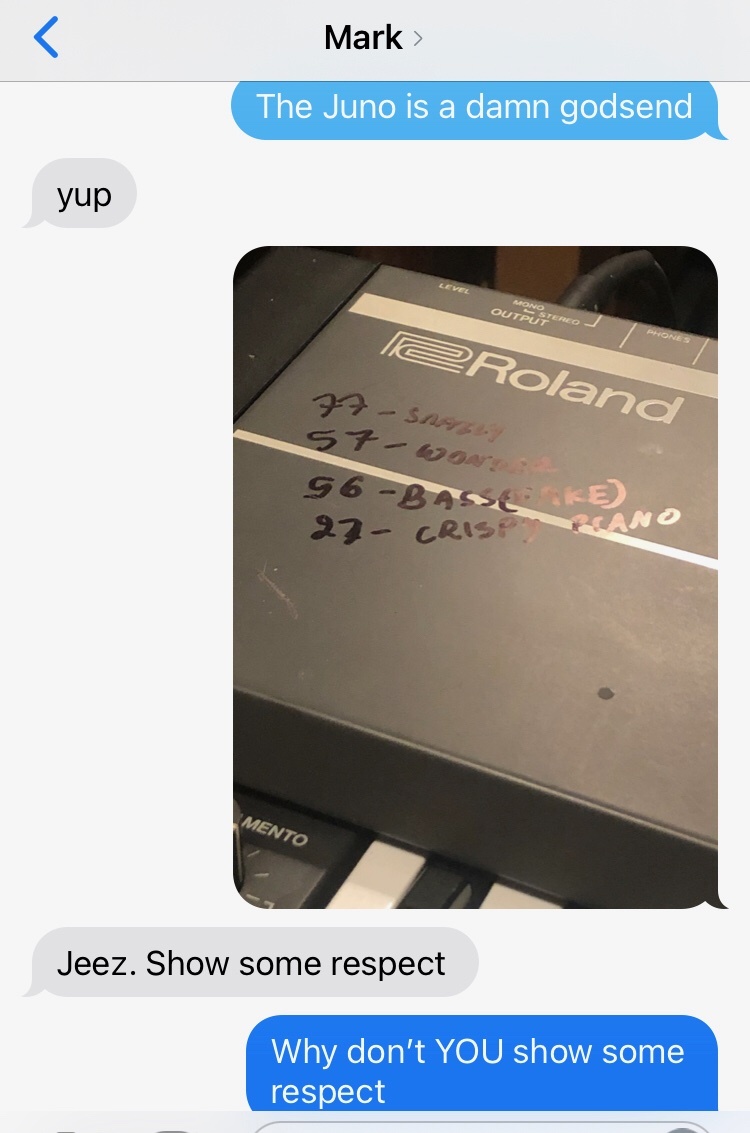

In the summer, Mark comes back to my studio, we listen to the new stuff on my fancy speakers, and he gives an occasional thumbs up to moments he likes. He hooks me up with a Juno-106 and says synth is the one thing missing from my kitchen orchestra. I endure the same teething problems with the Juno as I had with the LinnDrum, I play the keys like a Boomer typing on a Macbook, and the looming pressure of MARK RONSON stickers haunts my dreams. When COVID is calmer, Mark and I eat those vegan burgers that bleed at his house, and I have to correct several mistakes he’s made on Saturday’s New York Times crossword puzzle. It is the first time in our weird relationship that I feel more powerful than him, and I’m still dining out on that.

Issy Wood’s new EP Cries Real Tears! is out now