Exclusive Song Premiere and Interview: ‘I’m Gonna Die,’ Future Wife

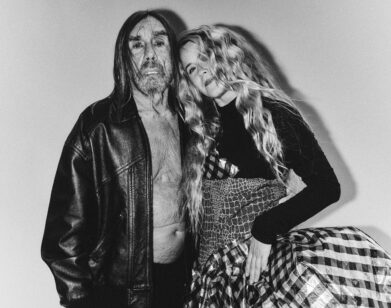

ABOVE: YOUNG JEAN LEE

Playwright Young Jean Lee was described last year by The New York Times as “hands down, the most adventurous downtown playwright of her generation”—a characterization confirmed by her cheerfully trekking uptown to conduct this interview. The Washington state native moved to New York City in 2002 intending to become a playwright, after spending five years at UC Berkeley working on a Ph.D. in English Literature, specializing in Shakespeare. Despite being a former academic and a noted writer, Lee is extremely open, direct, unpretentious, and funny.

With a diverse body of work, Lee has always created shows that test the boundaries of her audience’s comfort zone—and her own. She’s dealt, for example, with black identity (though she is Korean-American), with gender (performed by an all-nude cast in Untitled Feminist Show); and with her father’s terminal illness, in LEAR.

These days, she sings with her band Future Wife, whose first album, titled We’re Gonna Die, will be released on August 6. The album is composed of songs and a series of poignant but hilarious anecdotal monologues dealing with human failure, sickness, aging, and death; they were originally featured on stage during the world premiere at Joe’s Pub, which won her an OBIE Award. The show then moved to LCT3’s Claire Tow Theater at Lincoln Center, where it sold out after half an hour. On the album, Lee doesn’t do all the monologues herself—she’s recruited supporters like David Byrne, Laurie Anderson, Ad-Rock, Kathleen Hanna, Drew Daniel and Martin Schmidt (Matmos), Sarah Neufeld (Arcade Fire), and Colin Stetson to help out.

Opening to coincide with the album release, We’re Gonna Die returns to Lincoln Center on August 5 through the 17 (tickets go on sale in June). The live show will be directed by Paul Lazar and choreographed by Faye Driscoll.

GERRY VISCO: One of your trademarks is to try new things all the time. You’re a writer; now you’re singing! What other things have you done that you felt were challenging?

YOUNG JEAN LEE: I made a show that didn’t have any words in it. It was all movement… and I’m not a choreographer. With every show that I do, with every new project that I do, I really have no idea what the hell I’m doing.

VISCO: But that’s why it comes out well, I think.

LEE: I think so, in a way. Since I’m really so ignorant, I end up doing things nobody would do if they knew what they were doing.

VISCO: Have you always felt that you were very experimental, or was that something that happened later?

LEE: I feel like I’ve always been a weirdo. I look like an Asian girl, and there are all these stereotypes that go along with that. My town was all white. I always grew up with the sense of being a total outsider. I grew up so alienated from other people, and it never went away. It’s interesting, because I once got an email from a professor who was teaching a queer drama class, and he said that he was teaching my work because he felt that my plays were so queer. [He said,] “One of my students asked, ‘Is she actually queer?'” He said he was “still going to teach your work, but I just thought I would ask, and I assumed you were.” And I said, “Well, I don’t identify as queer.”

VISCO: It must be your sensibility.

LEE: I think so. I’ve had overweight people assume that I was overweight. I’ve always had this feeling. I’m so lucky to have found this world of downtown theater, which is the first place I’ve ever belonged in my entire life. In this world, I’m totally normal, but once I’m around people who are acting in that weird way that normal people act, then I become completely inappropriate.

VISCO: My theory is that the people who seem sane actually aren’t, because they’re trying to show everyone how sane they are. The so-called crazy people don’t care.

LEE: That’s how I feel! When I’m around “normal” people I behave around them as if they are crazy, which makes me seem crazy. Thank God I found this world, because if I hadn’t, I don’t know what would have happened to me. I really just never belonged anywhere.

VISCO: When you were in high school, did you feel alienated?

LEE: From early childhood through high school, I was so isolated. Super-shy and super-awkward; I was an only child; my parents were super-religious. I didn’t know how to behave in that world.

VISCO: What religion?

LEE: Evangelical Christian—totally hardcore. The missionary converted them. My dad passed away, but my mother’s still alive.

VISCO: Are you still close? How does she feel about your work?

LEE: I made one show for her. It was an Evangelical Christian church service called Church. It takes a weird turn into mummies and unicorns that totally confused her, but there was no swearing, no sex, nothing disturbing, so she was okay with it. She liked it. And then I showed her this other show called Songs of the Dragons Flying to Heaven which starts with a seven-minute video of me getting hit in the face repeatedly, and she was very, very traumatized by that; and so since then, she hasn’t seen any of my work. She watched We’re Gonna Die online, and she was traumatized because I tell the story of how my dad died.

VISCO: This is your first album. So your topic is death?

LEE: Yes. I did this show called We’re Gonna Die at Joe’s Pub, and then it remounted at Lincoln Center and it’s been touring. I made the show after my father died, and the whole point of the show is that isolation you feel when horrible things happen to you, how no one can ever be in there with what you’re experiencing. I made a show trying to comfort myself, and by extension trying to comfort other people who were in that situation. The show is monologues and songs, and so for the album I just got all of my musician friends to record the monologues for me instead of me doing it.

VISCO: How long have you been singing?

LEE: I sang when I was younger in choirs, but I was never really a “singer.” I had to take voice lessons for a year to prepare for this show. That’s sort of the point of the show: I’m not a glamorous Liza Minnelli type… The idea that I was standing up there—that I wasn’t a performer and I wasn’t a singer—was what made the show work… The whole point of the show is this thought that I was “special,” and should be exempt from all these horrible things. And then the realization that I wasn’t was really helpful. The main phrase that came to me was: “Who do you think you are?” Who do you think you are to be immune to tragedy? What makes you so special that you should go unscathed?” That was a huge turning point for me. It’s that anger that an injustice was done to you that really kills you. That rage can really eat you. It’s not an injustice; that’s what the world is.

VISCO: When did you start writing plays?

LEE: After I dropped out of grad school, during the past 10 years.

VISCO: Did your doctoral work give you some inspiration?

LEE: Absolutely! I spent 10 years studying Shakespeare. That’s completely informed how I approach theater.

VISCO: Had you always had some vision for your life and career?

LEE: No. Through most of high school I was this complete non-entity. I wasn’t good at school; I wasn’t good at anything. I don’t know how to describe it.

VISCO: You were boring?

LEE: I don’t think I was boring! I think I was a weirdo. I would read all the time, but externally, I had nothing to show for myself. I had a rich inner life. At a certain point in high school, I realized that if I don’t get out of Washington state, or the Northwest, I’m just going to be like this for the rest of my life, and I didn’t want that. So I did everything that I could to get into Berkeley. I really busted my ass to get in there and I got in. My father told me before I left: “You mother and I are gonna be really proud of you if you get C’s. Just pass!” I ended up graduating in the top 12 of my class; I was an academic star! It was my first time in my life ever being good at anything.

VISCO: Was it because you were more comfortable there?

LEE: I think it was because I loved theater… but I didn’t “know” that. I was not really cut out for academia, but I loved theater so much and my professors saw that passion. I was groomed for academia, and after 10 years I had a kind of nervous breakdown. I went to a therapist because I was almost suicidal. And she said, “I’m going to ask you a question. Don’t even think about the answer. What do you want to do with your life?” And I said, “I want to be a playwright.” I just left everything and moved to New York in 2002. Almost everybody in my life thought that I had gone completely insane!

VISCO: Have you ever thought about doing films?

LEE: I just made my first short film! It was the most fun thing I’ve ever done. It’s called Here Come the Girls. I feel like film might be more my medium, because I’m such a control freak. Film really enables you to control the final project… I wrote one film script, but it was kind of a disaster.

VISCO: Why?

LEE: It was for a major Hollywood studio, and it was so not the right fit. It was me being too much of a weirdo. Every time I try to fit into a more mainstream theme, it just never works. It’s not that I’m unwilling!

VISCO: I feel like your stuff could appeal to the mainstream eventually.

LEE: I don’t know about that. In terms of the downtown world, I’m not the biggest weirdo. There, I’m one of the more normal ones, which makes it seem like I could appeal to the mainstream. That’s the ultimate challenge for me: can I just do something normal that isn’t weird at all? Although this next play I’m doing, which is called Straight White Men, is my attempt to make something that is completely mainstream and normal, I don’t know if that will work for me.

VISCO: How will it be more mainstream?

LEE: There’ll be a story.

VISCO: Back to your new record, that’s part of the show.

LEE: There are six songs in the show. We were going to release just the EP, but we decided to add all the monologues from the show, so listeners can go see the show and get the record. We’re also making a music video at the beginning of June.

VISCO: What advice do you have for someone just starting out? You came to New York City not trained in the field, and you did it the hard way.

LEE: I made my first show for $200. Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals for the Ontological-Hysteric Theater. A difference that I see between myself and some of my peers is I have the gall to just keep asking for more from my performers and everyone around me. I keep pushing and pushing and pushing until I like what I’m seeing and that takes gall. People don’t like to do that. They like to be respectful, especially when you’re not paying someone. That’s how you wind up with mediocre stuff. That came up with this album. Everyone doing a monologue was substantially more famous than me, and they are doing these monologues for me as a favor, on their own time and emailing them to me. These people have insane schedules. I just kept asking them to do it again and again and again for free. It was so painful to ask.

VISCO: You thought that it could be better.

LEE: It was just that drive that this could be better. It was torture for me to ask David Byrne to keep doing it. Every time I’d send him an email, I wouldn’t be able to sleep. I gave him the cancer monologue about my father, which was the hardest and longest one. He’s the most down-to-earth, sweetest guy. I’m amazed at how far you can push people before they’ll say no. Don’t put stuff out there that you don’t feel 100% about. I wanted the album to be good so badly.

VISCO: How did you compose the songs?

LEE: I sang the songs into an iPhone and made a recording.

VISCO: What aspect of death do the songs deal with?

LEE: It’s everything. It’s heartbreak, it’s loneliness, it’s self-hatred, parental rejection, and every awful thing that an average person goes through. The only story that’s about me is the one about my father. They’re all true, but I made them as generic as possible.

VISCO: Was your father’s illness long-term?

LEE: Yes, he had advanced stage lung cancer for three years. The way that he died, at the end, was really horrible.

VISCO: Any words of wisdom for those of us who are going to die?

LEE: Once you take away the outrage and the anger that this shouldn’t happen to you, it really does help. I’m going to turn 39 this month, and one of my friends told me recently: “You’re on the last gasp of your youth.” For a while, I was really freaking out about it. But then, it really helped to think: there’s no reason why this shouldn’t happen to me. Aging and death is what happens to everybody.

FUTURE WIFE’S WE’RE GONNA DIE IS OUT AUGUST 6; YOUNG JEAN LEE’S SHOW BY THE SAME NAME RETURNS TO LINCOLN CENTER AUGUST 5.