Circlesquare’s Jeremy Shaw Won’t be Pegged

Photo of Jeremy Shaw by Zoe Bridgeman

As Jeremy Shaw took the stage at the Glastonbury Festival on Friday evening, “Back to the Future,” a group show including his work, opened at COMA gallery in Berlin. Shaw is not an artist/musician, emphasis on the “slash”—although he is both artist and musician, the latter in the form of Circlesquare, a one-man operation the Vancouver native has headed up since the late 1990s. Circlesquare, now based in Berlin, has just concluded an international tour, in its full live incarnation with Dale Butterfield and Trevor Larson, promoting its new album, “Songs About Dancing and Drugs”; meanwhile, this year Shaw has exhibited in Basel, London, Berlin and Vancouver. In a territorial art world that demands the constant assertion of one’s domain—in medium, in subject matter, or even geographically—Shaw commits the perfect crime: He’s a disciplinary two-timer, and the results speak to periphery culture and the art world with equal bearing. Plus, you can dance to it.

VICTORIA CAMBLIN: You’re not really focusing on art these days, are you?

JEREMY SHAW: I’m trying to! I have a huge public poster project I’m working on in Vancouver right now—every two weeks there’s a new poster, for the whole year. Vancouver has the Olympics next year, and in 1986 we had the World Expo 86. That’s two massive world events in the span of about 20 years. Of course, with the Expo there was a ton of political fallout… for instance with the McBarge, a floating McDonalds on a barge. After the fair ended, the McBarge was this monstrosity that sat there for ten years while people fought about what was to be done with it. Now it’s docked, inland just out of view of the city—a distopian 80s relic. So the original idea for the project was to do a poster that looks like an Ansel Adams photo, with a beautiful Pacific Northwest background, but with the McBarge obstructing the view.

VC: Is the McBarge still operational?

JS: No, but they did shoot Blade 3 on it—it was the vampires’ hideout! So the project was going to be a critical response to the city of Vancouver building new buildings for one-off Olympic events— speed-skating rinks, for example. I received funding from the Olympics for the poster project, although I’m sure they’re going to pull their name off it soon. The project evolved into more than just a document of the architecture to include archival ephemera from the fair, and promotional items. I found my mom’s season pass from Expo with her photo on it and made a poster out of it: She’s going to freak.

Circlesquare – Dancers from Bienvenido Cruz on Vimeo.

VC: Does she look good?

JS: Well, she looks 20 years younger! But halfway through, the project will shift. There was a small riot at this thing called the Festival of Independent Recording Artists, where they had local bands slotted to play. A punk band called Slow opened, and they were shut off during their set because patrons were complaining, so the singer stripped down totally naked—with an erection—and started shouting, “Sieg heil Bill Bennet,” who was premiere of the province at the time. It started a minor riot where the kids marched down to the local TV station that was broadcasting the news live from the fair and made such a racket behind the anchors that they had to pre-empt it.

VC: You were quite young for the event to have made such an impression.

JS: The event was mythologized in Canadian punk rock history. I was only nine at the time, but I managed to track down the only known person with photos. Finding them was the turning point in the project, where things go from the shiny, slogan-driven, “See what your world is coming to in 1986” booterism-type posters, to images and ephemera relating to the social unrest sparked by things like low-rent housing evictions and said massive, single-purpose structure building. Instead, you ee a guy from behind, exposing his dick to the crowd. (POSTER, 2004)

VC: These mythic music moments seem to tie into your work at large, in that you’re dealing with collective, and at times transcendental experience…

JS: That’s always been a theme: group mentality and the psychedelic, altered states. Lately I’ve been working with brain scans, MRI scans, as scientific representations of altered states. I think of them also as kitsch or populist representations. I guess I’m trying to elevate that kitsch, in a sense —juxtaposing the average drug user’s or altered state enthusiast’s attempt at representing their experience, with the equivalent experience’s representation in advanced science.

VC: Doesn’t one risk being seen as “retro” dealing with these kinds of topics?

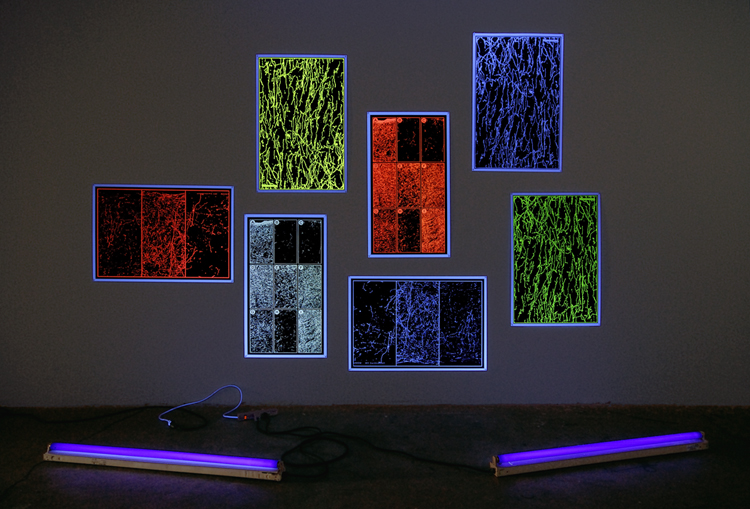

JS: Aesthetically it might seem that way. “Psychedelic” is such a problematic term because by cultural definition, it encompasses everything from fashion to guitar sounds. Whereas to me, a truly psychedelic experience should be something that’s foreign, something alien. In one work (Representative Measurements of Altered States, 2008) I took microscopic photos of brain tissue showing a comparative study of serotonin levels in MDMA users and control subjects, and made classic “head shop” style black-light posters out of them.They’re instantly recognizable retro/kitsch objects that are used to aid drug experiences—but the images themselves are actually representations of high scientific data attempting to illustrate the effects of said experience on the brain. With a piece like DMT (2004), I completely eliminated the kitsch or retro factor by videotaping people having a hyper-psychedelic experience in a white, clinical setting—totally devoid of the immersive visual effects typically associated with psychedelia.

VC: Hence the “Songs about dancing and drugs” theme on your newest album, dancing and drugs being the two traditional methods of transcendental experience?

JS: Well, they’re the most common, after religion, maybe. It’s funny because the music and art do overlap in my thinking, topically, but I never call the music art, I never refer to a Circlesquare show as a “performance.” It’s all “art” to me, but a lot of times when artists make music it tends to be glib. Artists will have their token punk band but it’s not supposed be taken seriously like their visual practice.

VC: It’s dangerous, no? To cross over?

Representative Measurements of Altered States (to Aid in Further Alterations)

JS: It can certainly complicate things. I often have to downplay the music to art people, and the second music critics hear that you make art it changes the way they hear the music. I swear they think, “He thinks he’s too smart,” and color the reviews accordingly. It’s a weird thing that the two don’t involve each other more; they inform each other and borrow from each other so much, but generally don’t like to mingle.

VC: But your art and music strike me as pretty coherent.

JS: They’re just two different parts of my practice. I try to not over-analyze the music side. It’s far more expressive—more like painting, in a way. I can get very geeky on the production side of music, but with art I’m attacking it from a much different, often much more didactic way. But has there been someone who’s really successfully done both art and music? At least in terms of a pop capability?

VC: Well with some musicians, their music is already so appealing to artists that making art seems superfluous….

JS: I mean, I generally feel the same way! I think the problem is the audience’s capacity to move forward with you, or at least to want to know that much about what you do creatively. One aspect of the arts is enough, which is fine really, so long as people don’t discredit them both for the fact that you do both. Take someone like Mike Kelley, Rodney Graham, Yoko Ono—they’ve always made music.

VC: I hear Marilyn Manson’s paintings fetch a pretty penny…

JS: Well, I’m not big enough in either art or music for my work in one discipline to sell the other! Which is good, I think. I don’t want people to say, “You like his music, you should see his art.” Because I don’t think it’s necessarily the case that people would like both. I also don’t think you need one to understand the other. I do though, in both fields, strive for a pop sensibility, and a wide appeal.

VC: Perhaps it’s a bit cliché, but the high/low juxtaposition really works!

JS: I love that though. This could just be my own Catholic guilt, but even when my early work was all skateboarding and hardcore and rave culture-based, I felt this real sort of debt to the subjects, rather than just wanting to tip the art world off to a scene. I always had this idea that the people that it was about had to respond equally if not more than the art public—it’s just too easy to sell something underground to the art world… not to mention crass.

VC: I’m convinced that the most provocative, or the most irritating-in-a-good-way things are not happening in the underground anymore, but in the mainstream. Like Kanye West making some insane fluorescent Africana video à la Grace Jones.

JS: Totally. As much as he seems to be forcing things, I still think it’s quite subversive, especially considering the major market that he still hits regardless of how ‘arty’ he gets and who’s tipping him off to it. And, though this hasn’t been the case for people like Kanye, if you can break into the pop world using the exact tropes that are always found there while still doing something underground, how much more subversive can you get? Take Daft Punk: When they went number one in America, that was still underground dance music being copied by hundreds of house artists. It still is being appropriated—see Kanye.

VC: And you’re not really asking people to look at your art and music at the same time. Jeremy Shaw makes art; Circlesquare makes music.

JS: No, not at all – I’m totally fine keeping them apart. I guess another thing with me is that with music, I’m trying to work in the pop structure of the industry. It may be challenging pop, but I’m doing proper videos and press and touring and that kind of thing.

VC: Your videos even have choreography!

JS: I’m totally going for that right now. Again, I think it’s really challenging, to use these cliché pop structures as such. You can trick people. You can really lure them in with a little fancy dancing …