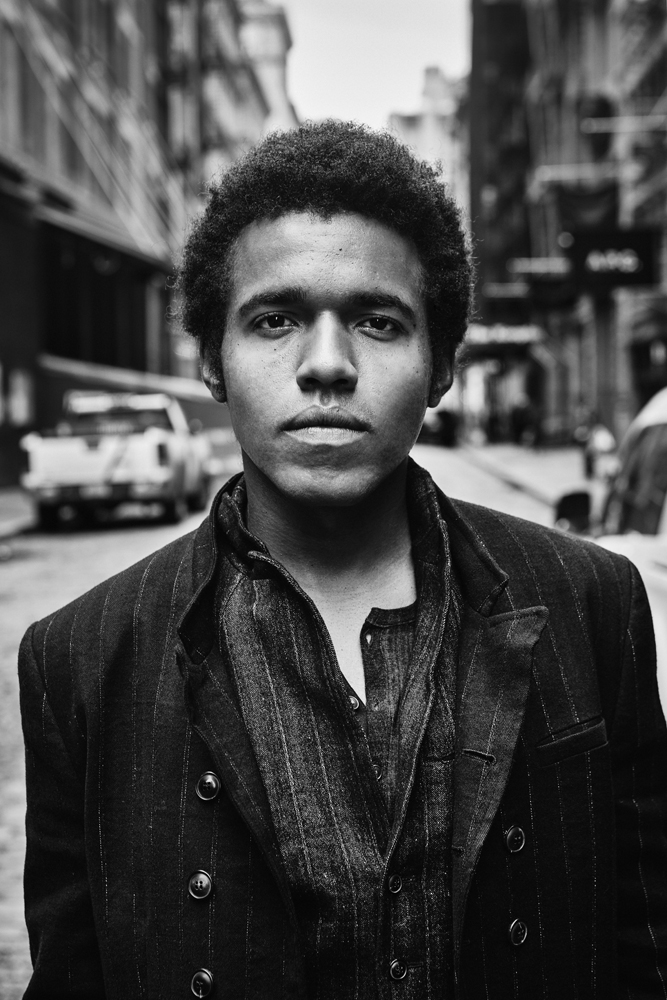

Benjamin Booker

When we ask Benjamin Booker what he’s reading during his recent trip to New York, the 28-year-old musician jumps up, grabs his leather bag, and digs into it. He pulls out two paperbacks: The Moviegoer, a novel about New Orleans, the city he lived in when he first became a musician, took up the last name Booker, and wrote his eponymous debut album; and Jean-Paul Sartre’s Existentialism and Human Emotions, which he jokingly describes as “some light reading.” These books speak to Booker’s train of thought over the past year and a half. He’s been reflecting on where he was in Louisiana, working for AmeriCorps with little money and some damaging habits, and his youth in Florida as a punk-loving skater. He’s also been trying to be more present; in understanding what’s formed him, he can shift his values, and, perhaps, be happy. This outlook developed after Booker left New Orleans, following the release of his first LP in 2014 and subsequent months spent touring, when he took a trip to Mexico to gain some distance.

“Part of the reason I went down was to take myself away from the people that I knew, my home, the comforts, and try and see who I was without the things that I had known forever, which is rough,” explains Booker. “I guess you realize that those are the things that make you who you are.”

If Booker’s first album was about his surroundings and problems with those around him, his second, Witness (ATO Records), released earlier this month, is a personal offering in which he admits, as he puts it, “I’m not perfect.” In a style that reaches from rock ‘n’ roll to gospel, he discovers what’s within his reach and what he has to change in life. This awareness also sees him look beyond himself and pose questions. On the record’s title track, featuring Mavis Staples, he asks, “Am I going to be a witness?” and questions if that role, amid repeated hate crimes against black Americans, is even adequate.

Booker, who’s been based in Los Angeles since his trip to Mexico, seems to be settled, at least for now. He begins a string of U.S. dates next month, which will take him across the country through the fall.

HALEY WEISS: We have something in common: I’m also a Floridian. They have a really big punk scene in Gainesville, right?

BENJAMIN BOOKER: That’s the whole reason I went to school [at the University of Florida]. I didn’t even really apply to any other schools, because if you’re a kid growing up in Florida who’s into punk, that’s the mecca, which is two hours away from where I grew up [in Tampa].

WEISS: I maybe project this onto other people, but did you have that desire of “I need to get out of the state of Florida”?

BOOKER: Oh my god, yeah. Immediately. As soon as I finished college, I think a few weeks after, I left to New Orleans. I just bought a record from Gainesville that I found of punk bands—it’s from the ’80s—and it’s called We Can’t Help It If We’re From Florida. I think everybody that grows up there, you’ve got a little chip on your shoulder. It’s not as bad as people think it is, but it’s pretty bad. When you go to other places you’re just like, “Oh, god. What was that about?” [laughs] It’s just us and New Jersey, trying to keep it together.

WEISS: You’ve talked a lot about your debut, the difficult time in your life it emerged from, so I’m curious what your mindset was going into this album: what you were thinking about, what you were reading, what you were listening to.

BOOKER: Going into it, and one of the reasons I left the city and went to Mexico, is that I was in a very unstable, chaotic time. Coming back from the last album, I just hadn’t found my back-home swing. You’re gone for two years or so, and then you’re home and you have nothing to do. There’s nobody, no job. Every day you can do what you want, which I guess is a freeing thing, but after a while it feels like a prison. That’s the headspace I was in. I had to figure out what I wanted, I guess, in life, what I wanted to do—if I wanted to keep making music, or if I wanted to do something else.

WEISS: Did you take time off where you didn’t make music?

BOOKER: I couldn’t write music at that time. You have to have some kind of clarity or understanding of what’s happening to write, I think, and my head was in so many places, all over the place, that I couldn’t if I wanted to—that’s why I left. The month being gone was a time where I didn’t speak the language at all, so it was just me, isolated, by myself, literally a month of being able to clear my head.

WEISS: Why’d you choose Mexico City?

BOOKER: It’s cheap. I had a few friends that I met the year before at a festival, and so I knew I had some people to show me around if I needed it, and I really liked it when I went there. It’s one of my favorite cities. When I left [to go there], I didn’t know if I was going to come back.

WEISS: When you got back to writing and making, did you have a specific goal or approach in mind?

BOOKER: I wrote the whole thing in Mexico. I didn’t go, “I’m going to go to Mexico and write this album.” It wasn’t like that. I was reading this book on the plane ride over there, and there was a [Don DeLillo] quote that said, “What we are reluctant to touch often seems the very fabric of our salvation.” I realized that the reason why my head was so cluttered and why I was so unstable and not taking care of myself, all of these things, was that I was unhappy. If I wanted to get to a happier place and find some kind of peace, I was going to have to address problems with myself, things from my life up until that point that I hadn’t dealt with—insecurities, fears, and those kinds of things. [pauses] You know in psychology they have Maslow’s hierarchy of needs? At that point, I was doing okay, so I was confused because my basic needs were taken care of. I could pay rent, I was living comfortably, but I still wasn’t happy. The highest point of that—everybody’s looking for that peace, that happiness, the self-actualization at the top of the pyramid—I was stuck. But I think that’s what I needed to do, to address those things that I didn’t want to talk about.

WEISS: So you addressed that through the music?

BOOKER: That’s what the album is. When I read that, I took out a piece of paper, and I wrote down all of those things, the things that people lie about—you lie to yourself about who you are—and I wanted to be honest about the person that I was. It seems like a very simple idea that you are the sum of your actions, but people, I think, have a hard time really grasping that and thinking about that. It’s not enough to have good intentions. If you want to be a good person, you have to make good decisions all the time and live a life that’s worth living and that you can be proud of, and that’s what I wanted. I wasn’t at that point when I was going to Mexico, so I was trying to get there. I wrote that list down and those things became the basis of the album. It’s like an outline for me of how I can live a better life, trying to break away from the bullshit.

Part of the process in deciding the person that I wanted to be was, “Okay, if you’re to do music, do you just want to be an entertainer? Do you just want to write songs about girls and those kinds of things?” I thought about being older, and looking back on that, and I didn’t think that I would be happy doing that. It was important for me to go even more personal on this album and share this experience of what I was going through because it has helped me. I think part of making the album was to show people the importance of self-reflection and always trying to improve yourself, and to know that you’re not finished. You will never have the answers, but you have to keep pushing yourself and keep reading and keep working on yourself.

WEISS: This is one of the most existential, broad questions I’ve probably ever asked—

BOOKER: [laughs] I was going through an existential crisis.

WEISS: So it’s appropriate. Do you feel like you know what you want out of life?

BOOKER: I really think that I do. Obviously that could change. I wrote a song for Mavis Staples’ last record, and when I was talking to her—it’s nice to talk to older people—she was so positive and so happy, and the only thing that she was focused on was being present and spending time with her family and her friends. I guess when you’re younger that sounds so boring, [laughs] but that’s where I am now, that is what I want. I hope that I can make music that helps people in some way or that they can connect with, and that I can just live a life where I’m surrounded by people that I love.

WEISS: Does Los Angeles feel like home now?

BOOKER: It feels pretty good. Life is short, so I am one of those people—and luckily my girlfriend is too—who wants to live everywhere. I don’t know how long I’ll be there, but I like it right now. Part of the move was I needed to get out of New Orleans. It’s easy to be self-destructive, I think, in a town like that. I’m living a lot healthier than I was; I’m taking better care of myself now. I feel like talking about all of this, it sounds like I’m reading a lot of self-help books.

WEISS: No, it sounds like you’re in a really good place.

BOOKER: I am, but it’s not very rock ‘n’ roll. It’s like, “Hey guys, love each other and take care.” [laughs]

WEISS: That kind of rock ‘n’ roll is overrated. The struggling artist myth is not healthy.

BOOKER: I know. I don’t have any interest in that anymore. I guess that’s what I realized: I have no interest in living that life. The people that I grew up listening to, it’s like, “Oh my god, these people were dead by the time they were my age.” I think it gets romanticized, that kind of lifestyle. Those people were not happy, and I want to be happy.

I was struggling when I made this album, so it’s hard to think about what I will do next time. If I am in a good space, I don’t want to write. I go months without playing guitar or doing anything. I don’t even touch the guitar. Usually it’s not until I have a problem that I’m strumming; it’s not a thinking thing, you just feel the need to get it out.

WEISS: Do you ever go back to Florida, and if so, how does it feel to go back?

BOOKER: I hardly ever go back to Florida. It’s really hard to go back. I mean, I hated it so much. I didn’t grow up in a great neighborhood, and it puts me back in that feeling of, “I want to get out immediately.” That was kind of the push and what still pushes me, that I don’t want to end up back there. It doesn’t influence really the writing process, but afterwards, the work, I’ll play all the shows, I’ll do [it all]—I just don’t want to go back to that.

Part of what’s happened during this process is learning to accept those things, even things I didn’t like and I hated, because that is you, that’s part of you. I’ve seen it many times, there’s a Bob Dylan documentary called No Direction Home: Bob Dylan, and he talks about how he felt like he was born to the wrong parents and in the wrong town and how he had no connection to the place that he was from. That’s how I always felt when I was younger and why I think I connected to him so much when I was a kid. But I don’t think that that’s healthy. You can’t just make it up, and that’s what I was doing, slowly over time. Booker isn’t my last name. I realized I was becoming this other person that wasn’t me, and I wasn’t connected to the person I was. On this album, and through making this album, I have a better sense of who I am now, and I’m not angry about the past. I can’t listen to the first album anymore. I hear somebody who’s so confused and so angry about everything. That’s why the music sounded like that and why I couldn’t do it this time. I couldn’t make that kind of music. I’m not angry anymore.

WITNESS (ATO RECORDS) IS OUT NOW. FOR MORE ON BENJAMIN BOOKER AND HIS UPCOMING TOUR, VISIT HIS WEBSITE.