IN CONVERSATION

ANOHNI and Björk Talk Soul Music, Lou Reed, and Climate Collapse

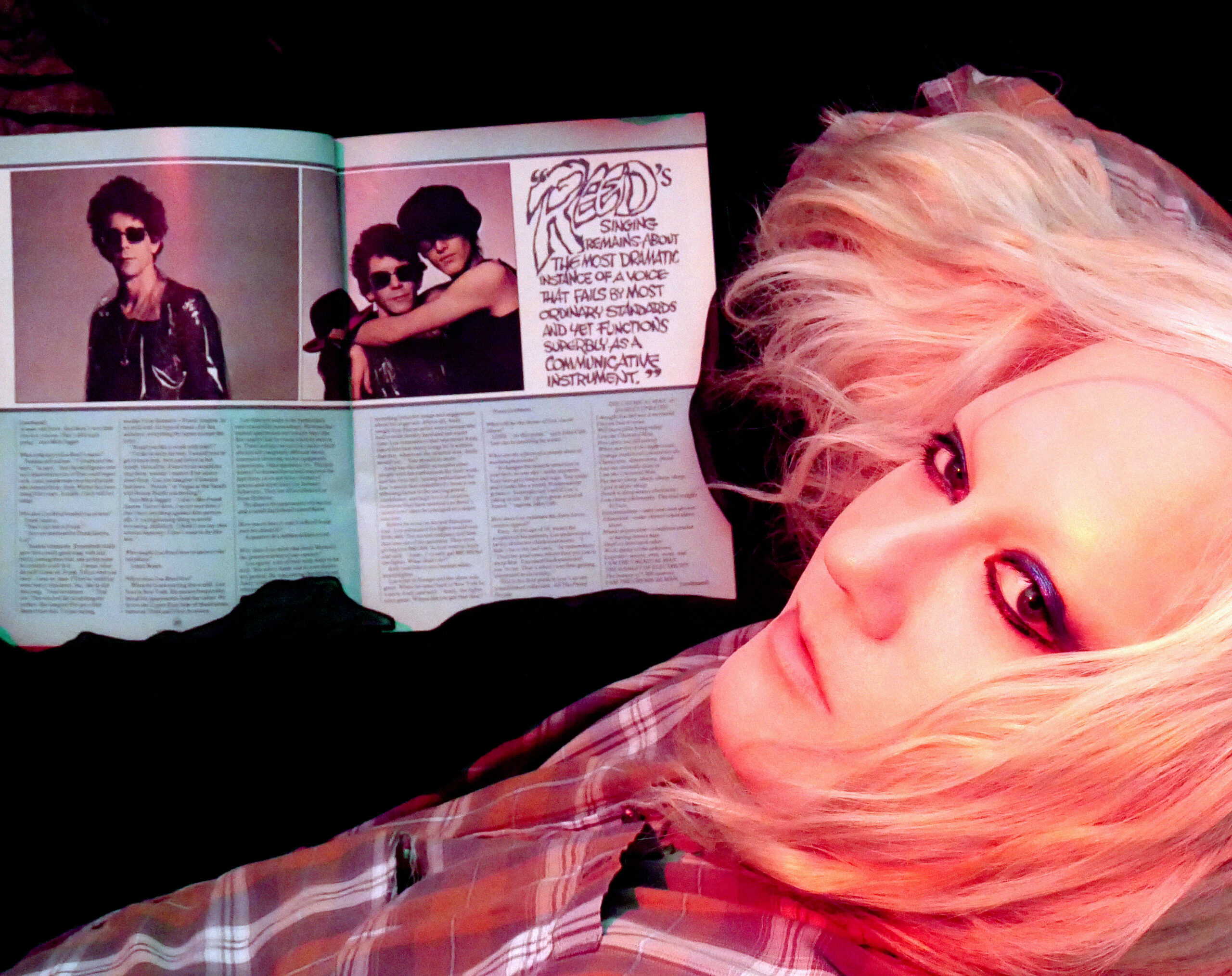

Photo by ANOHNI with Nomi Ruiz; photo of Lou Reed and Rachel Humphreys by Mick Rock. Copyright: The Estate of Mick Rock.

“To some people, we are also extremists,” quipped Björk to fellow trailblazing alt-pop musician ANOHNI when they got together earlier this month. As the pair traded theories about climate apocalypse and the “starvation of femaleness,” it became apparent why the collaborators-turned-friends share a cult following. Last week, less than a year after Bjork descended from utopia to sink her feet into the earth with Fossora, Anohni and the Johnsons released My Back Was a Bridge For You to Cross, her fifth studio album to date and first in six years. The soulful opus, which tracks environmental sorrow and personal loss, couldn’t be more evocative in a time of record temperatures and ominous orange skies. Over ten tracks unexpectedly heartened by the sounds of Motown, Anohni pays tribute to the legacy of activist music and builds trembling tension into an overflow of rage toward capitalism, ecological devastation, and systems of oppression. When her longtime supporter Björk called her up to discuss the album, she had a lot to say about her nostalgic connection to Black American soul music and the worldview that makes her music so poignant. Also: whaling, Obama, Lou Reed, and the first record she ever bought.—MEKALA RAJAGOPAL

———

ANOHNI: Shall we look at each other?

BJÖRK: I actually don’t have a camera in my computer. It’s broken, and let’s just say that I have not been in a hurry to fix it.

ANOHNI: Where are you right now?

BJÖRK: I’m in my house on the beach, and we had a sunny day today. It’s been cloudy for a whole month, so the whole nation is topless in the sun eating ice cream.

ANOHNI: I’m sorry to hold you from that activity. You’re taking a rest from touring?

BJÖRK: Yeah. It was quite a lot. In six months, I did South America, Australia, Japan, and L.A., so I’m really happy to be back home now.

ANOHNI: The photos from them were just crazy. The new cycle of looks is so unbelievable.

BJÖRK: Thank you. But I prepared proper questions. Do you think you can handle it? [Laughs]

ANOHNI: Yeah, I can take it. Thank you for doing this.

BJÖRK: I enjoyed trying to find another angle on our friendship to ask things that I haven’t asked you. I truly love your album [My Back Was a Bridge for You to Cross]. Your voice has never sounded that phenomenal and free, and you are singing with technique and colors I’ve never heard you do before. A true victory, one of the best albums ever. I’m curious how you maintain your voice.

ANOHNI: First, you’ve always seen me and supported me, so thank you. I don’t have any program for wellness around my voice. I actually hadn’t sung for several years. We were writing and recording the songs at the same time, which is something I’ve never done before. I’m that person where, if a song’s jumping out, it’s almost none of my business. The voice is doing what it wants to do. And later on, I go in trying to understand what that was. The joy of recording a song as I’m writing is that you catch that maiden emotional clarity. But I’m super intuitive, and I’m not very well-structured. I don’t have a particularly athletic process. It’s completely watery. I don’t know if I could even sing this record. We did the songs one at a time, so my voice was pretty fresh each day. It was a wholesome process for me, lonely as it sometimes was.

BJÖRK: I can really hear it, somehow. My favorite song on the album is “There Wasn’t Enough,” where you’re singing from the point of view of the earth, surprised about the ingratitude of humans and why you weren’t enough for them. I can’t stop crying when I listen to that song. The angle is so original and the falsetto voice is mind-blowingly effective. There’s also a comic ‘70s tone in “My Fault.” How do you change your tone of voice for different roles on this album?

ANOHNI: It’s often unconscious depending on the emotional register the song’s coming from. That weird, throbbing sound started coming from me in the late ’90s, and it tends to come up in songs where there’s a slow, still, untenable mourning.

BJÖRK: Like slowly rocking yourself to calm down.

ANOHNI: Yeah. And “My Fault” is kind of ridiculous, but it’s lighthearted. It’s like a bit of a sorbet between songs, but also using a gentle touch to say something terrible. That’s what this record’s been about for me. The last record was so full-on combative and self-eviscerating in certain ways. This record’s been an effort to find different ways to approach some of the same material with more tenderness, even as I’m addressing issues of complicity as a consumer or as a Eurocentric, “first world” beneficiary of the worst kind of depletion. It’s trying to work with that material while having a softer hand.

BJÖRK: “There Wasn’t Enough” was just so well-sung in that falsetto. How your voice breaks is just phenomenal.

ANOHNI: I’ve not really done a song like that. You’ve explored a broader range of sound-making than I have. I remember when I did “The Crying Light,” and you were like, “I like the way the microphone is purring.” It’s funny because your vision of that song is so beautiful and when I first wrote it, I was seeing it as though I actually wasn’t enough for someone else while I was holding space for nature. I wasn’t able to support a relationship when my body was betrothed to this other story.

BJÖRK: It has that openness to it.

ANOHNI: Hopelessness was probably the most strategically-designed record I ever made. It was designed as an intervention.

BJÖRK: It’s important for a singer-songwriter to work out how they can be a different character for each album and your character for this new album so beautifully owns the fact that we are all complicit in polluting the earth and then joining in the cure. This binary black and white thinking isn’t possible any more. I felt that way after #MeToo, you have to both see the point of the oppressor and the oppressed, and allow yourself to be more ambiguous. And sometimes the solution is to understand that we are all part of the same system and we all have to change. How do you feel about that message in your music?

ANOHNI: The feedback I got from Hopelessness was that people already felt the same way I did, and to them those songs were a source of solace and fortification. An artist came up to me after hearing “Drone Bomb Me” and was like, “It helped me to hear you use those words and sing in that way.” And I realized that it had empowered people who I really respected to keep doing their work and have a tangible impact. And a lot has changed. I did Hopelessness during Obama, and I felt there was much more room for me to make that record than under Trump.

BJÖRK: I mean, to some people, we are also extremists. I tried to address this in my song “Atopos” about how differences can be excuses to not connect. When you go too radically literal in wanting to heal the world, you can sometimes block connections. At the end of the day, we are all the same. I’m kind of tiptoeing between two stances, the critical one or the compassionate one. I was recently part of a whaling protest here in Iceland. We actually won a milestone victory yesterday.

ANOHNI: I saw that.

BJÖRK: Whaling got banned. And I found it hard to know what emotional tone to take. Once you spend your day grilling whale killers, you’re left with that energy. When you brush your teeth that evening, it is all mirrored back at you. So how do you find a balance?

ANOHNI: As things got hotter in America after the Obama administration, it seemed to me that I would be better off encouraging a tone of self-forgiveness or mercy in one’s exploration of one’s own complicity. To fall into despair or blame or denial isn’t productive. That’s been the development for me.

BJÖRK: That’s very consistent to the mood I felt when I listened to your album for a couple of days. Maybe it’s the reason my eyes kept filling with tears. It’s so sublime to take that stance because it’s not simple. Like you talk about in the first song on the album, there is a spark inside the darkness, so it is more complex. It’s tempting to make things black and white in a song, but I take my hat off to you that you manage to document that ambiguity and humanness.

ANOHNI: I try to use my body as a canvas to have these conversations. I’ve been thinking a lot about the network of brokenness that’s led us to where we are today and the collapse of the biosphere. You can throw so many different spanners at it to find a root cause, but I saw this research a couple of years ago that said that the genome of the grandchildren of Holocaust survivors had changed in detectable ways. So there was a physical marker of trauma that they carried with them. We carry generations of experience in our bodies, which is something that we’ve sought to dismantle, especially over the last century as we’ve forgotten from whom we descend and our longer relationship to the biosphere in order to be more compliant as consumers.. We need to not know what we’re eating in order to be comfortable swallowing it. I feel like there’s three legs of human perception—feeling, intuition and thinking. For the last two thousand years, feeling and intuition have been grounds for exclusion from any conversation of reason. The only thing that matters is this fake, rational, supposedly secular way of perceiving the world, stripped of all archetypally female skillsets. And that starvation of femaleness is so ancient for white people in Europe. It’s like a cancer that’s sublimated into the resignation that the environment is collapsing. We’ve gone from a society that was willing to accept the disinformation that encouraged climate denial to a society that is, for the most part, resigned to its inevitability. Is this really just reason at work? There’s a more powerful undertow. I think it’s also deeply embedded into our unconscious as descendants of Christians that we are supposed to climax in apocalypse.

BJÖRK: You’re describing my feelings very well. Coming from Iceland, I think somehow we managed to avoid a lot of that. We haven’t had a war for 800 years. We don’t have an army, and our spirituality is more connected to nature than religion. I’m not washing our hands of violence or anything, but it’s hard to even understand the psychology in the States, with two mass murders a day. We have almost no crime in Iceland but then again, we are all becoming one nation in the globalism today, so it’s not like we can point fingers at the USA anymore. I know it might sound naive, but we should be spending a lot of time in nature and trying to create a new narrative. There are a lot of environmental tasks—the acidity of the ocean, starting seaweed farms, salmon farming. But this apocalyptic story in USA can be very self-important in a way because they want everybody else to go through it with them. They act like it’s the story of all nations but it’s not. It’s exhausting.

ANOHNI: Well, it’s like a very powerful dream, and it’s been reinforced with a lot of violence over millennia. Obviously, everyone has to account for themselves individually. But the undertow of it is much deeper than any one person. It’s a survival strategy. Women who’ve been burned for centuries are going to stay in line more consistently than a feral woman who has never questioned her agency. It’s funny because I was looking at some of the lyrics on one of your songs [“Ancestress”]: “You see with your own eyes but hear with your mother’s. There’s a fear of being absorbed by the other.” When we did Future Feminism, Kembra [Pfahler] was always talking about the fear of being absorbed. She’d read a book that theorized that men had a primal fear of drowning in menstrual blood, drowning in femaleness, and that elicited a panic. That’s armchair psychology for an archetype. But as an idea, I found it compelling. And there’s examples of cultures that don’t require the crushing of femaleness to make decisions.

BJÖRK: I’m with you. Can I ask a cheeky question?

ANOHNI: Go on then.

BJÖRK: Is “Sliver of Ice” inspired by whiskey? The lyrics seem to celebrate the celestial angle of intoxication.

ANOHNI: Oh, god. That’s a very different interpretation.

BJÖRK: Prove me wrong.

ANOHNI: I mean, it definitely could be. You mean, “Now that I’m almost gone,” like shitfaced? I was definitely having a little tipple in those evenings. That song mostly came from stuff that Lou Reed said to me before he died, actually. His carer put a piece of ice on his tongue, and he called me up having these ecstatic physical experiences. He was just getting more and more grateful for the feeling of being alive, and it was inspiring. So I wrote it with him in mind.

BJÖRK: Sorry.

ANOHNI: But I like your interpretation. It’s a lot more hearty.

BJÖRK: It’s such a beautiful song. It really grows. Could you discuss “Why Am I Alive Now?” and your Marvin Gaye connection? It’s hard to imagine, but Marvin Gaye albums didn’t really reach me till I was 25. I’m kind of grateful I didn’t know what Motown was because it probably would have affected my music and I would’ve been soul-swamped. But I also understand that you put on the costume of retro ’70s soul folk to aid your message. It is the sugar on the bitter pill.

ANOHNI: “Why Am I Alive Now?” is closer to home because I was raised listening to generations of English singers who were inspired by Black American soul music. The new wave singers of the early ’80s were all singing in American accents with beautiful textured voices of people that should have been 30 years older. I’ll never forget Boy George singing “Do You Really Want to Hurt Me.” It was uncanny to hear this sound coming out of an Irish 20-year-old queen from the south of London. That transfer of musical and spiritual technology had such a seismic effect on all the music that was to come. So much popular music of the second-half of the 20th century was so deeply indebted

to the music of America during the civil rights era. I learned to sing by listening to Alison Moyet and Boy George and Annie Lennox. I was 10 years old listening to those singers and feeling feelings in my chest that I’d never felt before. It was like a saving balm to hear emotion being expressed so ecstatically. You wouldn’t have found that in Greensleeves or English folk. But the technology came from somewhere. You said that it would’ve ruined you, but honestly, it saved me. And it embodied a certain resilience. It gave me a roadmap for how to feel in a world in which I felt alienated; it recognized my heart in a life-saving way. It told me that I had to sing. So as I got older and moved to America, I started to understand the source material for a lot of that singing, all those generations of iconic soul singers.

Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On was the first record I’d ever heard that went topically, song by song, identifying issues that accumulated into a concise worldview using direct language to talk about what was really happening. And it wasn’t veiled. The messages weren’t sublimated into love songs. It was a very clear and direct cry for the environment in 1971. Now, environmentalists look back on 1971 as a biodiverse paradise. David Attenborough describes 1971 as a spectral oasis of riches. But there were artists that were already saying, “Radiation underground and in the sky. Animals and birds who lived nearby are dying. What about this overcrowded land? How much more abuse from man can she stand?” There’s a precedent in civil rights music for these kinds of truth-telling. By including environmentalism, Gaye created an intersectional conversation about the systems that were creating conditions for a broader collapse. And here we are 50 years later, so I wanted to really call out to that record, “Mercy Mercy Me.”

BJÖRK: I just discovered recently that it is an environmental song. It’s kind of mind-blowing.

ANOHNI: It’s an astonishing song. It could have been written today. With the orange sky over San Francisco, over New York, over Sydney, it’s like nature couldn’t be more gently explicit in warning us that worse is to come. She’s literally painting the skies over the major cities bright, choking orange, just for one day. But the next time, it’ll be for five days. The next time, it’ll be for 10 days.

BJÖRK: It’s mind-blowing. I remember discovering Marvin Gaye when I was 25 and listening to him nonstop for two years, but I think it had a different sort of effect on me.

ANOHNI: Because you went to music school before then, didn’t you? You were committed to the explorations you’d already been engaged in.

BJÖRK: Yeah. Kate Bush and Joni Mitchell were a big part of my influence and I owe them so much. But you’re only five years younger than me. Maybe that’s enough of a shift because the punks were listening to electronic music, like Soft Cell, but not really Motown. At least the punks I was hanging out with.

ANOHNI: Well, Soft Cell was listening to Northern soul. Northern soul was the DNA for a lot of the English new wave songs, that three-chord progression with a love song over it in a really sweet melody. That had everything to do with soul music. It was taking clinical German electronica and superimposing it on an Otis Redding song. But before Boy George, I was really into Kate Bush. No doubt, she was my first singer.

BJÖRK: Mother. [Laughs]

ANOHNI: I mean, The Kick Inside was the first record I ever bought when I was seven years old in Amsterdam. I used to perform that record and I used to do the slow motion cartwheel for all the children in the neighborhood. Because she had shot the video for “Wuthering Heights” in Amsterdam, and I was living in Holland the year that it came out. And that was the first seven-inch single I ever bought.

BJÖRK: Cool. Sorry, sometimes my questions weren’t really questions.

ANOHNI: Oh, come on. Your questions are so genius and so great.

BJÖRK: But beautiful answers. We don’t want to have it too long for these guys or they will faint.

ANOHNI: We’ll snip some of my bits out.

BJÖRK: The nip and tuck.

ANOHNI: You’re so generous to do this.

BJÖRK: It was totally my pleasure. And it’s so rewarding after you’ve had the strange job of being so self-indulgent. I spent five years writing an album on my own. It’s so refreshing to see it from the other point of view. And to do it with this masterpiece of an album, the pleasure was all mine.