Amen Dunes’ Higher Power

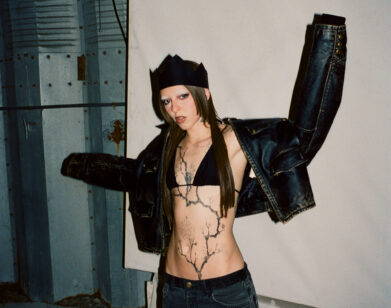

ABOVE: AMEN DUNES’ DAMON MCMAHON. PHOTO COURTESY OF TUOMAS KOPIJAAKKO

Since he started recording under the Amen Dunes moniker in 2006, Damon McMahon has been something of a lone wolf. The songs that would become debut album DIA were written and recorded alone in a Catskills cabin, intended solely for personal use. For 2011’s Through Donkey Jaw, the process was similarly insular, though there was a backing band recruited to help actualize its fuller arrangements. The music fit the setup, too. McMahon’s songs are unnerving pop affairs with traditional melodies and eerily shaky deliveries. The guitars are fuzzy, the drums subtle, and the atmosphere is exquisitely claustrophobic; it’s music made by and for its creator.

But for Love, which sees its release tomorrow via Sacred Bones, McMahon decided to take a different route. Written alongside Amen Dunes members Jordi Wheeler and Parker Kindred, and recorded with Godspeed You! Black Emperor’s Dave Bryant and Efrim Menuck, Love is easily Amen Dunes’ most approachable, outward-looking record to date. But it’s also McMahon’s most candid. The product of nearly two years of work, Love is, at its core, an album about time, memory, and connection. Its songs pose big-picture questions, delivered in a voice that’s strikingly, definitively intimate. Guided by ’60s and ’70s free-form jazz, as well as American songwriting icons like Sam Cooke and Elvis Presley, McMahon intended Love to resonate. Below, we chat with McMahon about the making of and the story behind Love.

ALY COMINGORE: When did you first start writing songs?

DAMON MCMAHON: I was 16 when I wrote my first song. I only took a year of guitar lessons when I was a kid, so it was a two-chord kind of Bob Dylan rip-off.

COMINGORE: What was your singing voice like at that age?

MCMAHON: Oh, I had no control over it. I was a total imitator. I started off covering songs. I’d get drunk with my teenage friends and tell them to pass me the guitar because I knew how to play “Helpless” by Neil Young, or something like that. I was into The Band, so I’d try to play their songs and literally just copy the vocal stylings. I didn’t know what my own voice was, so I would just imitate what I liked, I think.

COMINGORE: Do you remember when that changed?

MCMAHON: Yeah. I did a solo record when I was 25 or 26 and everyone in the media trashed the shit out of it, said I sucked terribly. I was like, “I never want to be in New York City again.” But before I left I decided to go upstate and record something that I wanted to do, something that was totally me. That was the first Amen Dunes record. In that process I think I kind of exploded out of my old self and learned to sing. It was really improvisational and free-form and weird, and it’s just kind of grown from there.

COMINGORE: Were you pretty surprised by what came out of that experience?

MCMAHON: Yeah. I had no idea what was going to happen when I went up there. I had no idea what I was saying, listening back— it just kind of came out of me.

COMINGORE: In terms of timeline, when did these songs start to take shape?

MCMAHON: Some of them are older than others. I wanted to make a really pure representation of self with this record, and there were these songs that I had written years ago that I hadn’t used because they were too honest, or something. The record is about a lot of things, but it’s partially and superficially about a relationship that ended right when I started recording it. A lot of these songs were written over the two years of that relationship.

COMINGORE: When it came time to record, were there specific goals you had in mind?

MCMAHON: Definitely. I mean, I wanted to make a record that sounded good. [laughs] To be honest, I wanted to make a record that was as beautiful as possible to be as useful to as many people in the world as possible. That’s kind of been my objective in the last couple years of Amen Dunes, and I wanted this record to be that. I had these musical inspirations that guided the process. I wanted to make my Astral Weeks—a record that was unencumbered and honest about love and these broader themes. I wanted to make a record that wasn’t hung up on self. Musically, I had these records that I really admired that were really ornate; even if they were minimal they were beautifully decorated. Whether it’s [Van Morrison’s] Astral Weeks or Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On, or a lot of late-’60s early-’70s jazz, like Pharaoh Sanders’ Karma. I started wondering what it would be like if I put these American songs to that kind of instrumentation. I wanted to put Sam Cooke, Elvis Presley, Van Morrison, all these singers in a spiritual jazz context with gothic overtones. That was the goal. [laughs] I hope it comes across.

COMINGORE: You mentioned making an album that’s useful to people, but Amen Dunes started as this very insular, very personal thing. What shifted?

MCMAHON: I think I’m a lot less sick. [laughs] But I was in this really crazy fucked place when I made DIA and the following record. But with DIA especially, it was like a death trip. It was a cry-for-help kind of record. After this relationship ended, I feel like I reentered the world. I realized that my purpose as a musician is to be useful, and I started to accept the idea that some people like my band. I could never really believe that before. I was not thinking about anybody else when I made those first two Amen Dunes records, and you can hear that, I think. And that’s not to say I think those records are bad. I think some beautiful things happen from evil music. That just wasn’t my intention this time.

COMINGORE: How did Dave and Ephrim get involved?

MCMAHON: Well, they asked us to go on tour with Godspeed You! Black Emperor in 2012 and we got along really well. I told them I was working on a new record and they went, “Oh, shit. We have a studio in Montreal. You should come up there.” So we did.

COMINGORE: How was the experience?

MCMAHON: Well, there were two sessions—one at Dave’s studio and one at Ephrim’s—and to be honest, the one at Dave’s studio didn’t really work out. It was an aborted mission. We were supposed to do the whole record there and we only lasted six days, for whatever reason. It’s like, sometimes there’s an impasse; music is some unspoken energy, and sometimes those unspoken energies get choked up. We just couldn’t get flow to happen. We did record some basics there that turned out really beautiful, though, and I think they’re beautiful as a result of the tension. You can hear the momentary relief in those recordings because we were finally able to break through and make something happen.

COMINGORE: Looking back, what do you think created the block?

MCMAHON: You know, the one thing about Amen Dunes that’s kind of weird is that the music is incredibly serious, but I don’t think we are. I think the music is so fucking serious that we can’t be serious when we’re not playing or we would just die. [laughs] I think we went up there and maybe we were not what was expected of us and I think it became confusing.

COMINGORE: Do you find that happens often, that people assume you’re this really morose guy?

MCMAHON: Yeah, I think so. I started to notice that after we play live no one talks to me. [laughs] I think it’s because we’re very intense on stage, and people think that we’re like that in real life. It’s a bummer. I do this in music so I don’t have to live this in life. That’s why I make music. I make this fucking serious shit because I want to channel that out of my life, or because it’s a way of processing it.

COMINGORE: When did you decide to call the album Love?

MCMAHON: I can tell you the exact moment, actually. I’d never listened to the band Low before, and my bandmate Parker was going to see them and just kept telling me I had to go. Someone else whose musical taste I really trust as well had said the same thing, so I went to see Low, which, for the record, is totally not my thing. But I went and I witnessed these total masters. They were so in control and so free. He’s got this incredible voice and guitar sound, and she’s just a beautiful presence and a beautiful drummer. I was watching them and the word “love” came to mind and that was it. I knew that was what I was going to call the next record. It seemed perfect for a million reasons. But I’m curious to know what other people think my intention for calling it “love” is.

COMINGORE: I think it speaks to a batch of songs written over the beginning, middle, and end of a relationship.

MCMAHON: Yeah. And that is true. There’s the funhouse mirror story for the title—that it was written over the course of this two-year relationship and it was recorded and produced during the breakup. I think people can hear it and identify with it as a breakup record. But what do you learn when you go through a breakup?

COMINGORE: You learn about yourself.

MCMAHON: Yeah. You never had that person to begin with. All you ever have is you, and you better get right with that because at the end of the day that’s all you’re ever going to have. Love is not about crushing out on a really hot girl with brown hair. That’s not love. Love is something far more severe and beautiful and stern. The love that I’m talking about is devotion. That’s why Pharaoh Sanders and Elvis Presley and Marvin Gaye come to mind. They weren’t writing about some relationship that went bad—they’re writing about fucking God, man. They’re writing about the life sentence and the lifelong gift of being a musician. You’re connecting to the universe and to other people and to yourself. That’s what this record’s really about. It’s the idea that love is really a loss of self.

LOVE IS OUT TOMORROW, MAY 13, ON SACRED BONES. FOR MORE ON AMEN DUNES, PLEASE VISIT THEIR FACEBOOK PAGE.