OPEN BOOK

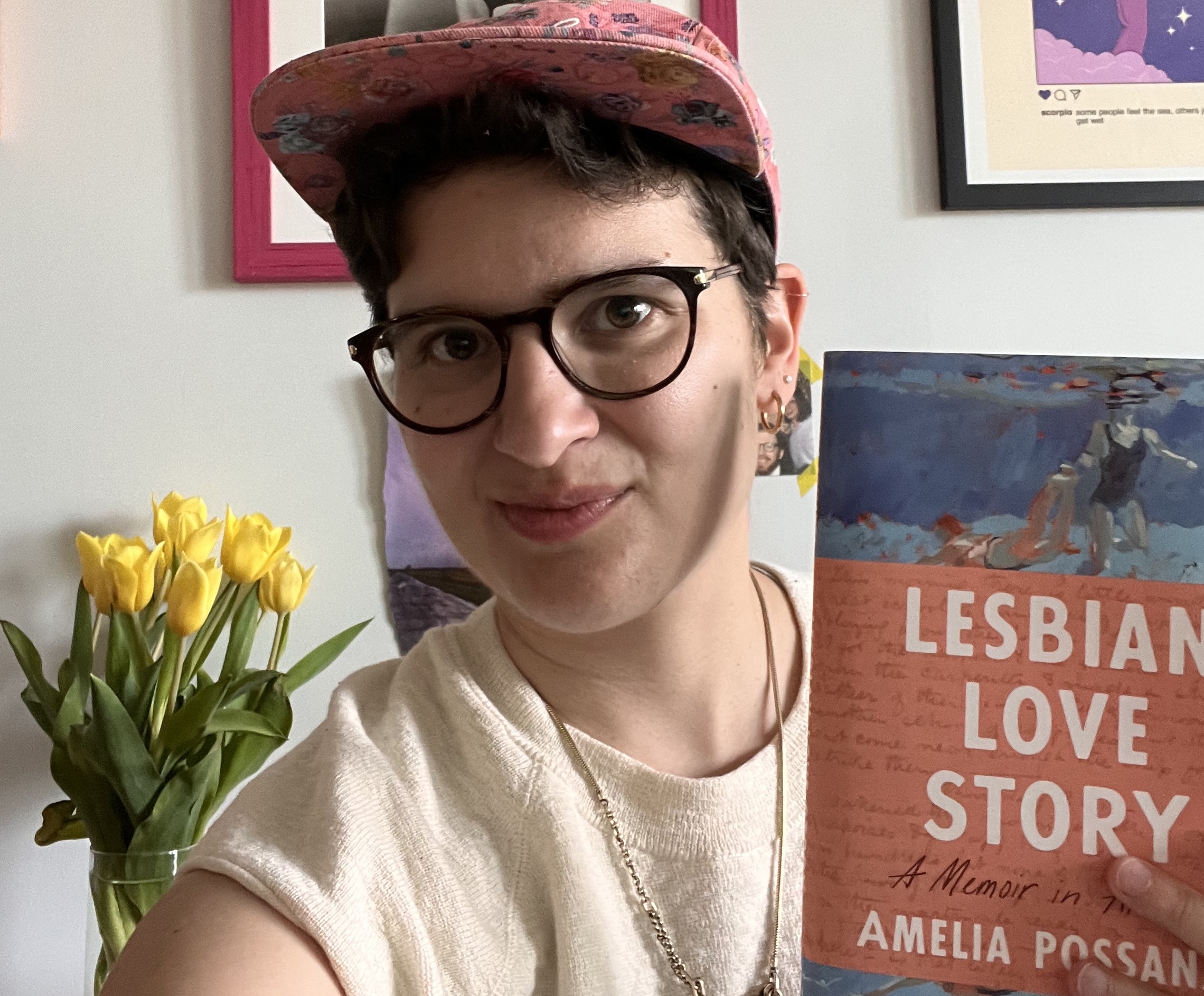

Amelia Possanza Brings History’s Lesbian Love Stories to Life

This is OPEN BOOK, a monthly column in which we ask debut authors about their reading and writing habits. Last month, we spoke with Nigerian-British author Stephen Buoro about his bold coming-of-age novel The Five Sorrowful Mysteries of Andy Africa. For this installment, we talked to Amelia Possanza about Lesbian Love Story: A Memoir in Archives, a precisely woven account of seven lesbian romances across the ages, forging a path from Sappho’s fragments to a drag king show in Bushwick. From what was once lost and obscured, Possanza offers a fresh, genre-bending lesbian canon in her effort to, as she told us, “reclaim and reinvent the intimate elements of lesbian history that have been lost, destroyed, and forgotten by the traditional archive.” Below, the author answers our questionnaire, sharing her thoughts on Moby-Dick (“just some guy goofing off”), the Sadiya Hartman book that was integral to the conception of her own, and writing on the subway.

———

Where do you like to write?

If things go according to plan, I write in the living room at an old sewing table with iron legs and holes in the top from where the D&D Machine was ripped out of the wood. A good friend of mine is a fiber artist, and she always says that a computer is just the latest, most complex model of a weaving loom. I like to tell myself that writing is a kind of sewing, even though I don’t have the technical skills to back it up. Stitching together pieces, tending to the individual seams while still keeping an eye on the overall shape. That said, most days I often procrastinate for so long that I have to rush out the front door before I get any writing done, so I have to make do with typing out iPhone notes to myself on the subway. Something about the time crunch, the forward momentum of the train, and the hum of other people’s lives sharpens my focus.

When do you like to write?

Growing up, I’d always have to wake up before the sun to head to swim practice, which turned me into a morning person at an early age. There’s no one to talk to, nothing to do. The day could be anything, blank as the page, both equally full of possibility. Sometimes, I wish it could be morning forever.

What’s the first thing you did after you turned in a draft of your book?

I immediately logged onto my work email! I work full-time as a book publicist (and, as I mentioned, I’m a procrastinator), so the day my draft was due, I got up at 6am to give everything one last look before I hit send around 9:07am, and then I switched over to my work account. Later that day, though, I ate dinner with a friend on a park bench, and my then-partner brought over a bottle of wine and a vegan cookie. I often find more pleasure in life’s little routines, like writing, than in big celebrations.

Tell us about three to five books you read while writing your own, and why?

My entire book grew out of a love of reading, and a desire to read more of what has been promiscuously said, thought, fancied, and sung of lesbians (I’m stealing Herman Melville’s words here, though he was writing about Leviathan in Moby-Dick), so it’s hard to narrow the list down to just a few sources. I know I have to include Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals because it introduced me to her concept of “critical fabulation,” a means of filling in the gaps in the histories of marginalized peoples by imagining what could have happened in a way that was still true to the time period, which became a central strategy in my own efforts to reclaim and reinvent the intimate elements of lesbian history that have been lost, destroyed, and forgotten by the traditional archive.

I had actually picked up the book to better understand the life of Mabel Hampton, a Harlem Renaissance dancer and co-founder of the Lesbian Herstory Archives who lived with her partner Lillian Foster for over 40 years. I also read one of Mabel’s favorite novels, Loving Her by Ann Allen Shockley, a 1970s novel of interracial love that was likely one of the 300 novels she donated to the Herstory Archives. It “is not a stylistically successful novel,” as scholar Alycee J. Lane writes in the forward, but I wonder how much of her own life Mabel saw reflected in both the novel’s explicit sex scenes and in the specter of physical abuse that loomed over the characters’ lives.

I discovered Chloe Caldwell’s The Red Zone: A Love Story toward the end of my writing process, and while it has very little overlap with the subject matter of my own book, it served as an exquisite model for how to combine meticulous research—in Chloe’s case, about periods and menstrual products through the decades—with vulnerable personal history.

Tell us about a formative early reading experience.

Maria Howe’s poem “Practicing” begins: “I want to write a love poem for the girls I kissed in seventh grade.” I remember catching that line out of the corner of my eye when I was supposed to be reading something on the facing page in our assigned high school literature anthology. I remember thinking, “adults are allowed to write about girls kissing each other?!”

The last book you loved, and why?

Gina Chung’s Sea Change. I came for the giant octopus named Dolores, and I stayed for the all-too-relatable plot about the difficulties of building a fulfilling life in the face of grief, family expectation, and rapid climate change.

The last book that disappointed you, and why?

Bicycling for Ladies by Maria “Violet” Ward, with explanatory illustrations based on photographs by Alice Austen of the gymnast Daisy Elliot, three little-known Victorian-era lesbians who lived and loved on Staten Island, is filled with mind-numbing suggestions for how best to mount a bicycle in a heavy skirt and maintenance instructions for a machine that has been modernized and improved upon countless times since the book was originally published in 1896. Its pages hold nothing of the romantic drama that took place behind the scenes of the book’s publication. Daisy and Violet were a romantic couple, though as the project wore on, the model’s affections began to turn from the writer to the photographer. In July 1895, likely already hard at work on the book project, Daisy wrote to Alice: “As I told Violet the other day; I love you, and should anything happen to her, you should be the first one I should turn to.” When it comes to narrative, their letters probably would have made for more interesting reading than a bicycle manual, though many have been lost, and those that remain have yet to be published widely.

Hardcover or paperback? Why?

Paperback, because I’m a monster who loves to curl back the cover (and is about to be disowned by her father for admitting this).

A book you think should be in the canon, but isn’t:

People in Trouble by Sarah Schulman is currently out of print in the US, but I’d love to see this fictionalized account of the AIDS crisis (and illicit sapphic love story) that centers queer women take its rightful place on the shelves.

A book you think shouldn’t be in the canon, but is:

Moby-Dick by Herman Melville. This is just some guy goofing off, exploring his interest in whales, having a grand old time. It’s a really funny book, and I think people miss that because it’s considered “canon.”

What’s your favorite bookstore(s)?

My mother would disown me if I didn’t name the bookstore where she works in Pittsburgh, City of Asylum, which grew out of a nonprofit that hosts writers in exile from their home countries. It’s been a pleasant surprise to watch bookstores flourish in my hometown. There are so many more now than when I was growing up! White Whale. Riverstone Books. Amazing Books and Records. Caliban Books on Craig Street, which has been around since when I used to visit my dad at work, and he would help me imagine my own book among the stacks. “Look at how many scholarly books about literature there are,” he would say. “It’s better to write your own book, instead of just writing about someone else’s.”

What do you look for in a reading experience?

I want to feel like the author is having fun, and I’m just along for the ride.

How do you arrange your bookshelf?

If I love a book, I’ll immediately give it away to a friend so I have someone to talk to about it. The downside of that habit is that my shelves are full of books that I either haven’t read or didn’t like, so I don’t put much thought into how I arrange the remaining cast-offs. When I’m about to start a new project, though, I gather up all the relevant source material and stack it up at the edge of my sewing table as an invitation to get back to work.

Have you ever lied about having read a book? If so, which one?

In first grade, I lied about reading every book that crossed my desk. I’d take one out of our classroom library, hold it open to each page for what felt like an appropriate amount of time, return it, and then repeat. I refused to accept a shiny “Book It” sticker toward earning a free Pizza Hut pizza because that felt like a step too far in my ruse. No one had realized that I needed glasses and could hardly see the text. I like to think I’m still making up for all the books I didn’t read during that lost year.