Zac Efron

Unless you’ve got children of a certain age, you probably haven’t seen much of Zac Efron’s work. This is it, so far, in a nutshell: Efron is the star of Disney’s High School Musical franchise, which ostensibly revolves around the blooming relationship between Troy (Efron) and Gabriella (Vanessa Hudgens), a jock and a brain respectively, who couldn’t be more different from each other but who discover a common ground in their mutual love for music. Their (chaste) courtship involves various plot twists and adolescent entanglements enacted through a series of song-and-dance numbers. That, essentially, is a High School Musical movie. In the past three years, Disney has produced a trio of them, and it’s now estimated that the films, plus all of the attendant HSM (as the kids like to call it) merchandising, has generated more than $1 billion in revenues. It hasn’t hurt the cause that Efron got together with Hudgens in real life, and that he also appeared in Adam Shankman’s 2007 remake of Hairspray, which raked in more than $200 million worldwide.

If you’re over the age of 12 and still have all your faculties intact, or if you’re simply a hardened preteen, then the HSM films may present themselves as the worst kind of teenage wish-fulfillment fantasy. They’re simple, sort of saccharine, and seem to exist in a kind of vacuum-packed, irony-free, alterna-reality that makes Saved by the Bell look almost dystopic. But throughout all the songs and dances and platonic romances, two things have become abundantly clear: 1) that the kids don’t care and love the movies anyhow; and 2) that Zac Efron is a star.

Efron radiates a sort of well-scrubbed young mannishness. He’s an entertainer in the most traditional sense of the word: He knows how to carry a tune and turn a step, he winks at the girls and nods at the guys, and he generally appears to be working hard not to disappoint—all of which would seem too good to be true if he didn’t seem to mean it so much. It’s no wonder that his bronzed image—those Hollywood-soulful eyes peering out from under a thick drape of artfully tousled hair—is tacked up in so many lockers, wallpapered on so many iPhones, and emblazoned on so many notebooks and backpacks.

Of course, it’s an interesting time for teen stars. There are more of them now than there have ever been, all vying as desperately for money and attention as they are to ward off the ravages of oily skin. In this air-tight job market, there’s even work for former teen stars (VH1’s Confessions of a Teen Idol) and long-forgotten ones who are addicted to drugs (VH1’s Celebrity Rehab with Dr. Drew), and there are entire networks with programming schedules built around the conceit that watching people who’ve previously experienced even the faintest whiff of adolescent fame attempting to reclaim their former glory can make for good TV (VH1). But in 2009, the blind glitz of teen idolhood can no longer hide what everyone knows: There comes a time when every teen star needs to do something radical in order to ensure his or her survival, to find some way of making a fast break out of the corner of the moment, to take a perimeter shot at immortality.

Now, Efron is preparing to take his own shot. He’s appearing in his first two post-HSM films, one of which partly takes place in a high school (and in which he, interestingly enough, plays basketball), but neither of which are musical. In director Burr Steers’s 17 Again, Efron stars as a dejected 37-year-old man (played in his older incarnation by Matthew Perry) who is in the throes of a divorce from his high school sweetheart (Leslie Mann), and who, through some mystical transformation not involving the rejuvenating talents of Dr. Fredric Brandt (see page 60), becomes, as the title would imply, 17 again. Efron also stars in Richard Linklater’s Me and Orson Welles, a period piece set in 1937 about a teenager who is cast in a fraught production of Julius Caesar put on by Welles and John Houseman’s famed Mercury Theatre company.

As hard as it might be to believe, Efron wasn’t born into performing. In fact, he only started doing musical theater and going out on auditions when he was in middle school in his hometown of Arroyo Grande, California. He landed the lead in High School Musical during one of those auditions, the summer before his senior year. We asked director Gus Van Sant to interview the 21-year-old actor. He graciously obliged.GUS VAN SANT: Sorry we couldn’t do this in person.

ZAC EFRON: It’s all good. Where are you right now?

VAN SANT: I’m in Gearhart, Oregon. It’s on the coast outside of Portland. I’m in a beach house.

EFRON: I’ve been to the coast outside of Portland—a couple of times, actually. I might have been where you’re at. I have relatives up there. I think I took a road trip from Portland one time with my aunt, because she lives there. It’s a beautiful place.

VAN SANT: It’s really beautiful here today.

EFRON: It’s pouring in L.A. [laughs]

VAN SANT: So when was the last time that you were in Oregon?

EFRON: Oh, man. It seems like it’s been years. We used to go up there all the time, but I’m stuck in L.A. a lot now.

VAN SANT: Is your schedule today really tight?

EFRON: Not today. I’m not really doing anything. I’m looking at some furniture, because I just got a new place, so I’m figuring out if I want this desk. I’m sitting at it right now. It’s a vintage Herman Miller desk from, like, 1940-something. I don’t know . . . I’m just deciding if I’m going to want it in my house, or if I’m just going to completely wreck it. [laughs] Herman Miller’s stuff is really, really modern, but they have some pretty brilliant designs. [Ed note: Herman Miller is credited with inventing the office cubicle.] I’m sitting at this desk, and it’s the most well-built thing I’ve ever sat at . . . It’s a beautiful piece. It’s got this amazing wood grain that I’ve never seen in any piece of furniture. It’s also a little pricey . . .

VAN SANT: Yeah, those kinds of things are superexpensive, right?

EFRON: Superexpensive. I’m lucky they’re letting me test it out at my place for a couple of days before I have to buy it.

VAN SANT: Oh, the desk is at your house?

EFRON: Yeah. It’s at my house. I’m sitting at it right now. I just bought this place. It’s not big or anything, but it’s a pretty unique space. It’s very modern, very clean, very simple. It’s got concrete floors so I can’t screw it up. I can skateboard inside the house . . . You know, all the essentials are there. I just don’t want to buy nice furniture and then fuck it all up.

VAN SANT: Well, you could put a protective writing pad on the desk. [both laugh] So do you actually skateboard in your house?

EFRON: I have, but now there’s too much stuff around, so it’s getting harder.

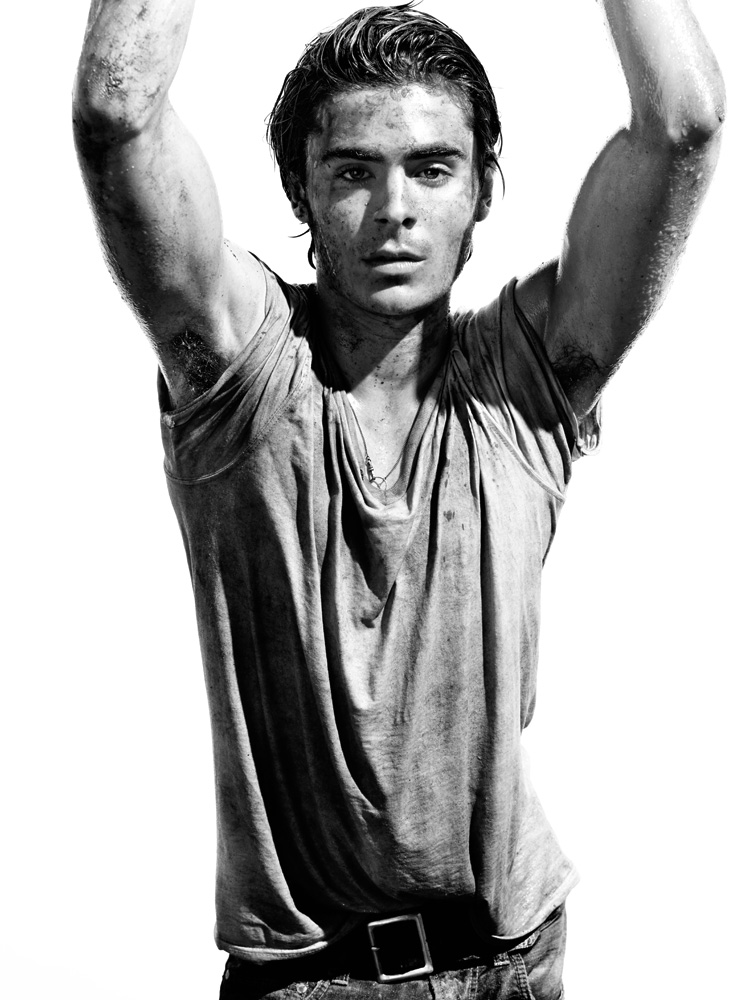

VAN SANT: Did you take any pictures for this article already?

EFRON: Yeah, we did.

VAN SANT: How did that go?

EFRON: I think it went pretty cool. There was, like, a giant sandbox in the middle of a studio, and then I just got to roll around in the dirt for a couple of hours. I got pretty dirty by the end of it, so that was fun. It was definitely different from anything I had ever done before. The photographer was really fun to work with . . . He recommended some furniture.

VAN SANT: I wanted to ask you about this Richard Linklater film. Is it Orson and Me?

EFRON: Me and Orson Welles.

VAN SANT: Where did you shoot that?

EFRON: Rick was brilliant, because he found this great theater on the Isle of Man, which, after a little bit of work, looked a whole lot like the Mercury Theatre did in 1937. We took a beautiful theater and made it look rusty and old and dusty, and, once we filled it with extras dressed in 1930s attire, the place was very believable. It even smelled like an old theater. It was pretty neat because we were basically stuck there—you know, we couldn’t leave. There was nowhere to go on the Isle of Man. So we lived in that theater for several weeks. It was fun and exciting, but it was also kind of maddening. I went a little bit insane.

VAN SANT: The Isle of Man—they have a small community there.

EFRON: Yeah, so as soon as they figured out that we were filming there, everyone in the town knew. There was always a small group of onlookers out in front of the theater while we were filming. It was pretty funny.

VAN SANT: And so the play that they’re putting on in the film is Julius Caesar?

EFRON: Yeah. Orson Welles was doing Julius Caesar, but he had a unique adaptation. I don’t know if you’re familiar with it, but Stalin was Julius Caesar in the Orson Welles adaptation, so it put a whole new practical spin on the play at the time, which was really neat.

VAN SANT: Were there any Mercury Theatre players who were still alive that you met?

EFRON: I haven’t met any of them, but I know there aren’t many who are still alive. Norman Lloyd is still around. There’s a great documentary about Orson Welles, and it has to do with William Randolph Hearst and the making of Citizen Kane [1941] . . . Welles was just hungry. He was actually doing radio to fund his theater, because, as you know, they were in the hole for most of their shows. So they were going from paycheck to paycheck just to run the Mercury Theatre.

VAN SANT: And then eventually Welles went off and did Citizen Kane.

EFRON: Yeah. I don’t think that was too long after.

VAN SANT: How old is Orson Welles in your movie?

EFRON: He’s in his mid-twenties, but he’s got the wisdom and the presence of a 50-year-old . . . Well, you know, a 30-year-old guy. [laughs]

VAN SANT: A friend of mine was Welles’s chauffer.

EFRON: Oh, really?

VAN SANT: Yeah. Welles was in his sixties, and he was in L.A. This was in the ’70s. My friend would drive him in some giant 1950s car that was painted turquoise. It was a convertible. The top was always down, and Welles would wear a huge 10-gallon hat and ride in the passenger seat, because I think he liked that people would see him and recognize him. There’s still a movie of his that we haven’t seen. I think it’s called The Other Side of the Wind. I hear it has a bunch of people playing Welles. John Huston plays him at an older age. Peter Bogdanovich plays him at a younger age. It’s his last unfinished film. I don’t know where it is, but I haven’t met anyone who has seen it.

EFRON: That’ll be interesting. People always have such a different way of playing him. They tend to go for the Citizen Kane interpretation.

VAN SANT: When is Me and Orson Welles going to come out?

EFRON: I think some time later this year.VAN SANT: But before that you have 17 Again.

EFRON: Yeah, I’m getting ready for that.

VAN SANT: Your character in the film is 37 years old, and you’re playing him as a 17-year-old. What was it like playing somebody so much older?

EFRON: At the time, it was the most unique opportunity that presented itself. There were several roles that I could have done where I would have played essentially another high school student, or they were romances or stories in a high school setting, and there were lots of things that people wanted to turn into musicals. But the whole idea of playing a 37-year-old guy as a 17-year-old was just the most exciting prospect for me. I was really intrigued by the idea. I’ve always been kind of an old man, so to speak.

VAN SANT: Was there something that you needed to do, some technique, in order to actually pull that off?

EFRON: Well, I couldn’t really relate to the character in a lot of ways, so I didn’t have that to work from. I worked a lot with Burr [Steers], the director, and Matthew [Perry], and just tried to think in terms of an older guy. He’s experienced life. He’s been through a lot that I haven’t been through yet. So it was a big change from High School Musical. You know, I’ve fallen in love, and I’ve not known what I want to do with my own future—I still don’t know. But I’ve never had a daughter who I’m looking out for. I’ve never been proud of my son. I’ve never gotten a divorce. It was interesting trying to figure that out. It was definitely a change of pace. And it was great working with Burr, because he’s got this huge imagination, and this sense of people—not what they seem to be, or what they’re defined to be, or what they want to appear to be, but as they actually are.

VAN SANT: And how old is Burr Steers?

EFRON: Oh, I’m not sure exactly.

VAN SANT: He’s not 37 years old, is he?

EFRON: Something like that. [Ed note: Steers is 43.]

VAN SANT: Oh, really?

EFRON: He knows a little bit more about what the character was going through.

VAN SANT: I wanted to ask you about video games.

EFRON: Oh, sure.

VAN SANT: Because there’s one that I used to play called Tomb Raider. Did you ever play that?

EFRON: Oh, yeah. Definitely.

VAN SANT: Is it something that people still play?

EFRON: Tomb Raider? Tomb Raider is more movie-franchise material now. Games today are a lot more fast-paced. I think at the time of Tomb Raider I was playing, like, The Legend of Zelda or something like that. That was a couple of generations ago. Now the games are a lot more about first-person shooters and strategy. They will completely blow your mind.

VAN SANT: The reason I know about Tomb Raider is from when I was researching Elephant. It was 1999, and I was trying to research the Columbine-massacre kids, and they had played video games, and I, at the time, had never really seen one. It was a world I didn’t know. And so a friend of mine just said, “We’ll just go on your computer and we can actually download a level of a game.” And the thing we downloaded was Tomb Raider. It was, like, an introductory level so you could see what the game was like. I played that for a couple of days, and I finally got the full game. But another game that I’ve played, that I think you’ve played, is Medal of Honor. That’s a hard game.

EFRON: Oh, it’s definitely a hard game. You should try Call of Duty if you ever get a chance.

VAN SANT: Is that by the same people?

EFRON: It’s just an updated, more well-rounded . . . It’s just the latest and greatest.

VAN SANT: In Medal of Honor, I developed a technique where I would try to pick off the opposition by calling up this scope and shooting from really far away. If I were going into a building or something, then I would just pick off as many people as I could before I entered.

EFRON: I always prefer that approach, too. I’m methodical—one shot, one kill. You know?

VAN SANT: Yeah. You save bullets.

EFRON: Exactly.VAN SANT: So you haven’t been to Oregon in a while, but have you traveled all over the world in the last four years?

EFRON: Yup. I’ve seen places I never dreamed of. I’ve just been exposed to a lot. The most interesting trip I took recently was probably going to Japan.

VAN SANT: Really?

EFRON: Oh, yeah. It’s just amazing. I’ve only been in and around Tokyo.

VAN SANT: Kyoto is good.

EFRON: Everyone keeps saying that: “Go to the hot springs.”

VAN SANT: One of the reasons Kyoto is really fascinating is that they have many Zen Buddhist temples. A lot of them have been turned into museums, but there are some that are still operating. The Japanese emperors, when they were battling, would get really nervous, naturally, and so Zen Buddhism was a way for them to focus and get un-nervous for their next encounter. Have you ever been to Russia?

EFRON: No, I haven’t been to Russia yet.

VAN SANT: That’s a pretty intense place. But then South America—have you been down there?

EFRON: Actually, I went to Brazil recently, but that was more of just a quick trip.

VAN SANT: Did you go to Rio?

EFRON: Yeah, I checked out Rio for a day. What a place . . . I wish I could have spent more time there.

VAN SANT: Did you walk on the beach?

EFRON: I tried. As much as I wanted to, I don’t think that was in the cards for us this time.

VAN SANT: Oh, really? Is it too crazy for you to do something like that?

EFRON: There are just a lot of people in one area, so it was too congested to walk around. VAN SANT: So that brings up the question of the paparazzi. Do they hound you and drive you crazy?

EFRON: Yeah. It’s hard to talk about it. The more attention you give to the paparazzi, the more it just, like, validates everything . . .