Winona Ryder

There was a time when Winona Ryder changed everything. She was like the new prom queen—the one who millions of brainy, brunette girls who’d long since disavowed their interest in prom queens had secretly been waiting for. (Some guys, too.) It was Heathers (1988), a groundbreaking, unsentimental (and very smart and funny) film about a pair of high school outcasts (Ryder and Christian Slater) who wind up taking out a handful of the most popular kids at school, that first earned Ryder favored-actress status amongst those of the Generation Formerly Known as X. That early Ryder image—the dark hair, the porcelain skin, the doe-like, knowing eyes, forever threatening to roll upward—very quickly became burned into peoples’ brains. It’s a singular, powerful image, and one that many directors have deployed in its variations to great effect, from Tim Burton (Beetlejuice, 1988, and Edward Scissorhands, 1990) to Francis Ford Coppola (Bram Stoker’s Dracula, 1992) to Martin Scorsese (The Age of Innocence, 1993) to Ben Stiller (Reality Bites, 1994) to James Mangold (Girl, Interrupted, 1999).The headlines offscreen for Ryder are by now well-known. Her real last name is Horowitz, and she grew up on a commune north of San Francisco. Her parents are intellectuals and writers who ran with a counterculture coterie that at various points included Allen Ginsberg and Ryder’s godfather, Timothy Leary. (If it’s any indication of their political leanings, after George W. Bush was reelected in 2004, the Horowitzes moved to Canada.) There’s her relationship with Johnny Depp in the very early ’90s, and her shoplifting arrest in the very early ’00s. But ever since the latter incident—which was followed by a five-year semisabbatical—Ryder, now 38, has led a lower profile in the tabloids, investing herself in other interests, such as writing, and acting mostly in smaller, more independent films. We spoke late one Friday night in September.

STEPHEN MOOALLEM: I was going back and reading through some of your old interviews, and one of the things that I found interesting is that you seemed so self-possessed at such a young age—and very sure of who you were, in a sense. Where do you think that came from?

WINONA RYDER: Well, I think I really scored with my parents. All of my friends pretty much came from broken homes, and my parents are still together, but not only that, they’re still in love and still write together. I really lucked out in terms of how they encouraged me to develop my own personality so I didn’t just feel incredibly insecure and like I didn’t fit in. I just felt, like, well, you know, it’s good to be different. So I never really modeled myself on anyone. I was inspired by lots of people, certainly in acting and in writing and stuff, but I never wanted to be somebody else. My parents really instilled this idea in me of being your own person—almost to the extent that I couldn’t do wrong. I’d get a bad grade and they’d be like, “No! What you did was great!” [laughs]

MOOALLEM: I always wonder about people who experience so much success when they’re so young, like you did. How do you think it affected the way you looked at acting or even just work in general?

RYDER: Well, the fact that I got into this at all was kind of fluke-ish. I loved movies, but I can’t remember ever really wanting to be an actress, and I certainly didn’t imagine ever being in a movie. I think I wanted to be a writer. When I was 12, we moved to -Petaluma [California], and at the first junior high school I went to I got really bullied. After three days, I was put on home study. We had just moved to this town, so I didn’t have any friends, and my parents, god bless them, scrimped and saved to send me to ACT [American Conservatory Theater in San -Francisco] three times a week as a kind of outlet. So I was like taking these acting classes, but I was so young that it wasn’t really in my sights to have a career.

Nowadays, it seems like these girls . . . They think it’s going to be like this forever . . . But I’ve been doing this for a quarter of a century now. I remember when so many people were the number-one person at the box office.Winona Ryder

MOOALLEM: So how did that happen?

RYDER: Well, they were casting a movie at ACT, and I auditioned, and I ended up being asked to do a screen test, so my family drove down to L.A. in our ’69 Volvo with no air conditioning. I went to the studio and there were these lights—I had no idea what was going on. I remember I screen-tested with River Phoenix. Anyhow, somehow I got the part. We didn’t have any money, and I think that might have been motivation for a lot of parents, but mine were really afraid of Hollywood. My mom was like, “Oh, look what happened to Judy Garland. They gave her pills and they bound her breasts!” You know, there are all those horror stories. But my mom also had this real passion for old movies. She started this film society in Minneapolis with her college boyfriend, so she knew how to run a projector, and when we lived on a commune she would screen these classic movies in this barn on, like, a sheet, and everyone would sit around on backrests and futons. So I loved movies, and she did too, but both of my parents were very worried. They were very protective, and one of them was always with me when I was working. I couldn’t work during the school year and I had to maintain a 4.0 GPA. I was supposed to audition for River’s Edge [1986], and there was a sex scene in it or something, so they were like, “No, you can’t. You’re too young.” [laughs] It’s funny because in the scripts for my first four movies, my character was always described as “homely” or “freakish.” I was actually really into that because I loved Ruth Gordon and I wanted to be like a cool character actress. And so I think, in L.A., when people would hear that I turned down a movie or I passed on a project or I wouldn’t come in on something, it made them kind of intrigued. But it was also weird, us being so choosy, because we couldn’t afford to drive down from Petaluma for every audition.

MOOALLEM: How did Heathers happen?

RYDER: Heathers came around when I got the script from Michael McDowell, who wrote –Beetlejuice. I read it before it went out to people and I freaked out. I called Michael Lehmann [the director], and I was like, “You don’t have to pay me. I just want to say these lines.” And at first they didn’t want me. It’s actually on the commentary for the DVD, which is kind of nuts. Dan [Waters, who wrote Heathers] and Michael are talking about casting me, and they say something like, “Remember how we didn’t think she was pretty enough?” But when I heard that, I immediately went to some mall makeup counter and had them put makeup on me, and then I went back and convinced them to cast me. So even though Heathers didn’t make a lot of money, I really was able to transition into a situation where people thought I could play an attractive role because of it.

MOOALLEM: It’s such an influential film.

RYDER: That movie probably did a lot more for me than I even knew at the time. It never made any money when it came out—it made like a couple million dollars—but I felt like everyone saw it. Some people were even offended by it. I mean, it is very ’80s, but I think it totally holds up.

MOOALLEM: You know, they’re trying to make it into a TV series.

RYDER: Someone just told me that today. Is that true? Because I also heard that they’re trying to do it as a Broadway musical.

MOOALLEM: I heard that. And then I’ve heard things over the years about a sequel.

RYDER: Well, see, I have always wanted to make a sequel, and I’m always bugging Dan and Michael about it. I mean, the only way I would ever do it is if it was the same group of people, and they’re always sort of like, “Yeah, right.” But people do come up to me on the street and ask me about it. Dan Waters came up with this idea. I guess he was sort of joking, but he had this idea of, like, Veronica Goes to Washington, where the first lady is like the ultimate Heather. So I still have like this shred of hope, but I guess it’s probably not going to happen.

MOOALLEM: Well, the movie was years ahead of its time. People didn’t write films about teenagers in that way, with that sort of sensibility, before Heathers. Things like Twilight and even Gossip Girl probably wouldn’t exist the way they are now without that movie.

RYDER: We were joking about taglines on the set, and we came up with one that was, ‘Love. Lust. Murder. Heathers: The Last Teen Film.’ We really wanted to make the teen film to end all teen films. But it’s weird because I feel like when I saw Mean Girls [2004], which was directed by Dan’s brother [Mark Waters]—which is kind of strange in and of itself—it’s a nice movie, but I remember feeling like I wanted them to say that there was some influence, and they kind of deliberately didn’t say that. I mean, it’s got to be flattering for Dan and for Michael that they want to make this TV series, but I’m not sure what to think about it. I’m curious how it’s going to work. Heathers was once on Comedy Central or something, and they had to bleep every other word—although, I guess on TV now you can get away with saying a lot more.

MOOALLEM: I think they even sort of get into some low-grade swearing on Mad Men.

RYDER: They do, right? I actually just started watching the first season of Mad Men. Does that guy have like a whole different personality or something? [sighs] I’m so confused! I also just got into The Wire. I really wanted to watch it when it was on, but I was, like, always working or something. But I just watched the box set and I love that show. It’s the greatest writing. I loved that show Homicide: Life on the Street that [The Wire’s creator] David Simon did before The Wire, and I actually read that book he wrote [Homicide:A Year on the Killing Streets]. That guy is incredible. But there’s some hardcore stuff in there.

MOOALLEM: Would you be interested in doing something like that at some point? Does the idea appeal to you at all?

RYDER: I think it would be kind of cool to do a series like that, but then every actor has that fear . . . You would want it to get picked up, but then it could be like six years of your life. But TV is such a different medium now. I would, in a heartbeat, do something like The Wire. If you just really love acting, then it doesn’t matter what format it is. You just want to do a great part.

MOOALLEM: Obviously, you did a little thing in Star Trek as Mr. Spock’s mother, but aside from that, a lot of the films that you’ve done over the last several years have been smaller and more independent. Did you make a conscious decision to move in that direction?

RYDER: Yeah. The industry has really changed a lot. I don’t really understand the business part of it—I don’t really follow it—but you certainly feel the repercussions. Some of the movies I’ve done have not turned out how I’d hoped they would, but then a lot of the studio stuff out there was just those sort of genre films, and I’ve just wanted to do more interesting things. Some of the ones I’ve done were actually good experiences where the movie just didn’t really come together in the end, but the important thing for me is that I wanted to go back to how things were when I started, where there was always this feeling that I was taking a chance.

MOOALLEM: When you were younger did you ever get into one of those situations where you were doing back-to-back-to-back films?

RYDER: I did that when I was in my late teens and then I totally had a meltdown because I was so exhausted. I mean, I wasn’t in one movie that was an overnight sensation—you know, like Pretty Woman [1990] was for Julia Roberts. So I was lucky in the sense that my success was gradual. But then there was a point when there was so much attention, and you get surrounded with people who sort of make you feel like you have to do everything or else it’s all going to go away. It’s really sweet when younger actresses come up to me. It’s so touching because I know how they feel. I know what they’re going through. It’s really tough to suddenly be very famous. I think you get this feeling like you have to kind of be what everyone thinks you are, and if you slow down, then it’s all going to go away. If anyone ever asks me for advice, that’s sort of what I tell them: that they shouldn’t feel like they have to live up to all of this, and that it’s important to try to have a life outside of it—even just for your work. It’s like, sometimes I’ll watch a movie, and it’s got some big star in it playing a working-class person, and the character is in a grocery store, and you can kind of tell, from just watching the scene, that this actor doesn’t do their own shopping. So you have to have some sense of reality. That’s why, at the height of everything, I used to go to the Laundromat to do my laundry—just because I had to sort of maintain.

MOOALLEM: What did it feel like for you at that time? You were getting a lot of attention, obviously, for being in movies, but also for your personal life.

RYDER: I think when all that was happening, I did sort of get trapped into working too much. And then I sort of had . . . It wasn’t like a breakdown, but I was just exhausted, and I had to just stop and take care of myself. And then I kind of segued into only wanting to do one movie a year, and I was so lucky that I was able to do that. Even though I never really had to pound the pavement as an actor, I always worked really hard. But, at the same time, I always felt like people thought that I didn’t have to struggle even though I was struggling. I approached work very seriously. I never went out. I couldn’t fathom people who could go out to clubs . . . I mean, if I had a 6 a.m. call, I had to be prepared. I had to be in bed at a certain hour. But I definitely went through a time where I was just terrified and exhausted and I didn’t really understand. The world just seemed, or Hollywood . . . It just got to be too much for me. My problems seemed so glamorous to other people, and everyone just thought I was so lucky. But then, I was lucky because my family was really there for me—San Francisco was a real refuge. I think I just felt like I really wanted to hold on to who I was as a person, and try to—for lack of a more interesting way to say it—have as much of a normal life as I could.

But it was hard. Nowadays, it seems like these girls . . . I know how they’re feeling. They think it’s going to be like this forever so they’re not being more -careful. But I’ve been doing this for a quarter of a century now. I remember when so many people were the number-one person at the box office. And I’ve also seen so many people crash and burn, or be on top and then just make some bad choices.

MOOALLEM: When do you think things really changed for you in terms of your relationship with the idea of being a movie star?

RYDER: I was never strategic really, but back when I was starting out no one cared. In the acting community, box office didn’t matter. I really think it was a mistake when they started paying people like $20 million to do a movie because now it’s all people think about. Is she worth it? Is he worth it? That’s got to be a rough feeling. I’ve never been paid anywhere near that, but it does sort of take away from the movie because no one else is getting paid like that. And then, as an actor who is paid that much money, you have to maintain this thing. I think, in a way—even if it was a little bit subconscious—when that started happening I really didn’t want to be a part of it. Maybe it was just out of fear, like I don’t want to hear someone say, “Is she worth it?” But also there’s this vibe of camaraderie on the set if everyone is doing it for the art of it. The great directors understand that, and aren’t just sitting there reading the trades and wondering how we can make this the most commercial film ever made. I mean, on this one I did, The Private Lives of Pippa Lee, the director, Rebecca Miller, was so amazing. On most of the other movies I’ve done, you’re just constantly aware that they don’t have the time or the money, and you just feel that pressure. But Rebecca just really kept it away from us—even though I’m sure it was there. Then there’s also this thing with actors—and we all talk about this, even like really big actors—and it is what happens when the movie ends and you’re just sitting at home. If you’re a musician, you can practice your guitar every day and write songs, but when you’re an actor, you can’t just like burst into a monologue. Your only exercise is when you’re in prep or you’re working. If you know you’re going to do a movie in a couple months, then you can start researching and developing your character and stuff. But most actors don’t know what you’re going to do next, so you get into this thing where you have to sort of force yourself to have another life outside of acting. And then, as soon as you start something in this sort of normal life that you’re trying to live, you get a job. So you have this sort of constant struggle because you want to be able to commit to things and to finish things in your life, but then you also want to be able to act.

MOOALLEM: Do you still write?

RYDER: Yeah. I write pretty much every day, but I don’t have any desire to publish anything. I mean, years ago, I wrote this short story, and it got -published in some really tiny zine. I did it under another name. But it was the greatest feeling because people talked about it and they didn’t know it was me. I can’t even describe the feeling. It was like, -people liked it, but none of my baggage got in the -way . . . But I do still write. There’s something about it that I just keep coming back to. I actually just -finished American Pastoral, which I didn’t read when it came out, but I really love Philip Roth. When I was reading it, I was just thinking about how these great fiction writers can write so beautifully and painfully about something that they didn’t experience. It’s just amazing to me.

MOOALLEM: Well, it’s interesting that you say that, though, because you kind of do that in a different way as an actress. You constantly have to find ways to access things that you haven’t necessarily experienced.

RYDER: I guess that’s true. I remember, when I did The Crucible [1996], there was literally nothing from my own life that I could call upon—-nothing even remotely close. But I have had that experience before, certainly on period pieces, which I love doing. I’ve learned so much making those movies. For six months, I’d study. I’d learn things like the etiquette, or what the medicinal things were at the time, or why, when you walk into an old Victorian house, the room to the right, with the chaise lounge, was designed for fainting, so women could go and pass out. I just loved soaking that up. But I’d done a few period pieces in a row, and then

I got the script for Reality Bites [1994], and literally it was all about the fact that I could wear jeans. Oh god, corsets . . . They’re great for your performance because then you feel so repressed, but they take their toll. I would love to get back in one, though.

MOOALLEM: The Catcher in the Rye comes up a lot in your old interviews. Are you still a big fan?

RYDER: I was and still am. It’s weird because when you first read that book, it’s so personal and you feel like you’re the only one who feels that way, and then you realize that everyone has had that experience with it. But Holden Caulfield was like my best friend when I was a teenager. Salinger is someone whose work I just love so much, and I totally respect how protective he has been about his privacy. My dad saved every New Yorker that J.D. Salinger ever had a story in. Actually, one thing happened . . . I’ve never actually told anyone this, but when I was 19, some, um, [pauses] my boyfriend at the time bought me at an auction a Christmas card that Salinger wrote someone in the ’50s. It was literally just like, “Merry Christmas!” But Salinger’s signature was on it. I kept the card for a few years but I felt so guilty, like he wouldn’t want me to have this, so one day I decided I was going to send it back to him. I wrote this letter, and I tried not to gush, but I was like, “Dear Mr. Salinger. I received this as a gift because I’m a big fan, but I want to return it to you because I respect your privacy.” And then, sometime later, I got a thank-you letter.

There was a point when there was so much attention, and you get surrounded with people who sort of make you feel like you have to do everything or else it’s all going to go away.Winona Ryder

MOOALLEM: That’s insane!

RYDER: I know! It was amazing. I mean, it’s possible that his publisher just typed it and had him sign it or something, but it was the greatest thing ever—especially since he’s someone whose work has been so important to me. There was also that woman, Joyce Maynard, who was selling those letters that he wrote to her. He had had some affair with her or something, and she sold the letters. It’s just like, ugh. You know? I mean, I still write letters, and not that anyone I know would do that or that anyone would care to read them, but it does make me pause. I don’t know how safe e-mail is either because things get leaked out on that, too. Having had a public relationship, I remember, back then, doing an interview where I was like, “I’m so in love.” And then, time goes by, and you just kind of don’t want that out there, you know? But, at the same time, I’m really lucky because my parents have this entire record of my life. They’ve got copies of every magazine I was ever in. They’ve got all of these Polaroids from wardrobe fittings, and all the stuff from Beetlejuice, everything. My parents have just collected it all. My dad even signed up so he could get Google alerts about me, but then he had to stop because he’d get these things where people would put my face on some Anna Nicole Smith–like body, and he got totally freaked out. [laughs]

MOOALLEM: It must be incredible to have all of that stuff, though.

RYDER: Yeah, it is. Although, if someone was there to see me going through all of my stuff . . . You know, you do things in the moment, and then you change, and then they’re just out there. I guess I just have a really big scrapbook. But I’m really kind of glad. I still actually have these notes that Marty Scorsese wrote me while we were making The Age of Innocence [1993]. If he couldn’t make it into the carriage where we were filming or whatever, he would send me little notes like, “Remember to kiss him at the end.” I save everything, so I definitely have that gene in me. Someone was telling me about this show called Hoarders. I was like, “Oh no! I save everything!” I’m scared I might be a hoarder.

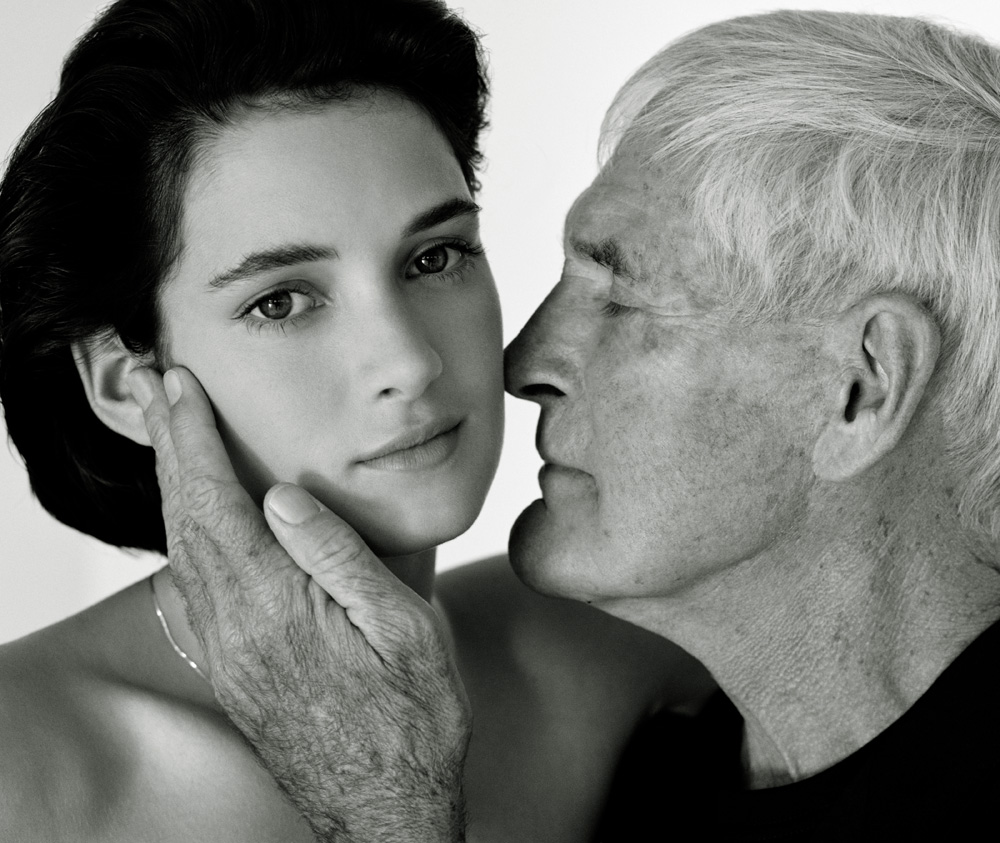

Photo credit: Winona Ryder and her godfather Timothy Leary from Interview, November 1989. Photo: © Herb Ritts Foundation.