The secret history of New York’s craziest social experiment

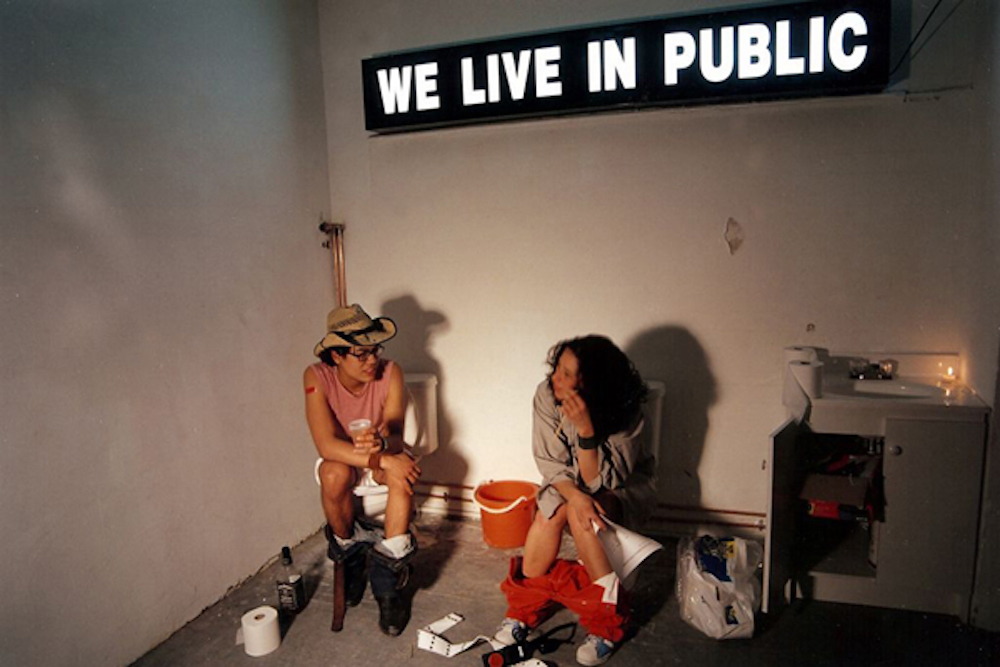

STILL FROM WE LIVE IN PUBLIC COURTESY OF INTERLOPER FILMS

In 2014 my friends and I threw a Halloween party in a strange subterranean warehouse space beneath Tribeca, which at the time was named Bathhouse. You entered through the street level through an unassuming door on Broadway and took an elevator two floors down—the cavernous space opened up hundreds of feet back. It was, at the time, being rented by another friend of ours, a reclusive hairdresser who used it for private appointments and commercial shoots. Brutalist and eerie, it felt like the perfect location for a Halloween bash.

Two weeks before the party, I happened to stumble across a documentary on one of the strangest performance art pieces that’s ever been staged in New York. The 2009 documentary, directed by Ondi Timoner, was titled We Live In Public. The story is this: in the mid ’90s, a dot-com millionaire and son of a CIA agent named Josh Harris became increasingly disgruntled with the buttoned-up business world, and quit his job. He devoted himself to a strange series of projects, which culminated in the year 2000 with the art piece and anthropological experiment Quiet: We Live in Public, in which he turned an underground bunker in Manhattan into a capsule hotel, and filled it with nearly 150 people. For a month, they did everything together—ate, slept, showered, and had sex. Harris even set up a gun range, and participants fired semi-automatic weapons deep underground. The entire space was hooked up cameras; everything was broadcast online. It was a precursor to Big Brother, the reality TV show about strangers living in a house together on camera. Alanna Heiss—at the time the director of the P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center in Queens—took part in the experiment, which she refers to in the documentary as “one of the most extraordinary activities I’ve ever attended anywhere in the world.” People managed to live in the bunker for a month—shitting, showering, and firing weapons—before police shut down the project.

Harris’s piece predicted a world that was just becoming visible on the horizon, in which everyone would exchange privacy for constant, never-ending connection with the wider world. “It’s a prophecy for everything from reality TV to social media, oversharing, and lack of privacy and intimacy, new ways of forming intimacy,” explained Timoner in an interview with VICE, adding that this was “all kind of set forth in the bunker in a way, and very hard to really decipher until Facebook.” The project is compelling both on its own merits—an exploration of how constant media exposure warps the social contract—and as a document of pre-gentrification Manhattan, when freaks could take over bunkers and summon the future, guns and all.

As I watched the documentary, I found myself overcome with déjà vu—where had I seen this particular combination of pillars and stairways before? Then it hit me: this was the same space we’d rented for our party! I checked in with the friend we were renting it from and he confirmed my suspicion; he’d even found bullet casings from Harris’s gun range in a closet. At the party itself, this secret history added a charge to the room. On Halloween, a night when borders between art and life become especially porous, I could almost see ghosts of the participants from the experiment dancing around us. Every Instagram post from the party felt like a nod to the images captured in the space 14 years earlier.

Two weeks after the party, Bathhouse was torn down and redeveloped into condos. Even as Harris’s prophecy increasingly reflects modern life, the unhinged New York in which he manifested it fades further into memory.