brotherly love

The Lucas Brothers Discuss the Philosophy Behind Their Film, Judas and the Black Messiah

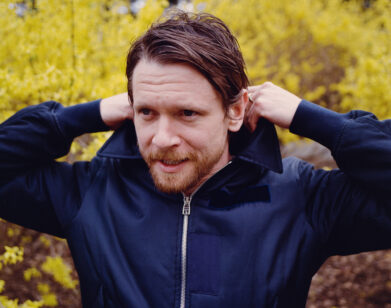

The Lucas Brothers. Photo by Brian Friedman.

Together, the twin brothers Kenny and Keith Lucas have come a long way. Born in Newark, New Jersey, the 35-year-old Lucas Brothers, as they are affectionately known, studied philosophy in college before enrolling in law school (Keith at Duke, Kenny at NYU). Before graduating, though, they both dropped out of their degree programs and took up stand-up comedy, often performing side-by-side, finishing each other’s sentences with dry wit.

Since those early days, the Lucas Brothers have earned spots at top comedy festivals, created a cartoon for FX (Lucas Bros. Moving Co.), acted in shows like Lady Dynamite, and, most recently, written the screenplay for the much-anticipated Fred Hampton biopic, Judas and the Black Messiah, starring LaKeith Stanfield and Daniel Kaluuya. We caught up with the Lucas Brothers to ask them about the film, what philosophical dilemmas they may have had to unpack while doing so, what it’s like to work with your twin.

———

KEITH: Shall we start at the beginning and talk about our roles on the film and what it was like to work with stars like Ryan Coogler, Dominique Fishback, LaKeith Stanfield and Daniel Kaluuya?

KENNY: That’s a great idea, Keith! We’d been toying with the idea of trying to get a Fred Hampton movie made. We just kept kicking around the idea. We knew we didn’t want it to be in the traditional biopic formula. So, we dug deep and we found out about William O’Neal who was an informant for the FBI, a part of the “Ghetto Informant Program” that was started by Hoover and the FBI in the ’60s to help, you know, neutralize radical movements. We were overwhelmed by his story and so we put together the initial treatment of the movie based on William O’Neal’s perspective. We pitched it around town to see if there would be any suitors and we didn’t really land anything. So, we hooked up with Shaka [King], who is the director and also co-writer of the film, and we just hammered out a more detailed story treatment for the film. We also acted as producers on the film. The whole experience was one of those things that, like, you see films one way and then you go through this process and you come through it seeing film in an entirely different perspective and I think it’s fundamentally altered my relationship to film and writing and production tremendously.

KEITH: Can you elaborate on that?

KENNY: Our relationship with film prior to this process was one of interest. We had acted in films so we understood it from that perspective to some degree, but we always had a fascination with, “What is it like to be a part of the entire process of filmmaking?” From conception of the idea to the development of the idea to pre-production to production to editing to release. Before this process, if I knew of a film that, say, got poor reviews, I’d probably shit on the film. But now I’m like, “Well, what went into the process? How much did they sacrifice before it came out?” I’m just a little bit more respectful to the process than I was prior to it.

KEITH: Me too.

KENNY: How do you think us being twins helped us to understand the story of Fred Hampton and William O’Neal?

KEITH: Even from the conception of the idea, that duality was baked in. We had an opportunity to study philosophy in college and one philosopher that really played a huge role in shaping how we approach comedy and drama and everything that we write was Hegel. He speaks a lot about the Hegelian Dilemma. And what was the…?

KENNY: The dialectic.

KEITH: Yes, the dialectic and the synthesis. You know, antithesis and the thesis and bringing those two things together to make a synthesis. I think that’s what we were trying to do with the film itself. Fred represents idealism. He represents a certain aspect of freedom and wishes for a more idealistic viewpoint. And Bill represents—

KENNY: Nihilism.

KEITH: Yeah, almost. Just a complete lack of feeling toward a cause. So, we thought if you smash those two things together, you get a better understanding of how folks were living. I think with a lot of films, sometimes they take it from the perspective of the idealistic person. You hardly ever get the viewpoint of the Bill O’Neals.

KENNY: The cynic.

KEITH: Especially with Black films. And we felt like this would be an opportunity to show that viewpoint because it was just as—I don’t want to say just as important, but it was certainly there. I would argue that the idealistic radical is way more, as far as being from an inner-city—

KENNY: It’s less common.

KEITH: Yeah, idealism is less common. You definitely get, especially where we come from, there’s a lot of cynicism. There’s a lot of nihilism. There’s a lot of apathy. Again, I don’t think that’s often portrayed in cinema, especially from the Black experience. I get it, you want to be more hopeful with the movies that you make. But if you want to depict in a realistic fashion what that viewpoint is, you have to show the other side. I think that us being twins and being philosophy majors and arguing back and forth and always having multiple viewpoints when we approach things certainly helped shape the story.

KENNY: It did.

KEITH: Kenny, how do you think growing up in Newark influenced your understanding of the story and even of the Black Panther Party itself?

KENNY: Growing up in Newark, right from birth, you’re inundated with Black radicalism at every level.

KEITH: Yeah, I mean, it’s the home of Amiri Baraka. He was the founder of the Black Arts Movement. His ethos shapes the city.

KENNY: That certainly played a huge factor. I remember when I was maybe seven, we spoke in school about King’s assassination and we were shown pictures of the funeral and you’re taught about the difficulties of being an African-American in America in Newark from an early age. Then you look around your city and you see that it’s dilapidated and you see crime and all these things. So that also reinforces your perspective of that relationship between being a Black man and being an American. Are we full citizens? Because if we are full citizens, then why are we living in such squalor? Why are our basic rights not respected like others? So, it’s either you’re not a full citizen or you’re some sort of other. You feel it instantly when you’re in Newark. There’s a lot of hope in Newark but there is also a ton of cynicism.

KEITH: Right.

KENNY: Being in Newark, that’s how our philosophy developed. You have that hopeful exuberance but always creeping underneath you is a level of apathy. Again, I think if we weren’t from Newark, we wouldn’t have been able to come up with this story. Because I don’t think we would have understood someone like Bill O’Neal. But being from Newark allowed us to both understand Fred and Bill, which then helped shape the story.

KEITH: Kenny, did your view of the world change in any way as a result of writing the film?

KENNY: That’s a great question, Keith! My thesis in college was about liberty. In particular, I studied John Stuart Mill’s conception of liberty and I analyzed it in the sense of whether or not he commits himself to a positive interpretation of liberty or is it a negative interpretation of liberty, as articulated by Isaiah Berlin. So, in the film, that’s a central conflict. Hampton’s conception of liberty is almost certainly positive. You have to enrich people to get to a point where they understand that they’re not slaves and that they can…

KEITH: I mean, he says it. Once you have free healthcare, once you have free education, you free yourself.

KENNY: Right. That’s a more positive version of liberty, whereas I would say Bill is more in the grain of the negative conception of liberty. If you have money, if you’re free of your indictments, if you’re free of criminal charges, you’ve attained a level of freedom. It’s all about money for Bill. And I think that’s indicative of America’s struggle with liberty. Is it more of a positive conception of liberty or is it a negative conception of liberty?

KEITH: Yes.

KENNY: You see that battle playing out right now. You have someone like Trump who is squarely committed to a more negative version of liberty. Trying to avoid arrest, over-valuing money. Then you have someone like AOC, who believes in free healthcare, free medicine, free education. These are the things that are going to make people whole. That’s a battle that is inextricable to the American way. I think it plays out profoundly between Bill and Fred. If you watched our cartoon, it’s certainly a little bit more nihilistic. I mean, we speak a lot about death and we talk a lot about just giving up. We couch it in terms of comedy but that was pretty much our philosophy.

KEITH: Right.

KENNY: “Happy nihilism,” as someone said. We were committed to it. But after going through this process and learning more about Fred and his commitment to the people and his willingness to sacrifice his life for the betterment of others, it changed me profoundly. And then being on set and seeing all of these people commit to this project in a way I’d never seen people commit to a project, it was very spiritual. I certainly, after going through the filmmaking process, have rejected nihilism. I just have more faith in people. People committing themselves to something bigger than themselves. And especially after Trump—that’s what nihilism gets you.

KEITH: Right.

KENNY: The end result is the Trump administration. And I don’t want my philosophy to be associated with something that led to Trump. It’s better for humans to just be more hopeful, to reach out to others, to try to help people and be committed to uplifting all.

KEITH: That’s what Fred was all about.

KENNY: I never appreciated our Democratic ideals as much as I do now after seeing the assault on Capitol Hill. I’m like, “Oh, now I get why we care so much about these ideals. Because they can be taken.” They’re not guaranteed. There’s no guarantee for them to be bestowed upon us. We have the cherish them. Yeah, nihilism is a simplistic worldview, in my opinion.

KEITH: I think it is very simplistic.

KENNY: What did you think about the movie’s ending? With the use of that documentary footage of Bill talking about Fred years later?

KEITH: Once we discovered that interview, we were doing a lot of research. We didn’t have video footage of it. We just had the transcript. You know, he outlined the story, and we were like, “Oh man, this is fascinating! He says a lot of things, but you just don’t know how he really feels about it.”

KENNY: Yes, we found an article in the Chicago Tribune from 1990, I believe, and it was Bill’s uncle speaking about the accident. He says something that I thought was pretty, not fascinating, but it stuck with me. He said Bill could no longer deal with the weight of what he did to Fred. On Martin Luther King Day, he kills himself. I mean, that could not have happened in a vacuum. There’s no way he would decide to take his own life on that day after the interview drops after he cleared his conscience and revealed that he was the informant that got Fred killed. I think he was deeply overwhelmed by it.

KEITH: So, Shaka was able to find the actual interview, the full thing. When we’re watching this interview, we’re just floored because we’re just looking at his eyes and how shifty he is and how he’s just like saying all these things, but once you find out he kills himself, you’re like, oh, this is his plea. This is his final call, essentially. We were like, “We have to put that in the movie.” People need to see the actual man. You’ve seen this picture of him but you need to see the actual man and hear his actual words. The last frame and the last thing that he says, it’s just like, this guy has lost his fucking mind. He believes he’s committed himself to a cause, but then you’re like, what cause did he commit himself to? When you find out he killed himself, it’s like, oh yeah, he was fucked up. He didn’t know what he believed in. We just thought that would be a powerful way to conclude.

KENNY: We called it Judas and the Black Messiah, and the title was a direct nod to the Judas of the Jesus story, who kills himself. We were borrowing from that.

KEITH: It felt very biblical.

KENNY: He’s a character that’s going to be hard for people to sympathize with, but knowing that he did kill himself at the end… well, maybe he felt some sort of guilt for what he did.

KEITH: Yeah.

KENNY: Do you think Bill’s hand was forced, in the end?

KEITH: I used to think about it like that, but now I always think that Fred was also young. He was also given a prison sentence and instead of betraying his crew, he was willing to take his time. So, I don’t want to take all of Bill’s agency away from him. I don’t want to make it seem like it was just a patsy or a pawn. He made some shitty choices and his hand was forced. But there comes a time when you have to make the right choice or make the wrong choice. Clearly, his decision-making led him to eventually kill himself.

KENNY: It did.

KEITH: Kenny, there’s some Oscar talk about this movie these days. What do you think about that?

KENNY: You know, I’m torn. Because on the one hand, I want the film to reach the highest level of artistic achievement possible in order to not only spread the message of Fred, but also to lend some validation to the process that we undertook in order to get the film made. So, I can see why people want the award. Also, for pragmatic reasons, you get more money and you get more prestige. But then on the other hand, well, Fred wouldn’t care. It seems so weird to tell a story about Fred Hampton and then to also care about being validated in a capitalistic way with metal.

KEITH: Right. And with that said, we have a profound respect for the Academy and we are students of the Academy. We watched the Oscars with our mom growing up. It’s just something that’s part of our identity. We’re super honored that folks are even talking about this movie. And Fred was a committed socialist. He didn’t care about awards and money and material. So, you don’t want to get caught in that trap. But on the same level, I think his story and this movie warrants that sort of recognition. And if it was to happen, we would be deeply, deeply honored.

KENNY: Absolutely. We get asked this question a lot, so let me just ask you and end it here: What is it like to work together and share in the work with me, as your twin brother?

KEITH: It’s sacred. I mean, I hate to sound so cliché or like a greeting card, but it’s the reason why we do it. When we began this process, we dropped out of law school and we didn’t know where this journey was going to take us. We had no idea that we’d be here at this very moment. But the beauty of it all is that I get to work with my brother.

KENNY: Me, too!

KEITH: That was the underlying reason why I was so committed to the journey. We could still just be doing standup, and I think I would be thankful that I get to work with my brother in so many different arenas. We get to do so much together and I think that the journey would have been a lonely one with just me. Having you with me allows for me to appreciate this process even more.

KENNY: I look back at the journey and I look at where we are now and I look at the film coming out and I see people interpreting the film, and they talk about certain reference points. They talk about The Assassination of Jesse James, I’ve seen references to Sydney Lumet. Then I think about all the times we just sat down and watched those movies years ago together. It’s so weird to be able to interpret a piece of our art while talking about things that we did just as brothers before we were even in the business. It becomes surreal and full-circle. It’s just crazy how it all works. Having someone like you to share the journey with makes it even more unreal. To be able to just talk to you about these things from childbirth until now, it’s incredible.

KEITH: It’s one of those things that hardly ever happens, and the fact that we get to share in this moment is just remarkable to me. We’re twins, we’re close, we do everything together. But to be able to reflect on our work and to collaborate with others, too, together, I think is just a beautiful thing.