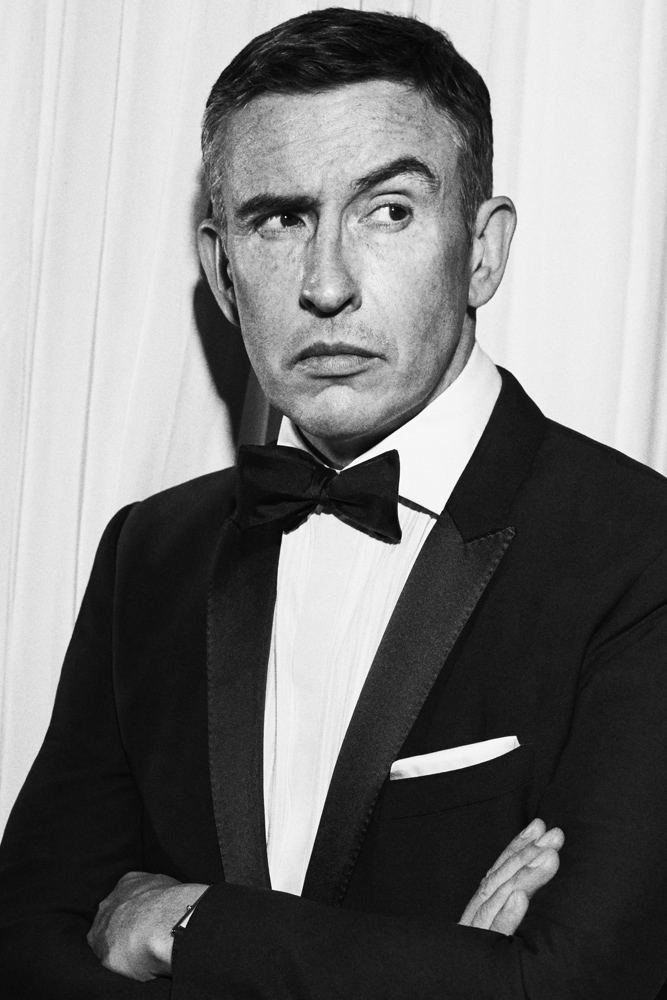

Steve Coogan

“IT’S OUR IMPERFECTIONS THAT MAKE US VULNERABLE, MAKE US INTERESTING. HOW CAN I MAKE MYSELF A BIT OF AN ASSHOLE AND STILL HAVE HUMANITY ABOUT IT?” Steve Coogan

ABOVE: STEVE COOGAN AT BLAKES HOTEL IN LONDON, JUNE 2014

Steve Coogan conceives of and performs characters that he swaddles in humor so as to smuggle delicate, poignant, and often painful truths to the viewer’s attention. And the funnier these characters are, it seems, the darker and more penetrating their payload. Case in point: Coogan’s beloved and lovably loathsome Alan Partridge—a recurring star in over 20 years of radio, TV, and film—is an entirely un-self-aware radio DJ and a total twonk. But the way Coogan has played him is endearing enough to make Partridge’s foibles feel like, if not entirely our own, then at least close enough at hand as to give us a tickle. Partridge is something of a challenge to our own vanity, ambitions, and self-estimation, even as he is simply and thoroughly outrageous entertainment.

As a pure performer in a wide range of movies, from Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette (2006) to the farcical Hamlet 2 (2008), from the big-budget fantasia Night at the Museum (2006) to the screwball political satire In the Loop (2009), Coogan has consistently delighted in playing the delusional fools whose delusions are beginning to give way. As the poncy director getting more than he bargained for in Ben Stiller’s satire of Vietnam movies, Tropic Thunder (2008), for example, Coogan’s nervy bluster and existential dread seems to both summon and justify his comic comeuppance—when a land mine turns him to mist.

But no one has put the 48-year-old Coogan’s Humpty Dumpty characters together better, or indeed set them on a higher wall, than his frequent collaborator, the director Michael Winterbottom. As the narcissistic storyteller (and as the narcissistic actor “Steve Coogan” playing him) in Winterbottom’s postmodernist Laurence Sterne adaptation of Tristram Shandy: A Cock & Bull Story (2006), and as the record label exec in the director’s electro-elegy 24 Hour Party People (2002), Coogan is sublime—as hilarious as he is heartbreaking. Along with Partridge and Coogan’s great, down-and-out ex-roadie, Tommy Saxondale, these characters were the best in the actor’s signature stable of hopelessly unaware assholes and neurotic martyrs. That is until Coogan, again at the behest of Winterbottom, climbed even higher up that cross to reach an even better character: himself.

Playing the semi-successful middle-aged actor “Steve Coogan,” alongside his frienemy “Rob Brydon” (played by Rob Brydon) in the road-foodie film The Trip (2011), Coogan is a postmodern puff pastry of irony, parody, and self-satire. It is the part he was truly born to play, so thank heavens he has reprised it, taking The Trip to Italy this month with all the original players.

In 2013, Coogan tried something new, co-writing, producing, and co-starring in Philomena, a serious drama about a woman’s search for her long lost son, for which he received two Oscar nominations (best picture and best adapted screenplay). Philomena‘s constant nemesis during the campaign season was the sci-fi epic Gravity, but along the red carpets and at those party tables, that film’s director, Alfonso Cuarón, and Coogan became good friends. The director called the actor to talk about the Amalfi Coast, the joys of aging, and determining your fate.

STEVE COOGAN: I feel really guilty about taking up your time for this.

ALFONSO CUARÓN: That’s a good thing. When I saw you last, I was professing my admiration. And maybe I was too over-enthusiastic, because I think you were a little uncomfortable.

COOGAN: I was a little bit. No, I couldn’t believe that you were so familiar with my stuff.

CUARÓN: Well, I’m glad you lifted my restraining order and now we can talk again. [Coogan laughs] I’m curious about Philomena, about why you decided to write a drama after years of doing all these comedies.

COOGAN: It was born out of a lot of things. One is that I was slightly frustrated as an actor being typecast because of Alan Partridge in the U.K. I thought, “I’m going to find my own project.” Also, I was bored of comedy for its own sake. I admire it, but I’ve done it for 20 years and it’s not enough. You want something that’s got more substance. I wasn’t going to write Philomena; I was just going to produce it and get a drama writer. But I kept telling Christine Langan at BBC how I would do the story, and she said, “Why don’t you just write it yourself?” She hooked me up with [screenwriter] Jeff Pope, and I sat down and thought, “Okay, I’ll have a go.”

CUARÓN: You wanted to write something for you to play?

COOGAN: Partly. It wasn’t entirely that. I was just fed up with not being the author of my own destiny. I just wanted to tell a story. I found the story in the newspaper. I thought, “Maybe I can be in this, or maybe I can produce it. Maybe I can direct it and put someone else in it.” I just wanted to do something—anything—that was different.

CUARÓN: You never thought of playing Philomena, right?

COOGAN: I never thought of playing Philomena. Well, someone did suggest it. And someone at the Golden Globes or something said they were going to write a movie for an older actor and they were also going to be in it. And Meryl Streep said, “Oh, you’re going to do a Coogan.” This is a cynical review of it—you’re going to do a Coogan—get a heavyweight actress, stick her in the lead role, and hang on to her coattails and maybe she can change the game for you a little bit.

CUARÓN: Now do you have to keep on doing it?

COOGAN: Well, the reason I did it is because I was a little fed up with ironic, postmodern filmmaking and entertainment. Everything seemed to be about the style, and it was starting to annoy me. I wanted to do something with genuine sentiment—not schmaltzy, just sincere. And for me, the best thing about Philomena is that people come up to me and say, “I watched it with my granddaughter, mom, and daughter.” Different generations all watch it and enjoy it. It was an exercise to show that you can be sincere and you don’t have to be self-important or sanctimonious. And so I figured, I want to talk about serious stuff and put comedy into it. Who knows, Alfonso? There might be something in it for you if you want to play your cards right. Where are you right now?

CUARÓN: In Italy.

COOGAN: Oh, I was there last week, on the Amalfi Coast, at that garden where John Huston shot Beat the Devil [1954]. You’re in a beautiful part of the world. But anyway, yes, I’m trying to develop movies that are about real people, and the Holy Grail is trying to do a movie that’s about something and makes people think, but is entertaining.

CUARÓN: Were you not tempted to do this before, when you were writing and playing all these characters?

COOGAN: I was doing what I was doing, and I was doing it pretty well. After Alan Partridge, I did the Saxondale character [in his BBC show Saxondale], and that’s a little more subtle than Partridge; it has more pathos and it’s a little more nuanced.

CUARÓN: I agree. I think I told you before, I love Saxondale. It’s just a very funny drama.

COOGAN: I think in the U.K. people judged it against Partridge, but weirdly, in the U.S. it’s got a kind of cult following. I think it’s because it was about a rebel, an outsider. Basically it was about the baby-boomer generation who are now directionless. The whole counterculture of the ’60s—those guys are getting old now and their authority figures are younger than they are. It always amused me: When the prime minister or the president has an electric guitar or likes rock music, then where’s the establishment? Where’s the “man” you’re supposed to rebel against? I always wondered how that older generation feels. Was it worth the fight? I like sad characters and damaged people. And Saxondale’s one of those guys.

CUARÓN: Saxondale and Partridge want to believe that they are something more extraordinary than what they are.

COOGAN: That’s true. And I think that might have something to do with me. I always think that, even when people behave badly, if you like something deep inside them, then there is a tiny bit of nobility—they wish they could be good.

CUARÓN: Now you play yourself, but you’re obviously playing a character that’s Steve Coogan.

COOGAN: What I didn’t want to do, because it’s been done very successfully, is be someone playing themselves as self satire—saying, “Get a load of me. I’m laughing at myself. I must be really cool.” It’s been done very well: Curb Your Enthusiasm; The Larry Sanders Show, in a way. I love Robert Altman movies when they have real people in them. I didn’t want it to be a gimmick. I told Michael [Winterbottom] I didn’t want to do it. How can people identify with it if it’s just me mocking my own ego? He said, “Well, it will resonate with people trying to find meaning in their life.” And I went, “Okay, I’ll trust you.” But what I like about it, when we did it properly, is that it’s like playing with fire. You use things about yourself and there’s a lot of improvisation. I wouldn’t always go for the laugh when I’m playing myself; I’ll go for the side of myself that is not funny and maybe slightly ugly, because it feels cathartic, and it feels like it will be interesting to go for something that we all have, that we try to edit. Because it’s our imperfections that make us vulnerable, make us interesting. How can I make myself a bit of an asshole and still have humanity about it?

CUARÓN: The first time I saw you doing that was in Coffee and Cigarettes [2004]. I don’t know if you had done it before.

COOGAN: I had never done it before, no. Jim [Jarmusch, the writer and director] had the idea, and then Alfred Molina, Jim, and I all talked about it on the phone. Jim said he wanted us to be cousins, and he wanted Alfred to be a little creepy. Between the three of us we came up with the idea of the balance of power shifting halfway through. And that’s always funny, when you see someone very naked. I’ve met people who’ve dismissed me, and then they find out that they like my work, and suddenly their attitude changes toward me. And I think that’s very funny and very human. But it’s also very unattractive.

CUARÓN: You played Steve Coogan in Cock & Bull, and now in The Trip, twice. Do you think Steve Coogan is consistent in each character?

COOGAN: I think it is. It’s everything I dislike about myself. In The Trip to Italy, I made myself less of a jerk—still self-absorbed, but trying to be a better person.

CUARÓN: Older.

COOGAN: It’s great, when you get middle-aged, you think, fuck. You want your work to mean something. You want to be successful, you want all the shiny things, but you want it to mean something. You’re halfway through your life, and you think, “One day I’m going to be dead. I want to talk about life and I want to talk about humanity.” Steve Coogan on the screen is slightly less noble. But I’m just as wrapped up in myself as I am when I play myself. But when I play myself, I want to be a slightly better person. It just agrees. Everything I play about myself is kind of true, but it’s amplified. We all edit, don’t we? If you’re self-aware, you stop yourself—you know how to behave properly.

CUARÓN: Rob Brydon is also playing Rob Brydon—I’m sure that he goes through the same process. But you two go way back.

COOGAN: I discovered him, and that sounds really, really pretentious, but I did. He sent me a videotape of his work. He was very, very good. He did some monologues for my company and we did them on the BBC, and then he did a TV series for me. And then he suddenly got this new career. And then he became very successful and turned on his creator, like Frankenstein.

CUARÓN: This is Steve Coogan the character talking, right?

COOGAN: Exactly. I love Rob, but this is what we do in The Trip. He does very mainstream stuff now; he’s very comfortable doing populist, popular TV shows. And I wouldn’t do the stuff he does. But we know that there is a little tension between us, so what we do is exploit it, press each other’s buttons. Really, all we’ve done is exaggerate. We make me a pretentious asshole—and there’s a little truth in that—and we make him the guy who will turn up to the opening of an envelope and do funny voices at any opportunity.

CUARÓN: And the screenplay is written by Michael Winterbottom?

COOGAN: Michael gives us a structure and then we improv within the structure.

CUARÓN: There is a big generosity between you and Rob. Not only the characters, because it’s clear that those characters love each other a lot, but also in terms of actors.

COOGAN: There’s that odd-couple thing where it’s just a game of swordsmanship. And he makes me laugh. If you were doing a more orthodox, Neil Simon script, you’d have toucher, parer, toucher, parer, like a fencing match.

But he says things that make me laugh, and so I’ll laugh, even when he annoys me. I think that’s very truthful. We are friends in reality, but not as tight as we are on screen.

CUARÓN: Okay, that’s interesting.

COOGAN: When we shoot The Trip, during the dinners, we deliberately prod each other a little bit to create some tension. The tension creates comedy. But in the evening, when we eat in reality, we get on very well, and we’re nice to each other.

CUARÓN: How does the improvising work?

COOGAN: Well, the first Trip was an exploration as much as it was a series. Rob and I were driving this Range Rover, and I was saying to him, “I would love to be in a costume drama with Michael Fassbender or Dominic West. I’d love to leap over walls with a sword and say things like, ‘Gentleman, to bed, for we rise at dawn.’ ” We started making each other laugh talking about this, but we kind of meant it. The second one was a little more disciplined because we couldn’t go around the locations a second time. We did a routine about Christian Bale and Tom Hardy doing Batman—laughing at them, but secretly we’d like to be them.

CUARÓN: Is this going to be some sort of Before Midnight series, with Steve and Rob—12 or 15 films with the two of you guys going on to your deaths?

COOGAN: Maybe. Part of me likes to be counterintuitive, so I go, “No, that’s a terrible idea.” And then I think, “Well, because it’s a terrible idea, it’s a good idea. We should do another one.” In The Trip to Italy, we talk about how as you get older, not as many women meet your eye when you look at them. I think Mike Nichols once said that he used to look at women, and then one day he woke up and women just looked straight through him like he wasn’t there. That whole cliché about laughter being the best medicine is very true. We’re all on this earth for so long, and we’re all going to die. And so the way to cope with that is to laugh. To laugh with growing old, to be self-effacing is really liberating.

CUARÓN: Are you writing something right now?

COOGAN: I’m writing another one with Jeff, something different, semi-autobiographical. It’s a little ambitious, about childhood. I think Europeans—when I say Europeans, I mean everyone except the British and the Americans [laughs]—the rest of Europe is very comfortable with making movies about childhood. We don’t do it so much.

CUARÓN: I liked Submarine [written and directed by Richard Ayoade, 2011].

COOGAN: Oh, that’s absolutely right, I did like Submarine a lot. That had wit and it was also contemplative. It was introspective and interesting. And that’s what I’d like to do, make movies about real people. The thing about comedy is, if it’s supposed to be funny and they’re not laughing, it doesn’t work. That’s what’s brutal about it. And that’s what’s fun about it as well. If there’s a subtext to it, that’s a bonus, but that’s down the list of priorities. And shedding light on the human condition is right there at the bottom of the list. Whereas when you’re doing a Philomena, that was right there at the top of the list. I like comedy, but I like comedy as a device in drama. It’s more interesting for me to use comedy to seduce people into thinking about something serious. If you want to hit a beat in a drama, you can distract people with a little comedy, and you can punch them in the gut with some emotion.

CUARÓN: You’ll keep on doing both, right?

COOGAN: I’ll do more drama but I will still go back to Alan. I’d also quite like to go back to Saxondale.

CUARÓN: Do you ever dream as your characters?

COOGAN: No, I don’t dream.

CUARÓN: Never?

COOGAN: I don’t dream that I am my characters. I do think of them as other people. I always talk about Alan in the third person. And when I watch myself doing Alan Partridge, I laugh, because I don’t see me. I see someone else. I’m assuming that’s kind of strange. Armando Iannucci and Patrick Marber, who’s a screenwriter now, invented Partridge with me more than 20 years ago. When you look at 20 years ago, it’s quite crude, but as an audience becomes familiar with a character, you can be more nuanced and darker and go more into his head, and they will go right with you. If I were only doing Alan, I think I’d have some existential crisis. But because I’m able to do these other things, it makes it more likely that I’ll go back and do comedy because I don’t feel like I’m trapped, I feel like I’m doing it because I want to.

CUARÓN: If Alan interviewed Saxondale, would they get along?

COOGAN: No, I think Saxondale would think Alan’s a dick. Saxondale would think Alan is an ass-kissing member of the establishment. Saxondale likes to think he’s a rebel, that he’s a maverick, a lone wolf. And he would think Partridge is too cheesy. Alan Partridge would like to be an OBE [Order of the British Empire] or get a New Year Honour from the queen.

CUARÓN: And what about you? Do you want to be an OBE?

COOGAN: No, I don’t believe in all that. Well, I just kind of nailed my course to the mast. I’d like to be offered one. If you look at the list of people who’ve turned them down, it’s always cool.

CUARÓN: It’s a really cool group of people. And what about the childhood one you’re writing, is that something for you to act in?

COOGAN: I think if you try to look for something to show off as an actor, vanity can get the better of you.

CUARÓN: You’re writing it, are you thinking to direct it as well?

COOGAN: Maybe. If I directed it, I wouldn’t be in it. I like working with people who let me have an opinion. I think I’m good with actors. I like directing actors. I also like to show up and just do an acting gig. Where I’m just a hired gun, I don’t have to have an opinion on anything. I never got involved in all this stuff because I wanted to control stuff; I got involved in writing and producing because I wasn’t getting interesting acting gigs. In a way I’m grateful that I didn’t get interesting roles, because it made me pull my finger out and do some work. The funny thing is, Alfonso, when I used to go to L.A. and do this little job or that little job, nothing really happened to me the way I wanted it to. And then when I came back to England and started doing my own thing, doing what I knew that I wanted to do, and not trying to say, “Hire me, put me in your movie,” then things started happening for me.

CUARÓN: You should have not worn that Catwoman suit.

COOGAN: [laughs] You know when I did Pauline Calf [a character of Coogan’s, Pauline is sister to Paul Calf, also played by Coogan] I had prosthetic breasts made for myself. And they cost more than a real boob job. I got a series of e-mails from the guy who made them and all the prosthetic limbs for Saving Private Ryan [1998]. It’s the most hilarious chain of e-mails, asking, “How would you like the breasts? Fuller, higher? Would you like them to hang slightly? Do you want them to be a little pendulous? Do you want them to be firm? What kind of nipple would you like?” They made two sets for me. I’ve still got them somewhere.

ALFONSO CUAROÌN IS A SCREENWRITER, PRODUCER, EDITOR, AND THE DIRECTOR OF Y TU MAMAÌ TAMBIEÌN, CHILDREN OF MEN, AND GRAVITY, THE LATTER FOR WHICH HE WON TWO ACADEMY AWARDS.