Sissy By Andy

This story is part of a collection celebrating the best—and wildest—Warhol conversations from the Interview archives.

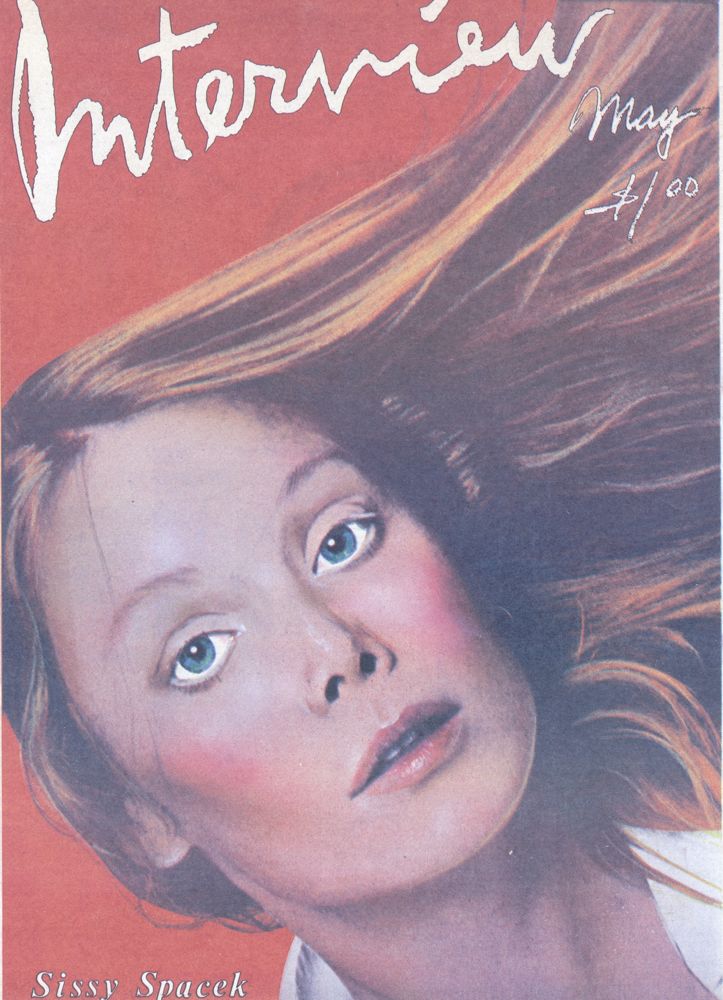

Andy Warhol and Bob Colacello arrived at the Sherry Netherlands in April 1977 at the suite of Sissy Spacek, star of Carrie and Three Women. Sissy is waiting there with her mother, who excuses herself and disappears into the bedroom, and Neil Konigsberg, a Hollywood press agent, who calls room service for Coca-Colas. Sissy is wearing a black, wool gabardine, man-tailored pantsuit, a blue and white check, cotton shirt, and no makeup.

———

ANDY WARHOL: I brought you a copy of my book.

SISSY SPACEK: Would you sign it?

WARHOL: I already have. We were arguing how to spell your name. Bob thought it was S-I-S-S-Y.

SPACEK: He’s right. I changed it. But then I changed it back.

WARHOL: Then I was wondering why you were called Sissy.

SPACEK: Two brothers. My real name is Mary-Elizabeth.

WARHOL: I thought only boys were called sissies.

SPACEK: That’s big in Texas—Sissy with an “s”. I’ve known about three or four other Sissys and they’ve all been from Texas.

BOB COLACELLO: What part of Texas are you from?

SPACEK: The Northeast, the Big Woods, near Tyler and Longview.

COLACELLO: What was your childhood like?

SPACEK: Great. I didn’t have a lot of competition there. I rode horses a lot, was in rodeos, twirled the baton and did all things that a young Southern girl’s supposed to do.

COLACELLO: Was it a small town?

SPACEK: Real small—1,237 people. It’s called Quitman. I have a house there now about five miles out of town.

WARHOL: How do you get from there to Hollywood?

SPACEK: Just about every town in Texas has a beauty pageant. Ours was called The Dogwood Fiesta. I was in one of those. I played the guitar and sang—and lost. But one of the judges was a newspaper reporter and she was going to New York and my brother was real sick at the time and my parents thought it would be good for me to get out from under that so I came to visit. I stayed with Rip (Torn) and Geraldine (Page) for about a month and a half.

COLACELLO: That’s right, you’re related to Rip.

WARHOL: You mean your name could have been Sissy Torn?

SPACEK: No, it couldn’t have been. My father and Rip’s mother are brother and sister. Her name was Spacek.

COLACELLO: What kind of name is that?

SPACEK: Czech.

WARHOL: Really?

COLACELLO: Andy’s Czech.

SPACEK: Really? I just got a letter from there. I’m beginning to hear from Spaceks all over the world.

COLACELLO: How do people from your hometown feel about your stardom?

SPACEK: I go back there a lot and they think it’s real neat. You know how you get blasé but they make it exciting again, especially if I’m in a magazine that’s in a grocery store. It’s great but it doesn’t make that much difference. They always thought I was special—or affected, whichever the case may be.

WARHOL: I voted for you to win the Academy Awards at a party in Hollywood.

SPACEK: Everybody I talked to voted for me. I don’t know what happened! Did you go to the Awards?

WARHOL: No, I think it’s better on television.

SPACKEK: And I was sitting in the front row. Practically the whole excitement is seein’ all those people in the flesh and I couldn’t see anybody. Of course, I couldn’t wear my glasses because they didn’t go with my dress.

WARHOL: I met your co-star in Hollywood—William Katt. He’s great.

SPACEK: Isn’t he? I get fan letters saying, “You were great. Can you get me in touch with Billy Kat.”

COLACELLO: Where do you live now? In Los Angeles?

SPACEK: Yes, in Topanga Canyon. My husband and I have lived there for about five years.

WARHOL: How did your family get to Texas from Czechoslovakia?

SPACEK: It wasn’t easy. I think my mother’s family came on the Mayflower from England—D.A.R., you know. My father’s family is German and Czech. They settled in central Texas where Rip grew up. They’ve been there, I think, two generations or three. I remember the town my grandmother lived in was all Czech. By then we moved, from the time I can remember, to Northeast Texas, which is very rural with a lot of Arkansas and Louisiana influence. I’ve read that it’s the least defined area of Texas.

COLACELLO: How long have you been married?

SPACEK: About three years.

COLACELLO: What does your husband do?

SPACEK: He’s a real fine set designer. We met on Badlands.

COLACELLO: I loved that one. How many films have you done?

SPACEK: Altogether? About six.

COLACELLO: How old are you?

SPACEK: Twenty-seven.

COLACELLO: But in Carrie you play someone really young.

SPACEK: I’ve been real lucky. Because I look real young I’ve been able to do parts of different ages. I don’t know if it’s broader range because I haven’t been able to play my own age very often. But it’s gettin’ harder and harder to remember what it was like to be 16 years old.

COLACELLO: What do you do when you’re not working?

SPACEK: I like horseback riding, I like to hike, I play guitar and sing. Recently I’ve been spendin’ a lot of time in Texas, in the woods, havin’ revelations. And in between acting jobs I’ve been doing set decorating. That’s how I met Brian De Palma as well as my husband Jack Fisk.

COLACELLO: Aren’t you competing with your husband for set-decorating jobs, then?

SPACEK: No, ’cause he’s the boss. Aesthetically and creatively we work real well together.

WARHOL: I think the designer makes the movie.

SPACEK: People don’t realize how much a designer does. It’s incredible. And us workin’ together with a director is a triangle and there’s somethin’ really extra. As you have ideas about a scene, or have a particular idea about one aspect of a character, the set can be designed to suit that. For Carrie that made an incredible difference. Jack worked on that. In fact, it’s hard for me now when we don’t work together.

COLACELLO: Do you like to travel?

SPACEK: Yes, but I find that creatively you have to change gears and that can throw you off. I’ve gotten a pretty good balance, though, between Texas, Los Angeles and here. I lived here, you know, for six years, startin’ in ’67.

WARHOL: Did you work here?

SPACEK: Yes, I was in the music business. You know, I sang on the soundtrack for Lonesome Cowboys. And I was extra in that film Holly Woodlawn did—Trash. That was my first film. It was a bar scene.

WARHOL: Gee. How did that happen?

SPACEK: I think I met Holly with some other people at this place down on 17th Street—Max’s Kansas City.

WARHOL: You used to hang out there?

SPACEK: Oh, goodness yes. It was on my way home from acting school. This gets sort of foggy. I lose whole sections of the past.

WARHOL: What made you move out to California?

SPACEK: I worked on a film, Prime Cut, in Canada. And everybody felt broke up housekeepin’ and all went out to California. I went back to New York and felt real out of it. Then I went out to test for another film and just stayed. Gradually, over a period of about a year, I moved my stuff out to Los Angeles, one suitcase at a time.

WARHOL: Hollywood’s so strange. It seems like no one is working out there but they must be.

SPACEK: It does seem that way. You get into a good life out there.

WARHOL: Are you doing another movie now?

SPACEK: I’m goin’ to be startin’ one soon with Nicholas Roeg. It doesn’t have a name yet but Art Garfunkel and I are goin’ to be in it and we’re goin’ to do it in Vienna. It’s sort of a mystery-romance.

WARHOL: Do you have a dream role?

SPACEK: No. I guess I should dream one up. And Three Women is sort of a dream. It’s a very odd mood piece. I like Bob Altman because he becomes himself real far out on a limb all of the time. I’d like to direct pictures. I’ve only really been working for a year and I’ve worked with really great directors. I’d like to work with other great directors and absorb things. I worked with the directors of what they call the New Hollywood and it’s been great because most of my training has been while I work. But I see that film is a director’s medium and each director perceives reality in his own peculiar way. I would really like to direct.

WARHOL: It’s funny they never write about you in the scandal sheets. I guess it’s because you always play such a young person.

SPACEK: I’m grouped together with Tatum O’Neal and Jodie Foster. That’s fine with me. You see, you can get by with a lot more that way. People let things slide. That’s good, I guess.

WARHOL: And child actors are getting so big again.

SPACEK: I wonder why.

COLACELLO: I think because everything’s going in an escapist direction because things are getting worse.

SPACEK: Do you think so?

COLACELLO: They don’t seem to be getting better. The news magazines always used to have hard news stories on the covers. Now it’s entertainment stories.

SPACEK: I see you—you get overloaded by the truth. That’s the nice thing about livin’ in Los Angeles. Anything that happens in the news—great tragedies, scandals—people just think, “What a great idea for a film!” Everything’s thought of in terms of “material.” Remember that thing in Uganda? They couldn’t get the films out fast enough.

WARHOL: Do you ever get nervous?

SPACEK: I did a little when I did Saturday Night Live a few weeks ago. The stage manager was runnin’ me through all this dangerous stage equipment real fast and all the costume changes and sets. But I loved the perspective from the back when you’re goin’ through the sets and seein’ all the cracks. It’s so incredible. Gosh! I loved it. I’d never worked with three cameras before, live. It was Thursday evening before I found out what sketch reality was—no reality-reality but sketch reality.

WARHOL: What is it?

SPACEK: In a film, you’re playin’ eye to eye, like we’re doin’ right here. If you’re doin’ three cameras live, you’re usin’ cue-cards, so they’re three cameras there and you’re playin’ more like on a stage, I guess. Instead of us eyeballin’ each other, we’re playin’ the cameras in the audience.

WARHOL: And that’s what sketch-reality is?

SPACEK: I’m still not sure! I did one sketch where I had to do a Southern accent. I don’t mean my real Southern accent. I mean a put on Southern accent. I loved doin’ that.

WARHOL: I think you’d be great in Tennessee Williams’ plays.

SPACEK: His work is so pure. You know, it’s so hard, workin’ in films you… that’s the thing I like about Terry Malick’s writing in Badlands. The rhythm of the words, besides the meaning, just makes your tongue feel so good when you say it. It goes beyond the thought, even. You very seldom hear this, especially in films. I guess I’m especially sensitive to this, comin’ from the South.

I think that it must be a difficult position to be in for a little kid-getting’ eyeballed at all times. You know there’s always aunts and uncles who think you should be this way or that way but here’s a whole country doin’ that.

WARHOL: You’re really locked in.

SPACEK: But it’s so amazing how many different things an individual can project and what different things different people can see in different ways. I love that.

WARHOL: Ten people can take a picture of you all at once and they come out completely different.

SPACEK: And you know what? It almost gets to a point, if you’re talented, where it doesn’t really matter how other people perceive you. They just see whatever they want to see. You become…

WARHOL: Oh, I know.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE MAY 1977 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

———

Read more stories from the Celebrating Warhol collection.