Sini Andersonâ??s Girl At The Front

The trademark siren howl of Kathleen Hanna, front woman of seminal riot grrrl band Bikini Kill, electro-pop act Le Tigre, and now, the Julie Ruin, has served as a totem of a certain kind of political consciousness and female liberation: inclusive, accessible, and a force to be reckoned with. Hanna, who emerged (however reluctantly) in the ’90s as the de facto face of riot grrrl and what would come to be recognized as third wave feminism, has long leant her voice to others, and she hasn’t let up.

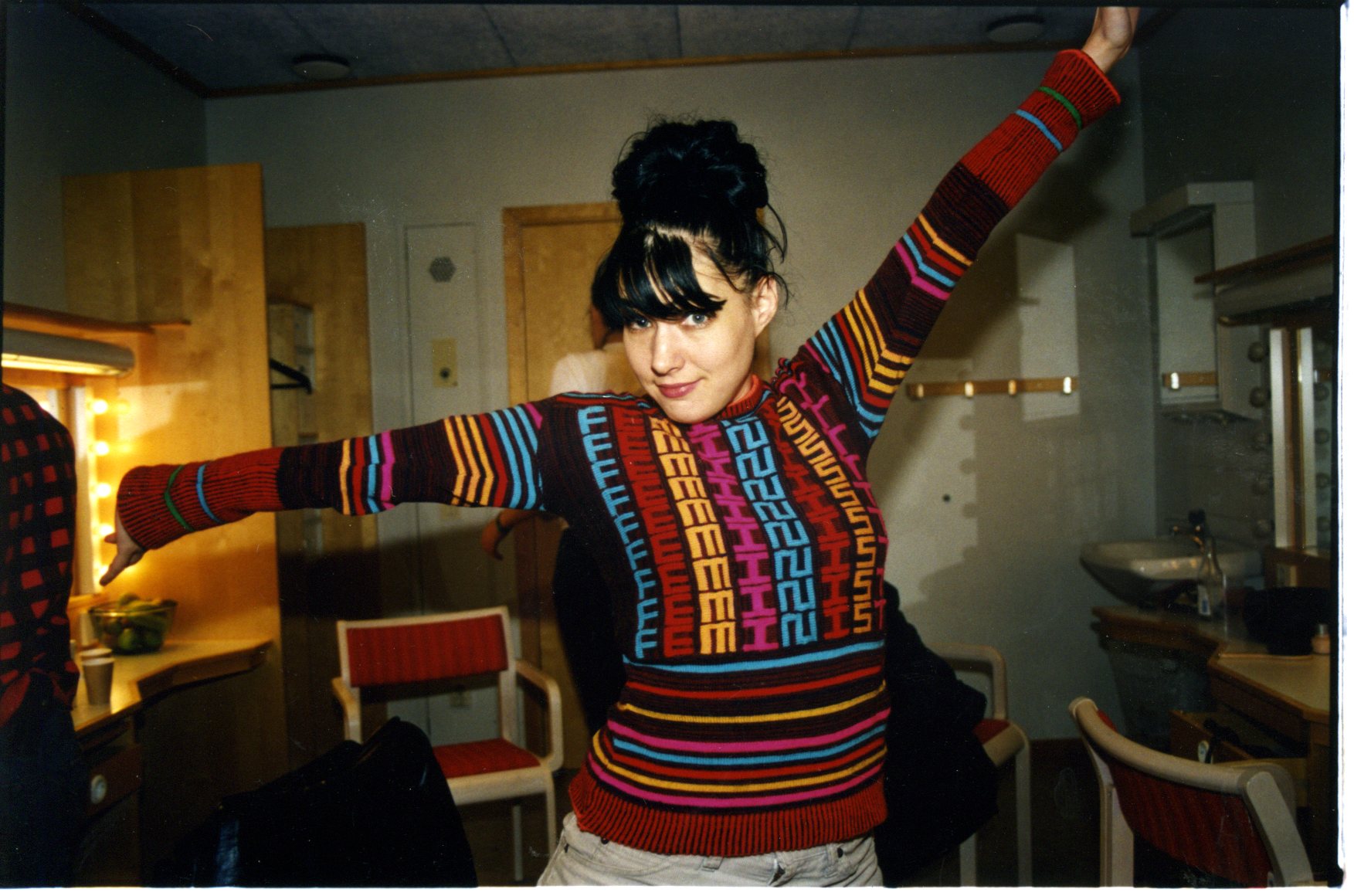

Now 45, Hanna serves as the subject of performance poet, producer, and director Sini Anderson’s debut documentary, The Punk Singer, executive produced by Tamra Davis. Tracking Hanna’s life from her childhood in the Pacific Northwest through her journey with riot grrrl, marriage to Beastie Boy Adam Horovitz, and subsequent withdrawal from the public eye due to a battle with late-stage Lyme disease, the film, told through 20 years of archival footage and a series of interviews featuring Kim Gordon, Sleater-Kinney’s Corin Tucker and Carrie Brownstein, Joan Jett, JD Samson, and Jennifer Baumgardner, emerges as both an intimate and invigorating portrait of Hanna, her work, and her ever-evolving status as an unstoppable cultural icon.

Interview recently caught up with Anderson in New York.

COLLEEN KELSEY: One of the things I found to be compelling about the film right off the bat was the title, especially since punk is, to a certain extent, kind of a boys’ club. Why did you choose that title and how does Kathleen align with it?

SINI ANDERSON: Well, I loved the idea of making such a bold statement. It’s also a song, right? It’s a song that she wrote on the Julie Ruin [Hanna’s 1997 solo] album. And I did love that we were calling it The Punk Singer—we’re calling her “the punk singer“ and not just “punk singer.” It felt like claiming space.

KELSEY: How did you first meet Kathleen and get started on this project?

ANDERSON: We met in 2000 at a women’s music festival. We were both on the same label, Mr. Lady Records. We had known about each other but we hadn’t actually met. We finally met through our mutual friend [artist] Tammy Rae Carland, who ran Mr. Lady Records. And we just hit it off, kind of, right away—we’re both Scorpios, both the same age, same kind of interests.

KELSEY: How open was she in making a film about herself?

ANDERSON: I think she was really nervous about it. You know, Kathleen’s one of these artists that does a great job of putting the people that she works with in front of her and not taking all the credit. So, for the focus to purely be on her, I think, made her a little uncomfortable. But, I also feel like she heard me when I said, “People need to hear your story.” And once it was put to her in that way, this could be a service to a lot of people and we need that inspiration right now, she was willing to step up and be like, “Okay. I’ll do it.”

KELSEY: How did you go about meshing Kathleen’s personal narrative with the larger movement that surrounded her, because the film puts Kathleen at the center of riot grrrl’s social and political context, but still fleshes out the movement at large.

ANDERSON: I don’t think that that, in this case, is so much of a challenge. One of the sayings in the ’90s was, “The personal is political.” Her personality and her experiences are not that separate from her art; they’re really intertwined. So, it would be impossible to tell the story of riot grrrl without telling part of Kathleen’s personal story. And it would be impossible to tell the story of Bikini Kill without there being a personal narrative of Kathleen’s life in there. She’s one of these artists that, she writes an amazing pop song, but she also does a really great job of putting her personal experience and her life out there in her art. So, there is no separating the movement from the person, in a lot of ways.

KELSEY: The sociopolitical climate of the early ’90s influenced Kathleen and her peers in terms of rehashing the conversation of, “Is feminism dead? What does feminism mean to you? Are you feeling connected or disconnected from women a generation before you or not?” People are having a lot of the same conversations right now.

ANDERSON: Yeah. That’s what we do—things go in waves. When you have a really personal connection, an inherent connection, like: I’m a queer feminist—I have an inherent connection to feminists and to queers that have come before me. I feel like when you’re just discovering that there’s a lot of push back in the movement that maybe came before you, it’s just something that happens. As you get a little bit older, you see what you are repeating. I see a lot of what we were doing with third-wave feminism and second-wave feminism. One of my favorite parts of the film is the conversation between Kathleen and Gloria Steinem. Those conversations are amazing. I wonder who is performing now that’s going to have the conversation with Kathleen. I think we are in a new wave right now. But I also see younger feminists being really, really open to Kathleen in a way that we, when we were in our early 20s, didn’t have that many role models. Or, they were hard to find. Feminists are usually hard to find in history.

KELSEY: Kathleen is so open about pushing for the visibility of female artists and for pointing out the fact that society is not so open to women calling out society or the media when something is sexist or ignorant. The film felt very timely in terms of younger women in the media, like the Mindy Kalings or the Diablo Codys or the Lena Dunhams, who have been quite vocal about similar circumstances today.

ANDERSON: Absolutely. One of the goals of the film was to take some of the personal experiences that are unique to women and make them more public. There’s so much isolation that happens with our personal experiences and personal shame that’s connected to that; the more that breathes, the more inspiring it becomes for people to open up about those types of things. And then that creates energy and energy creates movements. There’s nothing that’s going to change if we are without energy, in isolation, or in shame about personal experiences. We’re not even starting from zero, at that point—it’s negative. The really great thing that Kathleen does, and the other artists that you mentioned, is to say, “Hey, you’re not a freak. A lot of us are experiencing this.” And then when we hear other people talk about that, it gives us energy to really start concentrating on the art that we want to make.

KELSEY: In the film, Kathleen makes a correlation between pushing for the visibility of female artists and pushing for the visibility of her illness, which turns out to be late-stage Lyme disease. Was she diagnosed when you were filming?

ANDERSON: She was diagnosed about halfway through the production. When we started, she was battling this illness and it was coming and going. She looks beautiful and totally fine in the film. But then another flare would come on and we didn’t have access to her for a while. The diagnosis came about halfway through the film, and then I started learning a little bit more about it. That’s really the thread that I saw at the end of the day. I feel like we do a pretty successful job of showing at the end of the film, the thread that goes all the way through, is standing up and talking about the thing that people don’t want you to talk about. So, where she’s at in her life right now, it happens to be this disease. And, of course, Kathleen Hanna happens to get this really devastating and political disease that a lot of the medical establishment is saying doesn’t exist. And, you know, that’s really similar to people turning their head away at sexual abuse survivors, and saying that’s not happening. So, it’s no mistake. Here she is again, stepping forward and saying, “Hey, I know that you guys think this is bullshit, but it’s not.” We need that. We need people stepping forward and calling that out.

KELSEY: Kathleen has been such a pioneer for women in music and women artists. Is there anyone now that you see from the younger generation that’s continuing her legacy?

ANDERSON: Well, I think Lena Dunham is doing a really amazing job. I’m a huge fan of hers. Mostly when we see young women who are putting themselves out there and their work being trashed in the media, all that does for me is make me a huge fan of theirs. Because I’m just like, “Oh, my god. Here we go again.” I don’t know who the next Kathleen Hanna is. I don’t think there is one. She’s mid-career and still making really important work. I can’t wait to see what she’s going to do in the future. But, I do see younger women artists being more comfortable with their power than they have been in the past and being encouraged to be in that power. And I think that’s a direct result of a lot of what happened in third-wave feminism.

KELSEY: A lot of people still have apprehension when it comes to the word feminist—or branding oneself as a feminist. I recently was reading an article where some pop singer said, “I’m for women, but I’m not a feminist.”

ANDERSON: I feel like we all want to be accepted and loved, and not judged. I think that there’s a lot of fear associated with the word feminist and I think it comes from people who actually—and no fault, I mean, I’m not trying to shame or blame them—really don’t know what the definition of a feminist is. And I think, quite frankly, people—like I said—they want to be accepted, they want to be loved, they don’t want to be judged. A lot of people don’t want to be perceived to be a man-hating lesbian. [laughs] We’re still living in that. Sometimes it just boils down to education. And I say that as someone who’s not traditionally educated. I didn’t go to high school. I didn’t go to college. Everything I learned, I learned through my own community. But I think people aren’t really being presented with the true definition of what feminism is. We’re putting these fashion tags on it, and we’re putting these judgments on it, and really it’s just almost laughable at this point when people are like, “Um, no. I’m not a feminist.” It’s just like, “What? I don’t understand.” That’s totally fine—they don’t have to identify that way—but it’s kind of hilarious that people still associate feminism with man-hating and sexual identity. It’s kind of hilarious that sexual identity could be something that people are so afraid of.

THE PUNK SINGER OPENS IN LIMITED RELEASE THIS FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 29.